Flash News

Flash News

Tragic accident on the "Ibrahim Rugova" Highway, a woman from Fushë-Kruja loses her life

Justice pardons Xhaçka, Special Appeal decides not to investigate former minister

Berisha evaluates OSCE report: They have ruined the elections

The Supreme Court returns Arbër Veliaj's appeal for retrial

Call Center raided in Tirana/One of the organizers and 6 employees in handcuffs

Free and fair? Albania's elections reflect a worrying global trend

In a world where interest-driven foreign policies take precedence over democratic standards, the abuses documented during Albania's parliamentary elections are unlikely to face much criticism - allowing the ruling Socialist Party to consolidate power.

Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama's Socialist Party has secured a landslide election victory once again, with promises to lead Albania towards membership in the European Union within the next four years.

But the outcome of last Sunday’s election seemed sealed long before the ballots were cast. The Socialists relied on a well-oiled patronage machine. With some 185,000 civil servants in Albania’s public sector, the implicit message was unmistakable: support the party or risk your job.

In an attempt to regain political influence, the center-right opposition Democratic Party, led by Sali Berisha, attempted to imitate the aggressive political strategy of US President Donald Trump's MAGA movement.

The party even brought in Chris LeCivita, a key architect of MAGA’s communications tactics. The decision was more than symbolic. Berisha seemed to be betting that embracing Trump-style politics could pave the way for a political comeback and potentially convince Washington to lift sanctions against him and his family.

However, this strategic gamble appears to have misjudged both the entrenched power of Prime Minister Rama and the Socialist Party, as well as the broader geopolitical landscape. The United States has long pursued a pragmatic, interest-oriented foreign policy, prioritizing engagement with a strong, centralized leadership over ideological compliance – and Rama has kept his promises. Against this backdrop, Berisha’s gamble appears to have backfired, leaving both the message and the messenger to fail.

On the other hand, smaller independent parties faced a herculean task of organizing a meaningful campaign. In an environment increasingly hostile to dissent, their supporters were often reluctant to show public allegiance, fearing professional or social repercussions – especially in smaller towns and rural areas where political affiliations are more visible and the control of the ruling party is stronger.

Qasja në media përbënte një tjetër pengesë e madhe; me pjesën më të madhe të rrjeteve televizive dhe mediave të shtypura, qoftë shtetërore, ose të kontrolluara fort nga interesat e biznesit pro-qeveritar, partitë e pavarura luftonin për të marrë kohë transmetimi ose mbulim nga shtypi. Kur ata ia dolën të arrinin te publiku, mesazhet e tyre shpesh mbyteshin nga saturimi mediatik dhe makineria e rafinuar e propagandës së partisë në pushtet.

Kandidatët e tyre u përballën gjithashtu me pengesa burokratike, nga rregullat kufizuese mbi regjistrimin dhe aksesin në fletëvotime deri te procedurat e errëta që favorizonin në mënyrë disproporcionale partitë më të mëdha dhe të konsoliduara. Në raste të shumta, monitoruesit e zgjedhjeve vunë re raste ku përfaqësuesit e partive të pavarura u ngacmuan ose u kanosën, duke dekurajuar më tej pjesëmarrjen qytetare dhe duke përforcuar perceptimin se sfidimi i status quo-së ishte i kotë.

Si rezultat, këto forca më të vogla politike, të cilat mund të kishin futur ide të reja në arenën politike të ndenjur të Shqipërisë, u lanë kryesisht mënjanë – u bënë të padukshme nga një sistem i projektuar për të forcuar dominimin e elitës sunduese.

Regresi demokratik

Zgjedhjet nxorën në pah shqetësimet në rritje mbi regresin demokratik nën qeverinë e Ramës. Sipas Misionit Ndërkombëtar të Vëzhgimit të Zgjedhjeve të OSBE-së, keqpërdorimi i burimeve publike dhe presioni administrativ gjatë procesit zgjedhor ishin të përhapura.

Qeveria e Ramës është akuzuar gjerësisht për korrupsion, për shtypje të lirive të medias dhe për zgjerimin e administratës publike me 25,000 vende të reja pune – të parë si përforcues i sistemit të patronazhit – ndërsa vendi vazhdon të përballet me një krizë masive emigrimi. Që nga rënia e komunizmit në vitin 1990, popullsia e Shqipërisë është ulur me 15 për qind në 2.4 milionë, pjesërisht për shkak të emigrimit.

Raporti i vëzhguesve vuri në dukje shtrëngimin sistematik të punonjësve të sektorit publik, mbulimin e anshëm të medias së kontrolluar nga shteti dhe një mungesë të vazhdueshme të vullnetit politik për të miratuar reformat zgjedhore të vonuara prej kohësh. Vetë fushata u përshkrua si thellësisht e polarizuar dhe e dëmtuar nga përpjekjet për të manipuluar votuesit përmes kanosjes dhe blerjes së votave. Vëzhguesit raportuan gjithashtu raste të shpeshta të votimit në grup dhe familjar, shkelje të rënda procedurale dhe ndërhyrje nga eksponentë të partisë.

Pavarësia e medias u komprometua rëndë nga financimi jotransparent, pronësia e përqendruar dhe ndërhyrja politike në vendimet editoriale. Në përgjithësi, përdorimi i burimeve shtetërore nga partia në pushtet dhe taktikat shtrënguese i dhanë asaj një avantazh të padrejtë, duke hedhur dyshime mbi integritetin dhe drejtësinë e zgjedhjeve.

In today's increasingly illiberal environment, many of these undemocratic strategies have become more the norm than the exception, reflecting a broader regional and global trend in which democratic institutions are hollowed out from within.

What once would have provoked international condemnation is now viewed with muted concern, as strategic alliances, migration containment, the construction of immigration detention centers, and regional stability often take precedence over democratic values. In this context, Albania’s decline is not an exception, but part of a broader erosion of liberal democratic norms – where procedural elections persist, but the spirit of democracy steadily fades.

Consolidation of power

Rama and his government have effectively built a one-party system of government, consolidating power through a mix of institutional control, systemic patronage, and the suppression of dissent. The opposition has not been neutralized by force, but by a calculated erosion of democratic competition, leaving Albania with the image of electoral democracy but with few of its essential guarantees.

Meanwhile, endemic poverty persists, corruption remains deeply entrenched in both the public and private sectors, and an accelerating exodus of citizens – particularly young and educated Albanians – reflects a widespread disillusionment with the country’s trajectory.

Yet, despite this bleak domestic landscape, Rama continues to cloak his rule with the rhetoric of European integration, hoping that the promise of eventual EU accession will mask the erosion of democratic standards in the country.

The irony is grim: as Albanians continue to leave the country in search of the freedoms and opportunities that the EU represents, their government consolidates a regime increasingly distant from the union's fundamental values.

Yet, in the delicate balance of regional geopolitics, European leaders have shown little appetite to challenge Rama’s slide toward illiberalism. The hope, however faint, is that one day Albania will not only join the EU in name, but will embody the democratic spirit it once aspired to. /BIRN/

Latest news

Parties and candidates did not respect media freedom and transparency

2025-05-14 18:42:28

Video/ Heavy traffic at the exit of Tirana, chaos on the Tirana-Durrës highway

2025-05-14 18:09:52

Lapaj reacts after securing 1 mandate: I will make you curse yourself

2025-05-14 17:13:30

'We have the government we deserve': Students are distrustful of elections

2025-05-14 16:49:42

Elections in Albania, DW: Maintaining power through dubious means?

2025-05-14 15:43:10

The US should not recognize the rigged elections in Albania

2025-05-14 15:18:14

Tension in CEAZ no. 31 in Tirana, vote counting suspended after clashes

2025-05-14 15:13:32

Berisha evaluates OSCE report: They have ruined the elections

2025-05-14 14:45:11

SPAK and BKH action in Shkodra, some escorted for electoral crimes

2025-05-14 14:05:26

This type of food can increase the risk of a deadly disease

2025-05-14 13:54:51

EU adopts new sanctions package against Russia

2025-05-14 13:30:51

Albanians' spending on private education reached 200 million euros in a decade

2025-05-14 13:20:22

The poorest president in the world passes away

2025-05-14 13:10:33

Australia, death toll from melioidosis outbreak in Queensland rises to over 30

2025-05-14 13:01:07

The Supreme Court returns Arbër Veliaj's appeal for retrial

2025-05-14 12:52:25

Call Center raided in Tirana/One of the organizers and 6 employees in handcuffs

2025-05-14 12:40:42

Kidnapping and threats in Astir, 29-year-old arrested

2025-05-14 12:34:57

Free and fair? Albania's elections reflect a worrying global trend

2025-05-14 12:28:34

Facebook's Zegjineja also a Member of Parliament

2025-05-14 12:16:40

Diaspora vote, Nuri: Work done by patronage, strong shadows of suspicion

2025-05-14 12:07:33

Fight with crowbars and gunfire in Tirana, police official reaction

2025-05-14 11:41:10

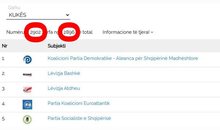

Fraud or manipulation?! Diaspora envelopes in Kukës are increasing by counting

2025-05-14 11:29:48

"We protect the vote", Berisha reveals the slogan of the May 16 protest

2025-05-14 11:11:02

Electoral crime/ SPAK publishes figures: 7 people arrested

2025-05-14 11:03:08

Accident at Tujani Stairs, two young people lose their lives

2025-05-14 10:51:01

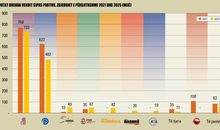

"SP gets 84 mandates", how did Open Data predict the results of May 11?

2025-05-14 10:28:28

Tirana Court Sentences Dan Hutra, Serial Killer of Women, to Life in Prison

2025-05-14 10:10:55

List of MPs that Elbasan is bringing to the Assembly

2025-05-14 10:01:46

"Zjerm" leads Albania to the Eurovision 2025 final

2025-05-14 09:50:29

New parties open a window to Parliament for the first time

2025-05-14 09:31:45

Rama delivers a speech at Skanderbeg Square today

2025-05-14 09:31:34

Shkëlqim Shehu wins mandate, most voted in Kukës from DP

2025-05-14 09:11:58

Votes for candidates, names from the open list entering the Assembly in Lezha

2025-05-14 09:03:23

How was the vote stolen in London? Hasjani tells it live

2025-05-14 08:37:52

About 80 thousand envelopes from the diaspora are being counted, results so far

2025-05-14 08:30:37

Foreign exchange/ How much foreign currencies are bought and sold today

2025-05-14 08:13:53

4 cars collide in Tirana, after the accident the drivers fight with levers

2025-05-14 07:58:20

Weather forecast for today

2025-05-14 07:40:35

HOROSCOPE/ Here's what the stars have predicted for each sign

2025-05-14 07:20:57

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-05-14 07:06:32

SP towards full legislative control, what does this mean for democracy?

2025-05-13 22:36:52

'Braçeee, Braçeee', the counter grabs the attention of CEAZ 5, laughter erupts

2025-05-13 21:55:09

Tirana hosts European leaders on May 16, summit agenda revealed

2025-05-13 21:11:22

Counting closes in Vlora, PS gets 9 mandates, DP remains with 3

2025-05-13 20:59:14

DP representative at the CEC: SP votes in the diaspora, filled by the same hand

2025-05-13 20:50:55

BIRN: European Union concerned about violation of electoral standards in Albania

2025-05-13 20:21:37

A house for a vote? Soft loans for the administration before the elections

2025-05-13 20:10:01

DP-ASHM secures two mandates in Kukës, Isuf Çelaj the most preferred voter

2025-05-13 20:01:22

Poll/ Were the May 11 elections fair?

2025-05-13 19:27:22

Elections 2025/ Counting of diaspora votes continues, results

2025-05-13 19:21:11

Lapaj: We are close to a mandate in Fier, we will take it from the SP

2025-05-13 19:17:33

82 mandates, a reward for what?

2025-05-13 18:36:46

International cyber fraud network hit, seizures and checks in Tirana

2025-05-13 18:17:08

"Electronic Shkodra" takes to the Eurovision 2025 stage tonight

2025-05-13 16:02:42

Discover the 5 reasons to take folic acid even if you are not pregnant.

2025-05-13 15:45:50

Lack of independent media undermined elections, observers say

2025-05-13 15:34:36

The first ballot boxes for candidates in Rrogozhina are being counted.

2025-05-13 15:31:42