Flash News

Flash News

Gunfire in Durres, a 30-year-old man is injured

Accident on Arbri Street, car goes off the road, two injured

Arrests of "Bankers Petrolium", Prosecution provides details: Exported and sold 532 billion lek of oil, caused millions of euros in damage to the state

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

DW analysis: Why was the Greek-Albanian relationship strained? Threats and mutual distrust

Altin Meshini is a successful producer of organic cheese in Përmet in South Albania. His milk shop is a real tourist attraction: Housed in a large bunker built by Mussolini's Fascist Italy in 1939, it was used by Italian soldiers during the Greco-Italian War of 1940–41 to shell trenches of the Greek Army.

At that time, Albania was occupied by Italy. After the Greek army drove the Italians back to Albania, bloody battles took place around Përmet.

According to the Greek embassy in Tirana, about 8,000 Greek soldiers fell in Albania during the Greco-Italian War, of which 1,300 are buried in Albanian cemeteries.

For Altin Meshini, conveying the memories of the war is an important step towards understanding the preciousness of life and peace. "Look at my dairy," he told DW, "it was built to take life in an absurd war; I use it to nourish life in peacetime."

The past looms large

Unfortunately, the past keeps coming back to haunt contemporary Greek-Albanian relations.

A number of issues currently straining bilateral relations between the two countries have their roots in the past, including a dispute over the delimitation of maritime zones, Greece's Law of War with Albania and the property rights of the Greek minority in Albania.

Greece and Albania are technically still at war

Greece passed the Law of War with Albania in October 1940 after Mussolini's Italy attacked the country from occupied Albania.

Although Albania and Greece signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, Good Neighborliness and Security in 1996, the two NATO allies are, technically, still in a state of war.

According to a representative of the Greek Foreign Ministry, the Greek government agreed in 1987 to repeal the law. However, the Greek parliament has not yet ratified that decision.

The law has long been a source of tension between the two countries, and Albania attaches great importance to its repeal, among other issues related to Greece's past seizure of property belonging to the Albanian state and Albanian nationals. Greek. .

Mayoral elections cause international divisions

Another bone of contention between the two countries is the case of Fredi Beleri, a 52-year-old from the Greek minority in Albania, who was elected mayor of the Albanian municipality of Himara on May 14.

Beleri has not yet been sworn in as mayor of Himara, which has a sizeable Greek community, because he was in custody at the time of the election.

Beleri u arrestua dy ditë para votimit me akuzën e blerjes së votave – akuza që ai i mohon ashpër. Të gjitha kërkesat e tij për lirim ose për t'u lejuar të marrë detyrën janë hedhur poshtë nga gjykatat shqiptare.

A janë të drejtat pronësore të minoritetit grek në qendër të çështjes Beleri?

Vendndodhja e Himarës në bregdetin piktoresk të Jonit të Shqipërisë dhe potenciali i saj si një vend turistik duket të jenë të rëndësishme për rastin.

“Shumë prona në bregdetin e Jonit i përkasin grekëve etnikë, të cilët jetojnë në fshatrat turistike të Himarës”, thotë Skerdian Dhuli, avokat në Himarë. “Megjithatë, për një sërë arsyesh – mbi të gjitha korrupsioni në institucionet publike që merren me pronat – pronarët vendas nuk mund të investojnë në pronat e tyre”.

Pronarët e pronave lokale po humbasin

E njëjta gjë vlen edhe për pronarët e pronave vendase shqiptare, të cilët nuk lejohen të investojnë në sektorin e turizmit as në tokën e tyre. Pronarët e pronave vendase “nuk kanë akses në Këshillin Kombëtar të Territorit, i cili drejtohet nga kryeministri Rama dhe ka autoritetin ligjor për të dhënë leje zhvillimi për bregdetin shqiptar, bazuar në Ligjin për Investimet Strategjike”, thotë Dhuli, i cili sheh. Ligji si një mënyrë “për të grabitur dhe tjetërsuar pronat e pronarëve vendas”.

Sipas Dhulit, ka të dhëna zyrtare për rreth 4000 “prona të mbivendosura” në Himarë. Këto "prona të mbivendosura" janë në pronësi jo vetëm nga pronarët e vërtetë, por edhe nga njerëz që nuk kanë lidhje me pronat, por janë "investitorë strategjikë, të përcaktuar nga qeveria, të cilët investojnë në pronat e vendasve, pronarë realë në Himarë”, tha ai për DW.

Sipas Dhulit, Fredi Beleri, i cili ishte kandidati i opozitës në zgjedhjet për kryebashkiak të Himarës, kishte “premtuar ndryshimin e kësaj situate”.

Greqia kërcënon të bllokojë ofertën e Shqipërisë për anëtarësim në BE

Greqia ka reaguar ashpër ndaj arrestimit dhe burgosjes së Belerit, duke akuzuar Shqipërinë për shkelje të shtetit ligjor dhe të drejtave të minoritetit grek. Athina pretendon se ndalimi i tij është i motivuar politikisht dhe ka thënë se "pret që Shqipëria të marrë masa konkrete dhe të menjëhershme për të lejuar zotin Beleri të bëjë betimin e kryetarit të bashkisë dhe të respektojë të drejtën e tij për një gjykim të drejtë dhe prezumimin e pafajësisë".

Në mesin e nëntorit, Greqia refuzoi të mbështeste një letër që i kërkonte Komisionit Evropian të hapte pesë kapitujt e parë të negociatave për procesin e pranimit të Shqipërisë në BE. Letra u dërgua në fund, por me rezerva greke.

Greqia ka fuqi të konsiderueshme në këtë çështje, sepse vendet anëtare të BE-së duhet të bien dakord unanimisht për hapjen e negociatave të anëtarësimit me një vend. Një veto greke do të bllokonte rrugën e Shqipërisë drejt anëtarësimit në BE.

Mosbesimi i ndërsjellë

According to journalist and writer Stavros Tzimas, mutual mistrust plays a very large role in Greece-Albania relations: "Since the years of the communist dictator [Enver] Hoxha, when the country was isolated, a feeling of being surrounded by the enemy has prevailed in in political, historical and journalistic circles there is a constant suspicion that Greece intends to cripple Albania", he told DW.

"There are also doubts from the Greek side - although the Greek public opinion is not particularly concerned about what is happening in Albania," he says.

Large Albanian community in Greece

Tzimas points out that on the issue of the Greek minority in Albania, mistakes were made on both sides – especially 30 years ago in the direct aftermath of the Hoxha era, when communism collapsed in Eastern Europe.

The ensuing violence between the two communities and the fact that nationalists in Greece referred to a part of southern Albania as "Northern Epirus" damaged relations in the long term. Because of this and the crippling poverty in the country, many members of Albania's Greek minority left.

About 600 thousand Albanians went to Greece. At least half of them stayed, working hard to give their children a better life. These children are now an integral part of Greek society and its future.

Back at the organic bunker milk shop in Përmet, Altin Meshini looks to the future: "Many Italians and Greeks come every year, attracted by the unusual history of the bunker," he says. "When we talk about the past, we all agree that we want to live in peace and have good neighborly relations. We want the past to remain in history and not cloud our present and future."/ DW

Latest news

Greece imposes fee to visit Santorini, how many euros tourists must pay

2025-07-03 20:50:37

Don't make fun of the highlanders, Elisa!

2025-07-03 20:43:43

Gunfire in Durres, a 30-year-old man is injured

2025-07-03 20:30:52

The recount in Fier cast doubt on the integrity of the vote

2025-07-03 20:09:03

Heatwave has left at least 9 dead this week in Europe

2025-07-03 19:00:01

Oil exploitation, Bankers accused of 20-year fraud scheme

2025-07-03 18:33:52

Three drinks that make you sweat less in the summer

2025-07-03 18:19:35

What we know so far about the deaths of Diogo Jota and his brother André Silva

2025-07-03 18:01:56

Another heat wave is expected to grip Europe

2025-07-03 17:10:58

Accident on Arbri Street, car goes off the road, two injured

2025-07-03 16:45:27

Accused of two murders, England says "NO" to Ilirjan Zeqaj's extradition

2025-07-03 16:25:05

Gaza rescue teams: Israeli forces killed 25 people, 12 in shelters

2025-07-03 15:08:43

Diddy's trial ends, producer denied bail

2025-07-03 15:02:41

Agricultural production costs are rising rapidly, 4.8% in 2024

2025-07-03 14:55:13

Warning signs of poor blood circulation

2025-07-03 14:49:47

Croatia recommends its citizens not to travel to Serbia

2025-07-03 14:31:19

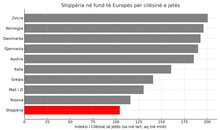

Berisha: Albania is the blackest stain in Europe for the export of emigrants

2025-07-03 14:20:19

'Ministry of Smoke': Activists Blame Government for Wasteland Fires

2025-07-03 13:59:09

AFF message of condolences for the tragic loss of Diogo Jota and his brother

2025-07-03 13:41:36

Five healthy foods you should add to your diet

2025-07-03 13:30:19

A unique summer season, full of rhythm and rewards for Credins bank customers!

2025-07-03 12:12:20

Fire situation in the country, 29 fires reported in 24 hours

2025-07-03 12:00:04

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 41st time

2025-07-03 11:59:57

The gendering of politics

2025-07-03 11:48:36

The price we pay after the "elections"

2025-07-03 11:25:39

Xhafa: The fire at the Elbasan landfill was deliberately lit to destroy evidence

2025-07-03 11:08:43

The 3 zodiac signs that will have financial growth during July

2025-07-03 10:48:01

Democratic MP talks about the incinerator, Spiropali turns off her microphone

2025-07-03 10:39:24

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

2025-07-03 10:21:03

Cocaine trafficking network in Greece, including Albanians, uncovered

2025-07-03 10:10:12

Korreshi: Election manipulation began long before the voting date

2025-07-03 09:39:13

Arrest of Greek customs officer 'paralyzes' vehicle traffic at Qafë Botë

2025-07-03 09:28:41

After Tirana and Fier, the boxes are opened in Durrës today

2025-07-03 09:21:10

Enea Mihaj transfers to the USA, will play as an opponent of Messi and Uzun

2025-07-03 09:10:04

Foreign exchange, the rate at which foreign currencies are sold and bought

2025-07-03 08:53:50

Index, Albania has the worst quality of life in Europe

2025-07-03 08:48:10

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-07-03 08:17:05

Clear weather and high temperatures, here's the forecast for this Thursday

2025-07-03 08:00:37

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

2025-07-03 07:46:48

Lufta në Gaza/ Pse Netanyahu do vetëm një armëpushim 60-ditor, jo të përhershëm?

2025-07-02 21:56:08

US suspends some military aid to Ukraine

2025-07-02 21:40:55

Methadone shortage, users return to heroin: We steal to buy it

2025-07-02 20:57:35

Government enters oil market, Rama: New price for consumers

2025-07-02 20:43:30

WHO calls for 50% price hike for tobacco, alcohol and sugary drinks

2025-07-02 20:41:53