Flash News

Flash News

Accident at "Shkalla e Tujanit", truck overturns in the middle of the road, driver injured

Vlora by-pass, work delays and cost increases

Milan are expected to give up on the transfer of Granit Xhaka

Inceneratori jashtë funksionit, përfshihet nga flakët fusha e mbetjeve në Elbasan

Accident on the Lezhë-Shëngjin axis, one injured

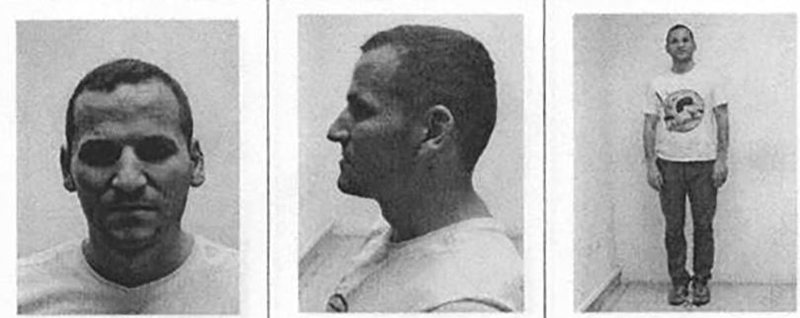

In the footsteps of the Albanian Narcos Dritan Rexhepi, the king of cocaine

By James Marson and Giovanni Legorano

FLORENCE, Italy—Police here say they traced a sprawling network flooding Europe with cocaine to an unlikely kingpin: an Albanian hit man incarcerated in Ecuador.

The yearslong operation exposed how new criminal groups are taking advantage of globalization to turn Europe into a rival of the U.S. as the biggest market for cocaine, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

Police say the Albanian, Dritan Rexhepi, sourced cocaine from Colombia from a fellow inmate. Using a concealed cellphone, he arranged shipments worth hundreds of millions of dollars on container ships to ports in the Netherlands, transferred the proceeds and ordered attacks on adversaries, including two murders, according to Italian officials.

Prison authorities in Ecuador said inmates don’t have access to cellphones. In practice, authorities regularly announce that they have confiscated phones, drugs and guns from prisoners.

This account of the rise and fall of Mr. Rexhepi’s group is based on interviews with a half-dozen Italian and other European law-enforcement officials, and Italian court documents.

The operation that snared Mr. Rexhepi began with a vice bust in Florence in April 2014.

Police detained several Albanians brawling over the prostitution business, and further investigation uncovered potential links with drug trafficking.

During an apartment search, police discovered a BlackBerry that contained 10 PINs, codes associated with other devices but with no names or telephone numbers to identify their owners.

A judge ordered BlackBerry Ltd. to provide access to the encrypted messages of the one PIN that was still active. The messages revealed that a group of Albanians was bringing cocaine from the Netherlands to supply a powerful criminal group in southern Italy.

“This is when we realized they must be a big organization with its own market,” says Ms. Del Prete, a 33-year police veteran accustomed to tussling mostly with local pimps and drug peddlers.

Police gained access to more PINs as other countries joined the investigation, revealing that the Albanians were using the Netherlands as a hub to distribute cocaine across Europe.

Ms. Del Prete and four colleagues plowed through messages from across the world arriving almost in real time.

Her team created dummy accounts on social networks to monitor profiles of ostentatious suspects, using “likes” and comments on photos to match them up to BlackBerry accounts.

By 2016, they knew the kingpin was in Ecuador, but couldn’t identify him. Then, odd clues popped out of his chats.

“I’m going for my outdoor time,” he wrote in one message. “I need to hide my phone,” he said in another.

When, in a further conversation, he mentioned a conviction, Ms. Del Prete says it clicked that he was behind bars, and police soon identified Mr. Rexhepi.

Mr. Rexhepi was shaped by the economic strife and criminal violence that gripped Albania in the 1990s as it emerged from Communist rule.

In 1999, while still a teenager, he carried out a contract hit on a policeman in a bar, spraying him with bullets from a Kalashnikov rifle that also killed another man, according to Arben Frasheri, a former senior Albanian prosecutor.

Police only arrested Mr. Rexhepi in January 2006 in the capital, Tirana.

That same evening, Mr. Rexhepi escaped from an interrogation room after opening a defective lock with his finger and telling a guard the police were done with him. A court later convicted him in absentia of murder.

That was the first of three jailbreaks as European police pursued him across the continent on drug-trafficking and other charges. In Italy, he sawed through the bars of his cell and lowered himself to freedom. In Belgium, he escaped by climbing over a wall.

An Albanian reporter last year published what he said was an interview with Mr. Rexhepi, in which the convict said false murder charges had caused him to flee the country, precluded securing a legitimate job in Western Europe and forced him into a life of drug crime.

“Survival instinct led me in that direction,” he was quoted as saying.

The next time police nabbed him was in Ecuador in June 2014, where he was caught in possession of more than 600 pounds of cocaine, according to Interpol, the international police organization.

In jail there, Mr. Rexhepi allied with an Ecuadorean drug trafficker with links to powerful cartels in Colombia and Mexico.

Cocaine was dispatched across the Atlantic on container ships, mostly to ports in the Netherlands, where one gang member had corrupt connections. Around 110 pounds of cocaine a day would be brought ashore, whisked to storage and processing centers, then transported to Italy and other markets using double-bottomed cars.

Mr. Rexhepi had at his direct orders a number of Albanians in Ecuador, the Netherlands, Italy and Albania and business partners in most of Western Europe who controlled channels of cocaine distribution across the continent.

As Mr. Rexhepi’s group expanded, it sought to stand out.

“Let’s get into the market with our own name,” the group’s coordinator in Italy wrote Mr. Rexhepi in March 2016. “Our brand is still not known.”

Mr. Rexhepi wrote back, proposing the name Bello, or Beautiful. The group’s bricks of cocaine were soon stamped with the brand.

Mr. Rexhepi ruled Kompania Bello with charisma and violence. He ordered assaults and at least two murders, one in Ecuador and one in Albania, according to Italian police. Arrested associates refused to talk, citing fear of retaliation against their families, Ms. Del Prete says.

Albanians in trouble turned to him for help. When Mr. Rexhepi found out three compatriots escaped from a Rome jail at 3 a.m. one day in late 2016, he arranged for a dinghy to pick them up on Italy’s southern coast to take them to Albania.

Mr. Rexhepi moved cash across the Atlantic using the Chinese feiqian, or flying money, system, where money deposited with an agent in one country can be withdrawn from another in a different country, largely without leaving a paper trail. He also saved money on commission by using his own couriers. In June 2016, Florence police tipped off Ecuadorean colleagues, who intercepted a courier at Guayaquil airport with €350,000, equivalent to around $392,000, stashed in the lining of a suitcase.

Ms. Del Prete’s team celebrated every seizure of money and cocaine with a bottle of Prosecco or Greek brandy. Some 20 bottles now line the top of a cupboard in her small office.

“It was a big test for us,” she says. “We had not done anything like this before here in Florence.”

Latest news

Golem and Qerret without water at the peak of the tourist season

2025-07-01 21:09:32

Euractiv: Italy-Albania migrant deal faces biggest legal challenge yet

2025-07-01 20:53:38

BIRN: Brataj and Fevziu victims of a 'deepfake' on Facebook

2025-07-01 20:44:00

Vlora by-pass, work delays and cost increases

2025-07-01 20:24:29

Milan are expected to give up on the transfer of Granit Xhaka

2025-07-01 19:41:25

The silent but rapid fading of the towers' euphoria

2025-07-01 18:58:07

Donald Trump's daughter says 'goodbye' to June with photos from Vlora

2025-07-01 18:48:47

Tirana vote recount, Alimehmeti: CEC defended manipulation

2025-07-01 18:15:05

Left Flamurtari, striker signs with another Albanian club

2025-07-01 17:43:14

Accident on the Lezhë-Shëngjin axis, one injured

2025-07-01 17:19:35

June temperature records, Italy limits outdoor work

2025-07-01 17:03:15

Meet Kozeta Miliku, named one of the top five scientists in Canada

2025-07-01 16:32:12

"Arsonist" arrested for repeatedly setting fires in Vlora (NAME)

2025-07-01 16:29:45

The ecological integrity of the Vjosa River risks remaining on paper

2025-07-01 16:09:40

Heat Headache/ Causes, Symptoms and Measures You Should Take

2025-07-01 16:01:13

UN: The world must learn to live with heat waves

2025-07-01 15:54:50

Three cars collide in Tirana, one of them catches fire

2025-07-01 15:38:16

Shehu: Whoever doesn't want Berisha, doesn't want the opposition 'war'!

2025-07-01 15:19:20

Berisha requests the OSCE Assembly: Help my nation vote freely

2025-07-01 15:11:46

Be careful with medications: Some of them can harm your sex life

2025-07-01 15:00:32

'Golden Bullet'/ Lawyers leave the courtroom, Altin Ndoc's trial postponed again

2025-07-01 14:44:52

EU changes leadership, Kosovo in a number of places

2025-07-01 14:40:01

Should we drink a lot of water? Experts are surprised: You risk hyponatremia

2025-07-01 14:30:20

Lëpusha beyond Rama's postcards: A village that is being silently abandoned

2025-07-01 13:41:56

Scorching temperatures in France close the Eiffel Tower

2025-07-01 13:29:35

Media: China, Iran and North Korea, a threat to European security

2025-07-01 13:20:12

Albania drops in global index: Less calm, more insecure

2025-07-01 13:09:35

Road collapses, 5 villages in Martanesh risk being isolated

2025-07-01 13:03:04

Këlliçi: Opposition action to be decided in September

2025-07-01 12:48:49

Four tips for coping with the heat wave

2025-07-01 12:38:53

Car hits pedestrian on Transbalkan road

2025-07-01 12:27:09

Authors of 9 robberies, Erjon Sopoti and Abdullah Zyberi arrested

2025-07-01 12:15:56

He abused his minor daughter, this is a 36-year-old man in custody in Fier

2025-07-01 11:50:34

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 40th time

2025-07-01 11:40:08

EU confirms support for the Western Balkans

2025-07-01 10:50:45

Serious in Fier! Father sexually abuses his minor daughter

2025-07-01 10:32:33

One year since the passing of the colossus of Albanian literature, Ismail Kadare

2025-07-01 10:25:26

They supplied the 'spaçators' with drugs, two young men are arrested in Tirana

2025-07-01 09:54:09

Europe is "scorching", how dangerous are high temperatures?

2025-07-01 09:48:56

Nigel Farage in Albania: but why?

2025-07-01 09:13:12

Xama: The "Partizani" dossier is quite weak and without facts!

2025-07-01 09:04:47

Foreign exchange, the rate at which foreign currencies are sold and bought

2025-07-01 08:35:39

Fabricators again warn of factory closures and job cuts

2025-07-01 08:21:30

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-07-01 08:08:59

Scorching hot, temperatures reaching 40°C

2025-07-01 07:57:12

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-07-01 07:42:59

Recount after May 11, Braho: I had no expectations for massive vote trafficking

2025-06-30 22:54:18

Second hearing on the protected areas law, Zhupa: Unconstitutional and dangerous

2025-06-30 22:18:46

Israel-Iran conflict, Bushati: Albanians should be concerned

2025-06-30 21:32:42

Fuga: Journalism in Albania today in severe crisis

2025-06-30 21:07:11

"There is no room for panic"/ Moore: Serbia does not dare to attack Kosovo!

2025-06-30 20:49:53

Temperatures above 40 degrees, France closes nuclear plants and schools

2025-06-30 20:28:42

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

2025-06-30 20:13:54

Turkey against the "Bektashi state" in Albania: Give up this idea!

2025-06-30 20:03:24

Accused of sexual abuse, producer Diddy awaits court decision

2025-06-30 19:40:44