Trump is upending the world order that America built

Ndërsa presidenti afrohet Putinin, aleatët e vjetër kanë filluar ta shohin SHBA-të si jo të besueshme, dhe si një kërcënim të mundshëm për sigurinë e tyre.

Jaroslav Trofimov / Wall Street Journal

America's 80-year run as the world's strongest power, a relatively benevolent hegemon that attracted willing partners and allies, has been rooted in two major US initiatives launched in response to the upheaval of World War II.

One was to convene the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, which enshrined the idea of free trade and low tariffs, generating unprecedented prosperity for the West. The other, five years later, was to lead the establishment of NATO, an alliance that won the Cold War and has ensured peace in Europe.

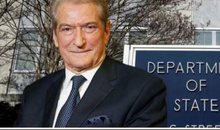

To fashion this system out of the chaos and rubble of world war, wrote Dean Acheson, a key adviser to Roosevelt and Truman throughout this period, required America to make "an imaginative effort unique in history and even greater than that made in the preceding period of fighting." Acheson, who first entered politics in the 1930s to combat "America First" isolationists, called his memoir "Present at the Creation."

President Harry Truman, left, and his Secretary of State Dean Acheson, seen here in 1949, cemented America's global leadership after World War II. Photo: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Both of these legacies are being undone with stunning speed by President Trump. His second administration has targeted America's closest allies with punitive tariffs, has ordered an abrupt stop to military assistance for Ukraine, has frozen foreign aid—and is raising the prospect of a geopolitical realignment toward authoritarian Russia.In Tuesday's address before Congress, Trump said that "we've been ripped off for decades by nearly every country on earth, and we will not let that happen any longer," adding that now "we reclaim our sovereignty."

His moves have sent the rest of the world scrambling for a response, a profound reshaping of the international order in which America's erstwhile allies are starting to view the US as not just no longer reliable, but perhaps as an outright threat to their own security.

"The US has switched sides from standing with democracies like Canada, like France, like Japan, and is now standing with dictators like Putin. People in free countries all around the world should be very concerned," said Canadian lawmaker Yvan Baker, echoing a view that is also rapidly becoming a European consensus.Trump has already slapped Canada, with whom he had negotiated a free-trade agreement in his first administration, with 25% tariffs, although he soon paused most of them for the moment. He says he wants the country to stop being an independent nation and join the US as the 51st state. "Trump questioning our sovereignty and trying to destroy our economy is right out of Putin's playbook," Baker said.

France's President Emmanuel Macron, in a dramatic address to the nation on Wednesday that asked for a major rearmament drive, said that Europe cannot allow its future to be decided by Washington and Moscow, and that it must now prepare for an America that is no longer by its side.

"We are entering a new era," Macron said. "Our generation will no longer benefit from the dividends of peace, and it depends on us whether our children tomorrow will be able to collect the dividends of our commitments."

There was a similar despondency among allies during Trump's first administration, but by the end of his term the NATO alliance had emerged stronger and Russia weaker, said Matthew Kroenig, senior director of the Scowcroft Center at the Atlantic Council in Washington who served at the time as a senior Pentagon adviser.

"People are overreacting to rhetoric and symbolism, and not paying enough attention to underlying results," he said. "If six to 18 months from now, our NATO allies are spending more and there is a ceasefire in Ukraine, I would argue that we'd be in a better place than today."

As the Trump administration moved this week to cut off military aid and vital intelligence to Ukraine, the president threatened on Friday to impose more sanctions and tariffs on Russia if it does not come to the negotiating table. Russia's current trade with the US is marginal.

In his first presidency, Trump openly questioned the value of alliances and free trade, while expressing admiration for authoritarian leaders and contempt for fellow democracies, particularly in Europe. But today, with virtually no opposition in Congress or within the administration, those impulses are pursued with unrestrained, and unmatched, vigor. There is also a new, much more destabilizing ingredient: predatory claims on foreign land, such as Canada, Greenland, the Panama Canal and even the Gaza Strip.

"In his first term, Trump believed that America was played for a sucker. His response was retrenchment," said Michael Fullilove, executive director of the Lowy Institute think tank in Australia. "In his second term, the same conviction is pushing him outwards. Now Trump wants more protection money and more territory—and he is prepared to use coercion to get those things."

Trump administration officials frequently refer to their policy in the Western Hemisphere as "Monroe Doctrine 2.0"—a new incarnation of the 19th-century claim to dominate the Americas.

While Trump says he seeks global peace with his radical shifts in America's generations-old consensus, the explosive combination of his neo-mercantilism and his embrace of 19th-century-like imperial thinking could actually push the world toward a new conflagration, warned Evelyn Farkas, executive director of the McCain Institute, who served as US deputy assistant secretary of defense for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia under President Obama.

"Both aspects of his foreign policy, the security component as well as the trade and economic component, hold a lot of danger, not just for the United States but for the world," she said. "We are seeing actions put into place that contain the kernels of a potential world war."

Chairs are removed from the signing table at the White House after the disastrous meeting between President Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, Feb. 28. Photo: Carol Guzy/Zuma Press

Trump's drastic shift is not rooted in American public opinion. A recent CBS-Yougov poll showed that 52% of Americans support Ukraine, versus just 4% supporting Russia. Most Americans, including 59% of Republicans, consider Russia to be either an unfriendly power or an outright enemy, according to the survey. Another poll, by Reuters-Ipsos this month, found that 50% of Americans disapprove of Trump's foreign-policy moves, and only 37% approve, a 15% decline in net approval since January."The president has a mandate to try to stop the war, but not to pull the rug out from under Ukraine, switch sides, turn over Ukraine to Russia and adopt a spheres-of-influence posture in the world," Farkas said.

The US has not always been a benign world power over the past eight decades, of course. It supported coups and repressive dictatorships in Latin America, Africa and Asia and invaded and occupied Iraq in 2003. But, for more than a century, it did not attempt to permanently seize other nations' territory. And, in a global contest with authoritarian rivals, it stood as the champion of human rights and democratic values that have taken root around the world under American tutelage, particularly in the nations that it defeated in 1945.

Trump's trade wars, his humiliation of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, threats to Canada, Panama and Denmark, and the sidelining of European allies have eroded that legacy around the world, including in Asia. America's image in Asia has changed "from liberator to great disrupter to a landlord seeking rent," said defense minister Ng Eng Hen of Singapore, one of Washington's closest Asian partners.The critical question these Asian allies are asking themselves is whether, after seeming to accept Russia's right to a sphere of influence in Europe, the Trump administration would also seek a similar accommodation over their heads to divvy up the world with China's Xi Jinping.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, front, and Russian President Vladimir Putin at the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia, Oct. 24, 2024. Photo: Ramil Sitdikov/brics/Associated Press

Trump's choice for undersecretary of defense for policy, Elbridge Colby, raised eyebrows by testifying during his recent confirmation hearings in the Senate that Taiwan, while being very important to the United States, is not an "existential interest." Trump has threatened to impose tariffs on Taiwan, too, as part of his economic moves against America's closest trading partners."China has always thought that America's greatest asymmetric advantage was its alliance system, and now that the US is alienating its allies, China is delighted to see the tensions between the US, Europe and Canada," said Rush Doshi, a scholar at the Council on Foreign Relations and Georgetown University who served as deputy senior director for China and Taiwan in Biden's National Security Council. "And obviously, a US that retreats into the Western Hemisphere is going to be outplayed by a China that goes truly global."

Amid this sea change in the world, China is already trying—not without success—to portray itself as a force for global stability, free trade and prosperity. China's special envoy for European affairs, Lu Shaye, said Wednesday it was appalling how Trump has treated Europe, and agreed with the European leaders that the future of Ukraine should not be decided just by Washington and Moscow.

"European friends should reflect on this and compare the Trump administration's policies with those of the Chinese government," Lu said. "In doing so, they will see that China's diplomatic approach emphasizes peace, friendship, goodwill and win-win cooperation."

European governments—well aware that Russia has been able to endure three years of war largely thanks to Chinese economic and political support—aren't likely to take these overtures at face value. But in a new world where the US is going from strategic ally to predator, some rebalancing appears inevitable.

European nations collectively are America's largest trading partner, and the largest source of foreign investment into the US Until now, they have clung to hopes that the trans-Atlantic bond that endured eight decades would somehow survive.

Ukrainians visit the graves of soldiers at a military cemetery in Lviv on Feb. 23, 2025, on the eve of the third anniversary of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Photo: yuriy dyachyshyn/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

European leaders welcomed Ukrainian President Zelensky at a summit in London on March 2, days after his meeting with President Trump. Left to right: French President Emmanuel Macron, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer, Zelensky and Poland's Prime Minister Donald Tusk. Photo: christophe ena/Press pool

Trump's open embrace of Russian positions over Ukraine in recent weeks has shattered that illusion. "We used to have wake-up calls, but in recent days we received an electroshock," said Wolfgang Ischinger, a former German ambassador to Washington and a former chairman of the Munich Security Conference. In a recent opinion poll by French broadcaster BFMTV, 73% of French respondents said they no longer considered the US an ally—and 67% supported sending French troops to Ukraine to police a cease-fire.Nowhere is the mood shift more abrupt than in eastern and central Europe, which has been for decades among the most pro-American parts of the world. While French strategic thinking, underpinned by a fully independent nuclear weapons force, is shaped by what Paris and London viewed as an American betrayal during the 1956 Suez crisis, countries such as Poland or the Czech Republic have long credited Ronald Reagan's America for their freedom.

Former Polish President and Nobel Peace Prize winner Lech Walesa, the founder of the Solidarity movement that challenged Communist control of Poland in 1980, puts Trump and Vice President JD Vance in a very different category. The scene of Zelensky's humiliation in the Oval Office reminded him "of interrogations at the hands of the Security Service and the courtrooms of Communist tribunals," Walesa wrote in a letter signed by 39 fellow former dissidents, adding that Communist judges and prosecutors at the time "also used to tell us that they hold all the cards, while we have none."How do you think President Trump's foreign policy will reshape the world? Join the conversation below.

Existential choices are looming in the immediate future for the 500 million Europeans, most of whom are not yet prepared for the costs—such as higher taxes and less social welfare—that would be required to rearm for the harsh new reality, said Rym Momtaz, a Paris-based analyst at the Carnegie Endowment."This presents the Europeans with a new, vital, multigenerational choice: What do they do? Are they capable of becoming the fourth pole, so that they are not subsumed into the spheres of influence of Russia, the US or in some way China?" she wondered. "Or will they accept that they can't, and then there will be a division of Europe."

The 27-member European Union—which includes Hungary, a country hostile to Ukraine and aligned with Trump—won't be able to develop anytime soon into a meaningful security actor in its current shape, said Ischinger. The way forward, he suggested, is for some kind of new European Defense Union, with one European defense-industrial market, that would include a coalition of willing EU members plus the UK and Norway.

Retired Air Marshal Edward Stringer, a former head of operations at the British defense staff, said that some sort of "east Atlantic alliance"—possibly also including Canada—could replace NATO in the coming years. "Europe has a fleeting opportunity to step up to the challenge posed directly and indirectly by Putin and Trump," he said. "Can it mobilize its latent power and take control of its security architecture—or will it become a vassal?

Europe's biggest economy, Germany, is certainly taking dramatic steps. Incoming Chancellor Friedrich Merz is pushing next week a sea change in the country's security policy, with constitutional amendments that would adjust limits on public debt and allow Berlin to spend hundreds of billions of euros on military procurement. Some two-thirds of European military spending went until now to American defense companies, a crucial connective tissue in the alliance.

But Trump's sudden cutoff of military aid to Ukraine—a country that, European leaders say, is engaged in a war that is existential to Europe's own security—is likely to prompt European nations to prioritize in the future weapons systems that could not be restricted or disabled by Washington.

"We've always followed the principle of hoping for the best, but now we are finally getting around to preparing for the worst—the US becoming an openly hostile power aligned with Russia," said Thorsten Benner, director of the Global Public Policy Institute in Berlin. "Is it too late? We'll see, but it is certainly late in the game."

While the fraying of alliances between the US and fellow democracies certainly favors China, the biggest winner at the end could be Europe, said retired US Navy Adm. James Stavridis, who served as NATO's supreme allied commander. "Events in which the United States disengages could cause Europe to come together with will and unity, and make it a far more important force in international relations," he said.

In his memoir, Dean Acheson noted the rapid collapse of world powers and the sudden disappearance of ancient empires. One of the great architects of the post-World War II order, he lamented the dangerous belief that in international affairs, "as in women's fashions and automobile design, novelty and change are essential to validity and value."

Acheson argued for the opposite: "The simple truth is that perseverance in good policies is the only avenue to success."

Latest news

How did LaCivita change the DP campaign? Berisha: He studied the opponent

2025-05-08 22:49:51

David defeats Goliath

2025-05-08 22:15:50

Journalist: There are SPAK infiltrators in party headquarters

2025-05-08 21:55:15

Who is the new Pope?

2025-05-08 21:48:13

Berisha finally reveals when he will retire from politics

2025-05-08 21:33:46

LaCivita in Lezha: Albanians will fire Edi Rama from his job

2025-05-08 21:11:20

Berisha: LaCivita chose us because he believes in Reagan's program

2025-05-08 20:48:40

He rejected America to serve Pogradec, Genti Çela tells about life in "Elevate"

2025-05-08 20:26:28

Pope Leo XIV greets the faithful for the first time in St. Peter's Square

2025-05-08 19:29:33

Photo session with LaCivitta in Tirana: For Great Albania

2025-05-08 18:40:18

Source: DASH decision a personal victory for Berisha

2025-05-08 18:30:10

Take off those crazy glasses and see where you've taken him?

2025-05-08 18:02:47

LDK files criminal charges against members of the incumbent Government

2025-05-08 18:02:00

BIRN analysis: Tirana, the determining district for the future majority

2025-05-08 16:04:03

Chris LaCivita's contract with the DP, Berisha: 100% correct and clean

2025-05-08 15:11:11

"These are the peak days", Berisha reveals when he will travel to the USA

2025-05-08 14:45:25

Endless boxes with filled-in ballots, DP demands separation of votes from Greece

2025-05-08 14:11:12

Photo/ Who are the 3 associates of Talo Çela arrested in Dubai?

2025-05-08 13:37:09

Hetimi për krimet zgjedhore, Altin Dumani zbarkon në Prokurorinë e Shkodrës

2025-05-08 13:06:21

DASH paves the way for Berisha, Alizoti: Great news on the eve of Great Albania!

2025-05-08 13:03:48

"Freedom works", DP welcomes the US position

2025-05-08 12:48:07

Black smoke rises from the Sistine Chapel, the Vatican still without a Pope

2025-05-08 12:26:18

Davide Pecorrelli extradited to Albania

2025-05-08 11:29:04

'May 11, Albania will react', Xhaferri: Electoral criminals will pay

2025-05-08 11:21:46

Gjin Gjoni: Non Grata fell, Rama should get ready to go to McGonigal

2025-05-08 11:01:54

May 8th deadline for immigrants to vote in Greece extended by one day

2025-05-08 10:48:42

Collapse of massive chrome structure, still no trace of 29-year-old

2025-05-08 10:40:04

Vehicle bursts into flames in Paris Commune

2025-05-08 10:25:43

He gave land to his father and cousin, Basir Çollaku denounces the SP candidate

2025-05-08 10:16:16

Electoral Crimes/ BKH agents and Police conduct checks in Shkodra

2025-05-08 09:19:13

3 associates of Talo Çela arrested in Dubai

2025-05-08 09:02:28

Mouse in the owl's claws, Chris LaCivita responds directly to Rama

2025-05-08 08:45:40

Foreign exchange, how much foreign currencies are sold and bought today

2025-05-08 08:30:38

BIRN: Organized crime, the 'invisible party' of the Durrës elections

2025-05-08 08:26:35

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-05-08 08:08:15

Cloudy and rainy, what the weather is expected to be like throughout the day

2025-05-08 07:52:13

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

2025-05-08 07:40:16

Rama attacks Bardhi: Fier cannot be represented by the world's gas

2025-05-07 22:36:22

EU calls on Israel to lift humanitarian blockade in Gaza

2025-05-07 21:42:34

"Russia is "asking for a lot"! Vance calls for direct Moscow-Kiev talks

2025-05-07 21:20:16

Bank of Albania sets limits on home loans, Sejko: The maximum will be 85%

2025-05-07 20:16:10

EP calls for immediate lifting of measures against Kosovo

2025-05-07 19:39:58