Flash News

Flash News

Arrests of "Bankers Petrolium", Prosecution provides details: Exported and sold 532 billion lek of oil, caused millions of euros in damage to the state

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

Ceno Klosi with over 800 stolen votes, Balluku finds the reason is the tiredness of the counters

"Fast & Furious" in the former Block, police chase an Audi Q8, 4 cars collide

Why does Blendi Kajsiu analyze 'Berishism' in a test tube, not in real life?

Alfred Lela

Blendi Kajsiu has been visibly concerned with developments in the opposition following the May 11th elections. More precisely, with what he paraphrases al grosso modo as “Berishism.”

In methodology—that is, the tools and research methods chosen to conclude—Kajsiu appears to have the rational end predetermined, using the methodology not as an instrument to reinforce the thesis, but as a lever to move a subconsciously shaped narrative.

In his writings—numerous on this topic—Kajsiu seems to be pursuing a doctorate in “Berishism,” but even here with a methodological deviation: he bypasses context. He treats Berisha and “Berishism” as detached from their circumstances, as something that exists on its own, in a test tube—not in real life—regardless of social and political conditions.

He performs a quantitative, not qualitative, analysis. For this reason, he focuses on “how much Berisha lost,” “how much PD declined,” “how many left and how many joined,” avoiding the very aspect that could most accurately explain what is happening in Albania with elections. That can only be done through a qualitative analysis.

Only this kind of analysis allows one to answer the fundamental question: how is it possible that a Prime Minister like Rama, 12 years in power, wins a fourth mandate despite a governance that, even in the eyes of the most PS-friendly observers, can at best be described as problematic?

If we pose this essential question and use methodology in service of it, then “Berishism” falls apart. The failure to raise this thesis, in Kajsiu’s case and others’, reveals precisely that the authors in question seek to invent an opposition beyond Berisha—because they do not (or do not want to) unpack a power like Rama’s.

Besides avoiding such an analysis, Kajsiu and others fall into a paradox, because they attempt to explain the political superstructure not through the structures of power, but through its challengers.

Another thing they avoid, hidden behind this approach, is explaining society’s powerlessness (including that of the doctoral candidates of this thesis themselves) to produce antibodies against a regime that swells as it ages, and is sanctified even as it grows corrupt.

On this level, I challenge Kajsiu—also because he is perhaps the only among the anti-Doctor doctoral candidates who could pose and develop arguments on this terrain. This is because I don’t think he holds a sponsored thesis of “Berishism”—rather it’s a perspective from which he tries to explain the politics of power/opposition in Albania. Besides, he has the academic training and reading depth to interpret an Albania that—yes—is partly described by “Berishism,” but is not defined by it by default.

That said, it must also be emphasized that treating both Albania’s political scene and Sali Berisha himself the same in the early 1990s as in the mid-2020s is a gross distortion of the goal to offer a comprehensive analysis.

The non-political-science-like focus on “Berishism” and the opposition as an explanation for the impossibility of rotation betrays a desire to leave “rotation” as merely a terminological construct—viewing any change of power that does not happen beyond “Berishism” as a risk.

If Kajsiu and others adopt Rama’s terminology—“there can be no change in power without a change in the opposition”—then power never changes. Because societal expectations are canceled through simulation, and the premise shifts from “change of power” to “change of opposition.” Given that the opposition, by definition, has far fewer tools and methods of narrative/propaganda/influence/pressure, there will always be incentives and mechanisms in the courtyard of power to “politologically prove” that the opposition hasn’t changed—even when it has (say, even if—as many left-wing analysts seem to desire—another doctor, Ilir Alimehmeti, comes to lead the right).

This paradox, where a self-declared leftist like Kajsiu speaks of the dangers posed by the minority as greater than those of the majority—and demands that the minority be purified, while power continues to marinate in the same vices—is an ad absurdum in itself.

On the other hand, Kajsiu avoids the “other” opposition from intellectual debate—a topic that Bushati, with whom he has sparred indirectly three times recently, has touched upon: the groupings of Shehaj, Lapaj, and Qori. If Berisha is Kajsiu’s hostage—and the hostage-taker of the broader opposition block (PD)—then why didn’t voters (unpressured, according to Kajsiu) migrate to the Independent or New Opposition block?

For a simple reason: when the machinery of power distorts elections, it does not differentiate among “oppositions.” As a mechanism of the superstructure, it cannot be eclectic (selective). It is egalitarian in the worst sense—it suppresses all equally: Berisha and Shehaj alike. It makes no distinction between them, because it considers only itself as the distinction—note Rama’s rhetoric: “we’re not the best, but there’s no one better than us.”

Here is another dimension where Kajsiu could untangle his reasoning: why, even when there were alternatives beyond “Ramaism” and “Berishism,” were they ignored by the electorate? So much so that even a party like PSD of Tom Doshi, which could be viewed as a byproduct of the system, if we use Kajsiu’s reasoning—won more MPs than “The Young Ones.”

For this reason, I think Kajsiu needs to return to qualitative analysis. That is, how Rama has qualitatively transformed (by which I mean the essence, not the quality in a normative sense) the political and electoral landscape in Albania.

Numbers unsupported by facts do not explain reality—they engineer it. And that is the nature of the question: why does power grow when the nature of power itself is regressive?

In this case, let us remember the essential point: we are speaking of a democracy, not an autocracy!

Latest news

A unique summer season, full of rhythm and rewards for Credins bank customers!

2025-07-03 12:12:20

Fire situation in the country, 29 fires reported in 24 hours

2025-07-03 12:00:04

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 41st time

2025-07-03 11:59:57

The gendering of politics

2025-07-03 11:48:36

The price we pay after the "elections"

2025-07-03 11:25:39

Xhafa: The fire at the Elbasan landfill was deliberately lit to destroy evidence

2025-07-03 11:08:43

The 3 zodiac signs that will have financial growth during July

2025-07-03 10:48:01

Democratic MP talks about the incinerator, Spiropali turns off her microphone

2025-07-03 10:39:24

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

2025-07-03 10:21:03

Cocaine trafficking network in Greece, including Albanians, uncovered

2025-07-03 10:10:12

Korreshi: Election manipulation began long before the voting date

2025-07-03 09:39:13

Arrest of Greek customs officer 'paralyzes' vehicle traffic at Qafë Botë

2025-07-03 09:28:41

After Tirana and Fier, the boxes are opened in Durrës today

2025-07-03 09:21:10

Enea Mihaj transfers to the USA, will play as an opponent of Messi and Uzun

2025-07-03 09:10:04

Foreign exchange, the rate at which foreign currencies are sold and bought

2025-07-03 08:53:50

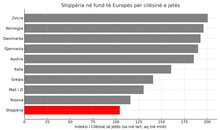

Index, Albania has the worst quality of life in Europe

2025-07-03 08:48:10

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-07-03 08:17:05

Clear weather and high temperatures, here's the forecast for this Thursday

2025-07-03 08:00:37

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

2025-07-03 07:46:48

Lufta në Gaza/ Pse Netanyahu do vetëm një armëpushim 60-ditor, jo të përhershëm?

2025-07-02 21:56:08

US suspends some military aid to Ukraine

2025-07-02 21:40:55

Methadone shortage, users return to heroin: We steal to buy it

2025-07-02 20:57:35

Government enters oil market, Rama: New price for consumers

2025-07-02 20:43:30

WHO calls for 50% price hike for tobacco, alcohol and sugary drinks

2025-07-02 20:41:53

Israel agrees to 60-day ceasefire in Gaza, but many unanswered questions remain

2025-07-02 18:35:27

The weather in Germany is going "crazy", temperatures reach 40°C

2025-07-02 18:22:21

"Fast & Furious" in the former Block, police chase an Audi Q8, 4 cars collide

2025-07-02 17:59:25

"Birth on a tourist visa? US Embassy warns Albanians: This is prohibited!"

2025-07-02 17:48:16

BIRN: Fier recount reveals vote trafficking within open political party lists

2025-07-02 16:57:19

CEO and former director of 'Bankers Petroleum' arrested in Fier

2025-07-02 16:40:42

Car hits two tourists on a motorcycle in Fushe Arrëz, one of them dies

2025-07-02 16:33:23

Fire at the Elbasan Incinerator Landfill, Prosecution Launches Investigations

2025-07-02 15:34:54

What you need to know if you travel to a country with active volcanoes

2025-07-02 15:33:03

EU proposes 90% reduction in greenhouse gases by 2040

2025-07-02 14:50:23

Europe is burning from the heat / Italy and France are on maximum alert

2025-07-02 14:36:52

Moscow's contradictory statements: Is the friendship with Vučić breaking down?

2025-07-02 14:21:05

'I lost my battle': Sea warming is killing fishing in Albania

2025-07-02 14:08:35

Sekretet kimike që ndihmojnë në mbajtjen e mjaltit të freskët për kaq gjatë

2025-07-02 14:01:26

Denmark makes historic decision to make military service mandatory for women

2025-07-02 13:44:33

The appeal of the GJKKO leaves former judge Pajtime Fetahu in prison

2025-07-02 13:30:20

Productivity losses could reduce GDP by 1.3% as a result of extreme heat

2025-07-02 13:21:04

He abused his minor daughter, Zamir Meta is left in prison

2025-07-02 13:04:04

Waste burning in Elbasan, Alizoti: They are poisoning people and stealing money

2025-07-02 12:48:39

Civil disobedience continues in Serbia, dozens of people detained

2025-07-02 12:40:32

Rama's government was born under the sign of garbage and will end like this

2025-07-02 12:28:09

Water prices increase in the municipalities of the Elbasan region

2025-07-02 12:13:38

Civil disobedience continues in Serbia, what is happening in Belgrade?

2025-07-02 12:07:44

Serious accident in Thumanë, one dead, 3 injured

2025-07-02 11:54:42

Durrës Court suspends the director of Pre-University Education from duty

2025-07-02 11:49:27

Plenary session on Thursday, what is expected to be discussed

2025-07-02 11:36:43

Europe is burning from heat waves/ What is the 'thermal dome' phenomenon?

2025-07-02 11:26:25

Wanted by Italy for murder, 45-year-old arrested in Vlora

2025-07-02 11:19:31

Fire situation, 28 fires reported in 24 hours, 2 still active

2025-07-02 11:13:20

"Buka" file, preliminary hearing for Ahmetaj postponed to July 17

2025-07-02 11:03:30

Baçi: Belinda Balluku and Ceno Klosi, the most dangerous "gangs" in Fier

2025-07-02 10:32:09

Zamir Meta, suspected of sexually abusing his daughter, arrives in court

2025-07-02 10:21:33

Trump: Israel has agreed to a 60-day ceasefire in Gaza

2025-07-02 10:01:55