Flash News

Flash News

AMP checks at Kapshtica customs, drug found hidden in a vehicle

Insult and denigration, the Journalists Association of Albania condemns Ristan's attack on the "Piranha" journalist

"Land Rover" abandoned for two years in the Port of Durres, 3 firearms and cartridges found, 24-year-old wanted

Mavraj's message to the Rossoneri: Kosovo is ours forever. Now play football

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

Bloomberg analyzes Tirana / A denser city, but at what cost? (And construction invites money laundering)

Albania's capital is getting a makeover intended to stop urban sprawl. But critics say the plan could leave Tirana changed beyond recognition, and erase its history.

Jessica Bateman

Over the next decade, Tirana is poised for a dramatic makeover. In the center of the Albanian capital, modern high-rises are taking the place of the current mix of informally constructed and historic buildings, under a plan called Tirana 2030. The government says its aim is to stop urban sprawl by concentrating construction in the city core, and to turn Tirana into a greener city with bike lanes, more electric vehicles and forested areas encircling the center.

Albania remains one of Europe's poorest countries, with a per capita GDP that's around 30% of the European Union average. And according to the city, the dramatic reboot is needed to turn Albania's vibrant but chaotic capital into a modern European metropolis. "Tirana is a city that grows by about 30,000 people a year, [so the question is] how to plan this growth in a sustainable way," says Mayor Erion Veliaj, a member of the governing Socialist Party. "I think we broke the myth that only rich cities could do this."

But with skyscrapers mushrooming across the city and some key historic buildings already demolished, critics of the plan worry their city is being sold out to developers with little public consultation, in a process that could leave their home changed beyond recognition. Architects, academics and activists say the demolition is leading to a loss of history, increasing housing prices - and possibly even functioning as a money-laundering operation for organized crime.

"When you look at the plans, you see that the whole city is in development," says Doriana Musai, an architect who took part in protests.

Albania's rich history is on full display in Tirana's city center. Skanderbeg Square, the vast plaza at its heart, became the designated center of the city after liberation from the Ottoman Empire in the early 1900s. Designed during the Italian occupation, it contains both 1930s Italian Modernist buildings and Soviet-style architecture from the later socialist period. Farther out, broad avenues feature an eclectic mix of Italian-era tenements and later apartment blocks - many of them radically remodeled by their occupants since the fall of communism in the early 1990s. Smaller village-like streets intersect, creating a haphazard but vibrant urban patchwork.

Skanderbeg Square is now at the center of the city changes. Previously one of the busiest roundabouts in the city, it has been pedestrianized, creating much-needed public space. But there are also some more controversial additions: At least four high rises, in various states of construction, have popped up over the past two years. What is missing is also striking. South of this cluster, there's a hole where one landmark once stood. Albania's National Theater, constructed in 1938 and considered an exceptional example of Italian futurism, was demolished in May 2020 following a two-year occupation by activists, to make way for a newer, larger theater. When the demolition took place late at night, unannounced, many activists were still inside. Following the protests, architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group was reported to have pulled out of the project, drawing work to a standstill and leaving the site unused and blocked by temporary fencing, with a candle-filled mini-shrine to the old theater in front. Ingels did not respond to CityLab's request for comment.

"Everything is at risk… our collective memory, our heritage sites," said Musai, who protested at the theater. “And it is stimulating gentrification. The new city is taking over everything and we cannot allow this, because we will lose connection with our past. ”

Plans for overhauling the city center were first revealed in 2016 under the name Tirana 2030. Joni Baboci, an advisor to the mayor on planning and architecture, says the aim was to "reimagine territorial Tirana." Since the former communist regime fell in the early 1990s, thousands of people moved from rural areas to the capital in search of work, building settlements on former state-owned agricultural land. Baboci argues that, although this gave the city plenty of character, it resulted in a lack of public space and no architectural harmony.

"We wanted to create a small, very dense urban center and preserve as much as possible of the suburban and rural territory," he explains. "So the plan pretty much forbids development for residential reasons outside of the core, and incentivizes people to build in the center." Italian architect Stefano Boeri designed an orbital forest to enclose this center, and helped devise a city plan that would ensure more greenery and public space. Bike lanes have been introduced, as well as incentives for taxi drivers to switch to electric cars.

According to Baboci, developers are encouraged to build higher in order to increase density. In return, they must give a certain percentage of land around the building to the city to use as public space. The higher they build, the larger the proportion is that must go back to the city. Some flexibility is allowed with story height, although Baboci says they are aiming for similarities in style and color scheme. To make way for this new construction, existing buildings are being demolished. Baboci says property developers usually enter into an agreement with current landowners, who are gifted a percentage of the finished development. The municipality also collects an 8% tax, and Baboci says the decision to concentrate development in the center was partly financially motivated, as property prices are higher there.

It's easy to see the appeal for a cash-strapped local government in raising funds and developing public space. The haphazard development of Tirana has meant that facilities such as playgrounds and parks have been scarce. But critics say that the developments taking place so far do not meet its own criteria, such as donating some of the land for public space, and that many are being built without any clear plan.

"A zone might say that 5% of land must be public, but it does not say exactly where this will be or what it will look like," says Musai. “There is zero transparency. We've put a lot of questions to the municipality and to the government and they either don't respond to us or, if they do, they don't actually answer our questions. "

In response, Veliaj says that every building permit issued so far has seen a sizable share of ground land given back for public use, and says he is happy to answer questions if people have concerns about specific projects. "We've done 27 official consultations in every borough," he says. “When you say 'not in my backyard,' you first have to answer, is it really your backyard? … If this is not your actual backyard, and if this is actually providing employment and freeing public spaces, then I really think those who complain should attend consultations. ”

The municipality also says that the plans are online for all to see - a map on its website lists what can be built in each small “zone” of the city center in terms of height and land use, and extensive PDFs of the plans have also been published. Boeri has also shared his own renderings showing many of the green features of the new design. But no detailed plan of exactly what the transformed center will look like has been published. Activists and architects argue this makes it impossible for ordinary people to understand what form developments will take.

Given the country's weak economy, there are also concerns over where the money for these developments is coming from. According to a number of experts, the country has become a favorite spot for international criminals to clean their money. Anti-mafia prosecutors in Italy found that the Ndrangheta crime syndicate had identified Tirana's new construction as a laundering opportunity. The Financial Action Task Force (FAFT), a global money laundering watchdog, has put Albania on its “gray list,” meaning it is considered high risk for money laundering due to weaknesses in its systems, and has earmarked real estate as a sector of particular concern. And Albania's Office of the General Directorate for the Prevention of Money Laundering says that it observed “considerable real estate investments with unknown source of funds,

But Baboci does not believe illicit activity is widespread. "In my opinion, when you're building, it's not easy to launder money," he says. "Anyone can go check and see what you have invested and how much you have declared."

Albania made a political commitment to strengthen its anti-laundering systems in February 2020, and has taken steps since, including an increase in targeted financial sanctions. Veliaj adds: "We have a money laundering agency that checks all the finances. Everything gets paid through the bank. Unlike the previous administration, where people came with wads of cash to pay their tax, it is done completely online. The permits are given online. ”

No matter the source of the money, the rise in real estate prices is making housing less affordable. Tirana property prices rose by about 6% since 2020, while the overall economy shrank by almost the same amount due to the pandemic.

The Municipality of Tirana says that any building listed as a monument of culture will not be demolished, and has pointed to the fact that the National Theater was never listed as an explanation for its destruction. But this misses the point, according to Paolo Vitti, a professor of architecture at the University of Notre Dame and a board member of Europa Nostra, a cultural heritage NGO that spoke out against theater destruction. He argues that the entire center of Tirana should be protected due to both its history and architectural importance.

"Over the past ten years there has been a very aggressive attitude by the municipality in trying to sell the idea that modernity comes from tearing down old buildings and creating spectacular contemporary architecture," he says, adding that the new construction does not complement the historic core.

He also warns that this type of top-down development, which he argues essentially imports an anonymous-feeling new city on top of an existing one, risks creating a host of environmental and social problems, including alienation and civil unrest. "Buildings are only meaningful if people ascribe meaning to them," he says. "They do not exist for their objective value."

Although the occupation of the theater helped build a visible civil society movement, most activists do not believe it is strong enough to stop the ongoing development. The ruling Socialist Party, which took power in 2013, recently won a third term, giving them a mandate to push ahead with their plans. "We have been searching for justice and we have done everything in our power as citizens," says Musai. "They want to impose their will, and the public is being excluded from decision-making. Our laws are not enough to protect our heritage. It is being destroyed and replaced with a new model. ”

Latest news

Kosovo Assembly fails to be constituted even after 28 attempts

2025-06-07 11:58:58

Oh Albania, you have no old age!

2025-06-07 11:05:01

Mavraj's message to the Rossoneri: Kosovo is ours forever. Now play football

2025-06-07 10:10:52

Why are Ukrainians being accused of arson at Keir Starmer's properties?

2025-06-07 09:16:24

Foreign exchange, how much foreign currencies are sold and bought today

2025-06-07 09:04:55

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-07 08:31:29

Weather forecast for Saturday, here's what the temperatures will be like

2025-06-07 08:17:35

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

2025-06-07 08:01:23

Heavy metals in the Drin River, causes of cancerous diseases

2025-06-06 22:54:02

Works in Spaç, Lubonja: Destruction of collective and historical memory

2025-06-06 21:54:32

DASH: Balkans, part of American strategy for expelling migrants

2025-06-06 21:12:33

Ilir Shqina, a diplomat, and her business partner Grida Dumas were suddenly born

2025-06-06 20:21:46

Couple injured in Kavaja, police find firearm hidden in wall

2025-06-06 19:05:19

EULEX mandate in Kosovo extended until 2027

2025-06-06 17:58:20

These are the 3 zodiac signs that will be favored in the next decade

2025-06-06 17:50:52

Anthropology

2025-06-06 17:06:00

EU supports International Criminal Court after US sanctions

2025-06-06 16:47:51

Gonxhe ignores concerns about Spaçi and defends the continuation of the works

2025-06-06 16:31:42

Providing online services, report: Institutions, delays in update requests

2025-06-06 16:24:10

The head of the Vlora Cadastre is changed again

2025-06-06 15:58:49

With a rounded belly, Dafina Zeqiri enjoys the holidays with her partner

2025-06-06 15:36:06

Foods that should not be missing from the Eid al-Adha table

2025-06-06 15:04:48

They exploited girls for prostitution in Vlora, 28-year-old arrested

2025-06-06 14:44:26

Israel warns of more attacks in Lebanon

2025-06-06 14:26:30

The race for the head of the BKH, the deadline for applications ends today

2025-06-06 14:15:18

14-year-old girl in Vlora rescued after risking drowning at sea

2025-06-06 14:04:23

Challenge with Albania, Serbian team arrives in Tirana

2025-06-06 13:49:04

He injured the married couple in Rrogozhina, here is who the perpetrator is

2025-06-06 13:34:20

Berisha wishes Eid al-Adha: Blessings to your families and our nation

2025-06-06 13:09:28

He injured his neighbors with a gun, the perpetrator surrendered to the police

2025-06-06 13:02:47

Tom Cruise enters Guinness World Records

2025-06-06 12:38:48

From orange peels to bananas, discover the foods that help you with stress

2025-06-06 12:28:53

How did the feud between Donald Trump and Elon Musk start?

2025-06-06 11:52:32

The prosecution sends 5 Kosovar citizens to trial for drug smuggling

2025-06-06 11:33:56

21-year-old injured with knife in Saranda

2025-06-06 11:24:10

Kosovo citizens flock to the Albanian coast, long queue from Morina

2025-06-06 11:11:07

Gunfire in Kavaja, shot at a married couple

2025-06-06 11:05:01

Merz: Bashkëpunim i ngushtë Gjermani-SHBA

2025-06-06 10:45:35

A marijuana plantation is found in Cakran, a 24-year-old man is arrested

2025-06-06 10:25:53

Gianni De Biasi shows the formula for how we can win against Serbia

2025-06-06 10:08:57

Hoxha: The CEC was one of the main architects of the destruction of free voting

2025-06-06 09:52:16

Foreign exchange, June 6, 2025

2025-06-06 09:33:01

Accident on the new Kukes bridge, three vehicles collide

2025-06-06 08:43:06

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-06 08:28:14

Clear weather with few clouds, the forecast for this Friday

2025-06-06 08:13:54

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-06 07:46:29

In trial for tender abuse, socialist MP targets ILD

2025-06-05 22:37:09

Tabaku: The left in Albania has shown with facts that it is against integration

2025-06-05 22:09:44

Uzbekistan qualifies for the World Cup for the first time

2025-06-05 21:14:35

Index: Albania among countries that consistently violate workers' rights

2025-06-05 20:53:35

Accident in Burrel, two vehicles collide, 6 injured

2025-06-05 20:31:27

Discover foods that help you relieve stress

2025-06-05 20:16:34

Kalaja: I have a video where votes were taken from the DP and given to the PS

2025-06-05 19:58:04

Berisha: The international community does not accept the farce

2025-06-05 18:57:18

Trump after conversation with Xi: US and China will resume trade talks

2025-06-05 18:35:36

Berisha on May 11: 28 MPs were under the patronage of drug cartels

2025-06-05 18:15:44

The session in the Assembly closes, the majority approves the draft laws alone

2025-06-05 17:55:21

Kurban Bajrami, kreu i Komunitetit Mysliman të Shqipërisë uron besimtarët

2025-06-05 17:29:17

Media at OSCE conference: Organized crime has captured the Albanian state

2025-06-05 16:50:41

Car hits 75-year-old man at white lines in Vlora

2025-06-05 16:42:48

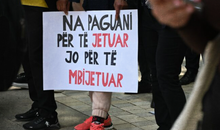

Protest in Spaç, after restoration interventions

2025-06-05 16:27:49

Photo/ Concrete mixer falls into abyss in Ulëz, driver rushed to hospital

2025-06-05 16:15:15

May 11/ Këlliçi: There are attempts to influence the final OSCE-ODIHR report

2025-06-05 16:06:38

Immigration is emptying schools and universities

2025-06-05 15:53:38

Plague breaks out, Kosovo bans import of sheep and goats from Shkodra and Kukësi

2025-06-05 15:48:23

After Tirana, KAS also decides to open the ballot boxes in Dibër

2025-06-05 15:31:03

Tirana is "paralyzed" again, here are the roads that will be blocked tomorrow

2025-06-05 15:20:12