Flash News

Flash News

DASH: Balkans, part of American strategy for expelling migrants

Ilir Shqina, a diplomat, and her business partner Grida Dumas were suddenly born

EULEX mandate in Kosovo extended until 2027

Drug trafficking network dismantled, 11 arrests in Foggia, an Albanian at the center of the investigation

The race for the head of the BKH, the deadline for applications ends today

Quiet villages, wild rivers and unusual adventures, The Time: The secret side of southern Albania

Almost 12 million people visited Albania last year, many of whom headed to the riviera on the promise of an affordable, sun-drenched beach holiday. But the truth is that overtourism is already looming, prices are rising and international investment - including from Jared Kushner, President Trump's son-in-law - means traditional villages are being developed into beach resorts.

If the prospect of sunbathing a few feet away from the Trump family or staying in a hotel that could be anywhere in the world puts you off, there’s a part of the Albanian Riviera that package holiday giants and hotel tycoons tend to miss. Undiscovered Balkans, a small British travel company that specializes in off-the-beaten-path adventures, has introduced a small-group tour to highlight some of the lesser-known treasures of southern Albania.

I joined the trip in May and spent a week exploring lesser-known coastal towns before diving into the country’s interior, where I visited UNESCO World Heritage sites, swam in hidden waterfalls, stayed with farmers high in the mountains, and rafted down one of Europe’s last truly wild rivers. We ended the trip on uncrowded pebble beaches, 200 meters above sea level, in a fishing village on the shores of Lake Ohrid.

I arrived in Qeparo, one of the quietest coastal villages in the Vlora region, in the dark after a three-hour drive from Tirana. I woke up to views of Old Qeparo, the original farming village on the hillside, descending down the mountain to meet New Qeparo on the coast, where beach bars and boat rental centers were preparing for the season.

Our host was the wonderful Mirella Kokëdhima, who runs the guesthouse on her hilltop farm somewhere between the two Qeparos. What she was able to cook after a severe storm and the resulting power outage was impressive and done with a smile. Eggs, goat cheese, yogurt, salad, homemade chocolate cakes, sausages and Turkish coffee so thick you could chew it, all came our way.

At this early season, the sea was too rough for kayaking, so we spent the first day walking along the coast. Our group of eight Brits, aged between thirty and sixty, wandered along karst limestone cliffs with epic views of traditional villages and sparkling water, Corfu a misty hill across the bay. The scent of wildflowers and thyme hung in the air and birds chirped from nearby branches. Nine miles later we landed at Borsh beach and dipped our weary feet in the cool Ionian water, a well-deserved beer in hand.

The next day we turned our backs on the coast and joined our guide, Alfi Pepaj, in a 4×4 for a scenic off-road adventure through the mountains to Gjirokastra, a UNESCO-listed Ottoman-era city. The scenery was dramatic, with peaks carpeted in green and vast, open meadows, with no one around for miles. Along the way, we stopped in the middle of nowhere and followed Pepaj down into a canyon, where a waterfall tumbled.

An hour or so later we arrived in Gjirokastra and were immediately captivated. Our accommodation was a quaint hotel inside an Ottoman house with furniture to match. Nowadays, most will know Gjirokastra for its traditional old town and bazaar, which resembles Bosnia’s Mostar or northern Albania’s Kruja. But the city was also the birthplace of Enver Hoxha, the brutal communist dictator who ruled Albania for 40 years until his death in 1985. It’s a wonder how such an evil man could come from such a beautiful and peaceful country.

The wonderfully preserved 13th-century castle of Gjirokastra offers sweeping views of the region, and its cool stone walls offer a respite from the summer heat. The town is very popular with tourists, but prices were reasonable and an Aperol spritz cost me just £6.

The next morning we set off again into the mountains on another 4×4 tour where more of that spectacular karst landscape awaited us. We traveled along breathtaking trails to the village of Hoshtevë in the neighboring Zagoria region. A few photo stops later, we descended the hill to a 12th-century village church that houses some of Albania’s best-preserved frescoes and icons, having survived several wars, the Ottoman Empire, and Hoxha’s dictatorship.

We returned to Kristina and Ladi Telos’s guesthouse for another Albanian feast. We ate on their wraparound veranda, which was decorated with flowers, citrus trees, and swallows’ nests, not another sound or soul in sight for miles. I couldn’t believe the amount of (fresh) food coming from a kitchen no bigger than most people’s pantry.

E mbushur siç duhet dhe me Pepajn që përkthente, fillova të flisja me Kristinën dhe zbulova se e kishin shndërruar shtëpinë e tyre në një shtëpi mysafirësh 12 vjet më parë, pasi pashë një treg për ushqimin dhe strehimin e shëtitësve që kalonin andej. Një gjë çoi në një tjetër ndërsa Kristina më tregoi përreth dhe gjëja tjetër që dija, po provoja veshjen e saj tradicionale të bareshë dhe po ia modeloja atë pjesës tjetër të grupit.

Qëndrimi ynë i radhës ishte në një shtëpi fshati 120-vjeçare të restauruar me pamje nga lugina e Vjosës, ku rrjedh Vjosa, një nga lumenjtë e fundit vërtet të egër të Evropës. Për të mbërritur atje, kishim ngarë makinën duke u ngjitur në një shteg shkëmbor dheu, or ia vlejti mundi. Tani një ndërtesë e mbrojtur, shtëpia e familjes së Kristaq Cullufes pati fatin të mos u sekuestrohej nga komunistët dhe për një kohë të gjatë mbeti e braktisur. Fshati është një hije e vetes së tij të mëparshme, me shumë njerëz që janë larguar për të gjetur punë diku tjetër.

Pas rënies së komunizmit në vitin 1991, familja e Cullufes u kthye nga qyteti i afërt i Përmetit dhe nisi restaurimin e shtëpisë fshatare. Në dhomën e gjumit në katin e parë ndodhej paja e nënës së tij, një arkë prej druri që nuset shqiptare e mbushnin me gjëra për t'i marrë me vete në shtëpinë e tyre martesore. Në oborr, ku hanim nën tingujt e Vjosës që shpërthente nëpër luginën poshtë, kishte më shumë objekte, duke përfshirë vegla të vjetra bujqësore, makina qepëse dhe telefona.

Më shumë nga ai peizazh malor baritor mbushi dritaret tona të nesërmen, ndërsa udhëtonim drejt Liqenit të Ohrit, ndalesa jonë e fundit. Por jo para se të argëtoheshim në Vjosë, duke bërë rafting në ujëra të bardha, duke zhytur në shkëmbinj dhe duke notuar në natyrë. Mbërritëm përsëri në errësirë, duke i lënë pamjet buzë liqenit një surprizë deri në mëngjes.

I shtrirë përgjatë kufirit me Maqedoninë e Veriut, Ohri i mbrojtur nga UNESCO është një nga liqenet më të vjetra të Evropës. Ne qëndruam në fshatin e qetë të peshkimit të Linit, i cili është një destinacion turistik në hapat e tij të parë dhe lloji i vendit ku njerëzit kanë një varkë në vend të një makine.

Dita jonë e fundit ishte aktive, duke bërë ecje dhe kajak në plazhe të izoluara me guralecë në mëngjes dhe duke përshkuar me biçikletë gjatësinë e pjesës së liqenit që i takon Shqipërisë në pasdite. Nuk ka shezlongje të shtrenjtë këtu. Udhëtimi i këndshëm prej 19 kilometrash na çoi pranë tokave të mbjella, bunkerëve të mbuluar me bimësi, enklavave të qeta ku rosat kërcisnin pas kallamishteve dhe peshkatarëve që shisnin peshkun e tyre buzë rrugës.

Ndaluam në qytetin më të madh të Pogradecit, i cili ka një ndjesi të vërtetë bregdetare britanike: fëmijët qeshën në lojërat e panairit, aroma e karameleve dhe petullave përhapej në ajër dhe të moshuarit thithnin cigare dhe pinin raki ndërsa luanin damë në shëtitore. Pogradeci është një qytet turistik që ka gjetur ekuilibrin e duhur me turizmin - të zhurmshëm, por jo shumë të mbushur me njerëz.

If you prefer to spend your holidays lounging on the beach sipping cocktails, this trip probably isn’t for you. But if you want to experience a more authentic side of Albania, with outdoor adventures and invaluable cultural exchanges, it could be.

Laura Sanders was a guest of Balkans Undiscovered, which offers seven nights all-inclusive from £1,195 per person on an activity-packed holiday in southern Albania. Adapted from The Times

Latest news

Works in Spaç, Lubonja: Destruction of collective and historical memory

2025-06-06 21:54:32

DASH: Balkans, part of American strategy for expelling migrants

2025-06-06 21:12:33

Ilir Shqina, a diplomat, and her business partner Grida Dumas were suddenly born

2025-06-06 20:21:46

Couple injured in Kavaja, police find firearm hidden in wall

2025-06-06 19:05:19

EULEX mandate in Kosovo extended until 2027

2025-06-06 17:58:20

These are the 3 zodiac signs that will be favored in the next decade

2025-06-06 17:50:52

Anthropology

2025-06-06 17:06:00

EU supports International Criminal Court after US sanctions

2025-06-06 16:47:51

Gonxhe ignores concerns about Spaçi and defends the continuation of the works

2025-06-06 16:31:42

Providing online services, report: Institutions, delays in update requests

2025-06-06 16:24:10

The head of the Vlora Cadastre is changed again

2025-06-06 15:58:49

With a rounded belly, Dafina Zeqiri enjoys the holidays with her partner

2025-06-06 15:36:06

Foods that should not be missing from the Eid al-Adha table

2025-06-06 15:04:48

They exploited girls for prostitution in Vlora, 28-year-old arrested

2025-06-06 14:44:26

Israel warns of more attacks in Lebanon

2025-06-06 14:26:30

The race for the head of the BKH, the deadline for applications ends today

2025-06-06 14:15:18

14-year-old girl in Vlora rescued after risking drowning at sea

2025-06-06 14:04:23

Challenge with Albania, Serbian team arrives in Tirana

2025-06-06 13:49:04

He injured the married couple in Rrogozhina, here is who the perpetrator is

2025-06-06 13:34:20

Berisha wishes Eid al-Adha: Blessings to your families and our nation

2025-06-06 13:09:28

He injured his neighbors with a gun, the perpetrator surrendered to the police

2025-06-06 13:02:47

Tom Cruise enters Guinness World Records

2025-06-06 12:38:48

From orange peels to bananas, discover the foods that help you with stress

2025-06-06 12:28:53

How did the feud between Donald Trump and Elon Musk start?

2025-06-06 11:52:32

The prosecution sends 5 Kosovar citizens to trial for drug smuggling

2025-06-06 11:33:56

21-year-old injured with knife in Saranda

2025-06-06 11:24:10

Kosovo citizens flock to the Albanian coast, long queue from Morina

2025-06-06 11:11:07

Gunfire in Kavaja, shot at a married couple

2025-06-06 11:05:01

Merz: Bashkëpunim i ngushtë Gjermani-SHBA

2025-06-06 10:45:35

A marijuana plantation is found in Cakran, a 24-year-old man is arrested

2025-06-06 10:25:53

Gianni De Biasi shows the formula for how we can win against Serbia

2025-06-06 10:08:57

Hoxha: The CEC was one of the main architects of the destruction of free voting

2025-06-06 09:52:16

Foreign exchange, June 6, 2025

2025-06-06 09:33:01

Accident on the new Kukes bridge, three vehicles collide

2025-06-06 08:43:06

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-06 08:28:14

Clear weather with few clouds, the forecast for this Friday

2025-06-06 08:13:54

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-06 07:46:29

In trial for tender abuse, socialist MP targets ILD

2025-06-05 22:37:09

Tabaku: The left in Albania has shown with facts that it is against integration

2025-06-05 22:09:44

Uzbekistan qualifies for the World Cup for the first time

2025-06-05 21:14:35

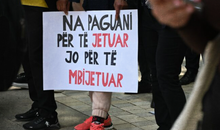

Index: Albania among countries that consistently violate workers' rights

2025-06-05 20:53:35

Accident in Burrel, two vehicles collide, 6 injured

2025-06-05 20:31:27

Discover foods that help you relieve stress

2025-06-05 20:16:34

Kalaja: I have a video where votes were taken from the DP and given to the PS

2025-06-05 19:58:04

Berisha: The international community does not accept the farce

2025-06-05 18:57:18

Trump after conversation with Xi: US and China will resume trade talks

2025-06-05 18:35:36

Berisha on May 11: 28 MPs were under the patronage of drug cartels

2025-06-05 18:15:44

The session in the Assembly closes, the majority approves the draft laws alone

2025-06-05 17:55:21

Kurban Bajrami, kreu i Komunitetit Mysliman të Shqipërisë uron besimtarët

2025-06-05 17:29:17

Media at OSCE conference: Organized crime has captured the Albanian state

2025-06-05 16:50:41

Car hits 75-year-old man at white lines in Vlora

2025-06-05 16:42:48

Protest in Spaç, after restoration interventions

2025-06-05 16:27:49

Photo/ Concrete mixer falls into abyss in Ulëz, driver rushed to hospital

2025-06-05 16:15:15

May 11/ Këlliçi: There are attempts to influence the final OSCE-ODIHR report

2025-06-05 16:06:38

Immigration is emptying schools and universities

2025-06-05 15:53:38

Plague breaks out, Kosovo bans import of sheep and goats from Shkodra and Kukësi

2025-06-05 15:48:23

After Tirana, KAS also decides to open the ballot boxes in Dibër

2025-06-05 15:31:03

Tirana is "paralyzed" again, here are the roads that will be blocked tomorrow

2025-06-05 15:20:12

Serbia is coming to Albania tomorrow, here's where it will be accommodated

2025-06-05 14:24:43

US Embassy updates visa appointment system: More flexibility for applicants

2025-06-05 14:21:01

Drug trafficking with "tentacles" in Europe, GJKKO seals prison for 9 arrested

2025-06-05 13:39:35

Deserting from the socialist ranks, Erion Braçe "becomes" a Democrat

2025-06-05 13:23:49

May 11 elections, KAS decides on a full recount of votes in Tirana

2025-06-05 13:22:28

Clashes in the Parliament/ Elisa Spiropali expels Flamur Noka from the session

2025-06-05 13:04:42

A Girl, Otherwise, A Boy

2025-06-05 12:57:30

Accident at the "Albchrome" factory in Elbasan, three people arrested

2025-06-05 12:54:40

Berisha: The law of farce is that the dictator's votes are always increasing

2025-06-05 12:19:16