Flash News

Flash News

Gunfire in Durres, a 30-year-old man is injured

Accident on Arbri Street, car goes off the road, two injured

Arrests of "Bankers Petrolium", Prosecution provides details: Exported and sold 532 billion lek of oil, caused millions of euros in damage to the state

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

"Der Standard": Albanian farmers protest against bankruptcy, remain unintegrated in the EU market

Oil. Milk. The blood. Everything comes together when farmers in the north of Albania talk about their lives. Oil is expensive, more expensive than in neighboring countries such as Montenegro or Serbia. But the more expensive oil is, the more expensive milk production becomes. Compared to Europe, the price of one liter of milk produced by Albanian farmers is therefore extremely high.

Farmers are sometimes left with their expensive milk because dairies prefer to import cheaper milk from the EU or Serbia. In April, a farmer spilled ten thousand liters on the road near Fier, in the heart of the country. It flowed in white streams among the protesting farmers. The farmer said of his protest: "Everyone can see how unfair the prices are! Milk is the lifeblood of the farmer!" In fact, many farmers in Albania are going bankrupt.

Gezim Doda from the Lezha District in northern Albania, a man with calluses on his hands, wearing jeans and a light blue T-shirt, fears that he too will have to be locked up. It has recently applied for oil subsidies. Until spring, dairies paid 80 Lek per liter, now it is only 75 Lek, equivalent to about 75 cents. Both in Serbia and in the EU, dairy farmers are subsidized much more than in Albania.

Low demand

Until now, each farmer received 85 euros per cow per year for a maximum of 50 cows. From this year, farmers also receive money for additional cows, but only 43 euros. That's why farmers want to see subsidies per liter of milk in the future, like in the EU. Especially in the spring, when cows produce more milk, they often do not find buyers. "How do I explain to my cow that she needs to produce less milk?" asks Mr. Doda, looking into the large eyes, surrounded by beautiful eyelashes, of one of the cows chewing behind the metal bars. Doda likes his cows. "They feed us, we get along better with them than with humans," he explains. "Even though you can't talk to them, they comfort you!" he is convinced.

His stable sits over the River Mat, which is spanned by a crooked concrete bridge you wouldn't want to drive over. The view extends over the river landscape with wide gravel banks. The 48-year-old, father of three children, has saved money in Great Britain to buy about 100 cows in Albania. "If I was only twenty, I would have gone bankrupt a long time ago" , he explains the market conditions.

In recent years, more and more people have emigrated from the north of Albania, because they cannot make a living from their small farms. Villages are half empty and often only old people are left. A year ago, the EU also suspended IPARD agricultural funds for Albania due to corruption cases.

The tradition of resistance

As everywhere in Europe, Albanian farmers have lost social and political influence. According to the Institute of Statistics, the agricultural sector, although it still employs a third of all workers here, shrank by more than three percent last year. It is a rapid decline. Farmer Doda still wants to keep fighting before he has to sell his cows. He is even prepared to take to the streets to do so.

Albanian farmers were already famous for their endurance in the early 20th century. The uprising of the peasants of Central Albania - named after its leader Haxhi Qamili - in 1914 and 1915 was not only about prizes, but above all about political resistance against Prince Wilhelm zu Wied, who had been appointed by the great European powers and who then became afraid. Weed left the country in 1915 because he and his Dutch gendarmes could only control a few kilometers around the port city of Durrës. The farmers had taken control.

At that time they wanted to return to Ottoman rule. In fact, there were few peasant uprisings in the Ottoman Empire compared to Central Europe. American sociologist Karen Barkey attributes this to the timar system: the most cultivated land was divided into districts, the owners of which were called timariots. The peasants had to pay taxes to them, but they were not directly dependent on them, and they could communicate with the central government in Constantinople through emissaries from their own communities - called bekiles.

Only partially competitive

Today, farmers in the Western Balkans, who are not integrated into the EU market, are only very limited competitive. Many of those still working in the agricultural sector will be gone in a few years. The villages in Albania will be emptied even more, many fields will remain barren. Therefore, some are using the land for an agricultural product that cannot be officially traded: cannabis.

Just a week ago, two men were arrested near Vlora, while they were guarding their 320 plants hidden in an olive grove at night. Illegal hemp plantations are seen by some as a modern form of peasant uprising, a rebellion against expensive oil and EU agricultural subsidies that cannot be kept up.

Latest news

Greece imposes fee to visit Santorini, how many euros tourists must pay

2025-07-03 20:50:37

Don't make fun of the highlanders, Elisa!

2025-07-03 20:43:43

Gunfire in Durres, a 30-year-old man is injured

2025-07-03 20:30:52

The recount in Fier cast doubt on the integrity of the vote

2025-07-03 20:09:03

Heatwave has left at least 9 dead this week in Europe

2025-07-03 19:00:01

Oil exploitation, Bankers accused of 20-year fraud scheme

2025-07-03 18:33:52

Three drinks that make you sweat less in the summer

2025-07-03 18:19:35

What we know so far about the deaths of Diogo Jota and his brother André Silva

2025-07-03 18:01:56

Another heat wave is expected to grip Europe

2025-07-03 17:10:58

Accident on Arbri Street, car goes off the road, two injured

2025-07-03 16:45:27

Accused of two murders, England says "NO" to Ilirjan Zeqaj's extradition

2025-07-03 16:25:05

Gaza rescue teams: Israeli forces killed 25 people, 12 in shelters

2025-07-03 15:08:43

Diddy's trial ends, producer denied bail

2025-07-03 15:02:41

Agricultural production costs are rising rapidly, 4.8% in 2024

2025-07-03 14:55:13

Warning signs of poor blood circulation

2025-07-03 14:49:47

Croatia recommends its citizens not to travel to Serbia

2025-07-03 14:31:19

Berisha: Albania is the blackest stain in Europe for the export of emigrants

2025-07-03 14:20:19

'Ministry of Smoke': Activists Blame Government for Wasteland Fires

2025-07-03 13:59:09

AFF message of condolences for the tragic loss of Diogo Jota and his brother

2025-07-03 13:41:36

Five healthy foods you should add to your diet

2025-07-03 13:30:19

A unique summer season, full of rhythm and rewards for Credins bank customers!

2025-07-03 12:12:20

Fire situation in the country, 29 fires reported in 24 hours

2025-07-03 12:00:04

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 41st time

2025-07-03 11:59:57

The gendering of politics

2025-07-03 11:48:36

The price we pay after the "elections"

2025-07-03 11:25:39

Xhafa: The fire at the Elbasan landfill was deliberately lit to destroy evidence

2025-07-03 11:08:43

The 3 zodiac signs that will have financial growth during July

2025-07-03 10:48:01

Democratic MP talks about the incinerator, Spiropali turns off her microphone

2025-07-03 10:39:24

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

2025-07-03 10:21:03

Cocaine trafficking network in Greece, including Albanians, uncovered

2025-07-03 10:10:12

Korreshi: Election manipulation began long before the voting date

2025-07-03 09:39:13

Arrest of Greek customs officer 'paralyzes' vehicle traffic at Qafë Botë

2025-07-03 09:28:41

After Tirana and Fier, the boxes are opened in Durrës today

2025-07-03 09:21:10

Enea Mihaj transfers to the USA, will play as an opponent of Messi and Uzun

2025-07-03 09:10:04

Foreign exchange, the rate at which foreign currencies are sold and bought

2025-07-03 08:53:50

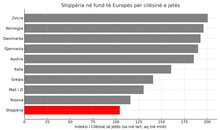

Index, Albania has the worst quality of life in Europe

2025-07-03 08:48:10

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-07-03 08:17:05

Clear weather and high temperatures, here's the forecast for this Thursday

2025-07-03 08:00:37

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

2025-07-03 07:46:48

Lufta në Gaza/ Pse Netanyahu do vetëm një armëpushim 60-ditor, jo të përhershëm?

2025-07-02 21:56:08

US suspends some military aid to Ukraine

2025-07-02 21:40:55

Methadone shortage, users return to heroin: We steal to buy it

2025-07-02 20:57:35

Government enters oil market, Rama: New price for consumers

2025-07-02 20:43:30

WHO calls for 50% price hike for tobacco, alcohol and sugary drinks

2025-07-02 20:41:53