Flash News

Flash News

Gunfire in Durres, a 30-year-old man is injured

Accident on Arbri Street, car goes off the road, two injured

Arrests of "Bankers Petrolium", Prosecution provides details: Exported and sold 532 billion lek of oil, caused millions of euros in damage to the state

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

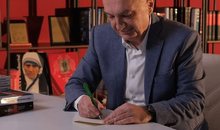

Alfred Lela

The subsequent scandals—they have become so numerous that it is hard to count them —revealed the same systemic problem in the government and the largest municipality in the country, led by Erion Veliaj.

A dozen high-ranking directors, clustered around a private-municipal 'corporation' named 5D, served as manipulators of dubious activities in Tirana's government.

For comparison, it can be said that, as the government fell after the corruption of some ministers, the municipality also fell, precisely through the fall of its 'ministers,' senior directors.

All this is bringing back, for the seventh time in the public discourse, the attitude of the government and the municipality, baptized in the famous writings as justicialismo. In summary, this term marks the exchange of political governance after its decline, even if symbolic, with a new type of governance where justice takes over with its apparatus of prosecutors-courts.

When you heard Mayor Veliaj's face, finally, the public pressure against the involvement of close collaborators in suspected corruption, this 'handover' of the public's keys to a body that Albanians do not vote for, justice, turned a blind eye.

If you were to concentrate Rama and Veliaj's speech in a short phrase, it would be 'we steal, but justice is strong'.

This is, therefore, judicialism and it is hazardous.

First, because it does not perform what parliamentary democracies are based on, the separation of powers, but superimposes one power against another, according to the moment's needs. In this case, the executive is happy to govern without interruption, releasing some of its exponents into the throats of justice. This looks like a claim by the public - they steal but are also punished - but what does not produce is responsibility. Where is the political responsibility in this case? Who holds it? Who reflects?

Secondly, politics, through the government and the municipality, cannot present justice as a shield to the Albanian voters. It is as if for nothing else because in Albania, unlike in America, there is no direct vote for prosecutors and judges. So, the governing Pontius Pilate does not wash his hands, saying that the Jewish juridical body solves the punishment of Christ and that it is not a matter of political Rome but the work of bandits and courts.

This is done to strip the government/municipality of its responsibilities and shift the public debate towards "Christ or Barabbas?" type questions. In the end, Barabbas is saved, although there is no Christ in this game of ours.

It should be added that this new illegitimate state based on justicialismo suits the new justice, if only for the banal fact that it motivates them to demand salary increases and other benefits from the government (as they have done). Without forgetting their idealization through polls that heroize them and help the government.

This Mephistophelian pact between the government and justice allowed an ad hoc justicialismo to undo the state-building efforts of 32 years of several governments. The executive cannot hide behind the judiciary nor resolve political crises through it. The judiciary cannot play the role of the armor of the government, guarding its leaders and rolling 'scapegoats.' Whoever heads the political campaigns must bear the burden of guilt for the team he builds and chooses to govern after the victory.

The introduction of justice between this democratic axiom, the public, and its interests is nothing less than the legal body that executes Christ and puts Barabbas into circulation (Christ, in this case, is a just system of the legal and democratic state).

Latest news

Greece imposes fee to visit Santorini, how many euros tourists must pay

2025-07-03 20:50:37

Don't make fun of the highlanders, Elisa!

2025-07-03 20:43:43

Gunfire in Durres, a 30-year-old man is injured

2025-07-03 20:30:52

The recount in Fier cast doubt on the integrity of the vote

2025-07-03 20:09:03

Heatwave has left at least 9 dead this week in Europe

2025-07-03 19:00:01

Oil exploitation, Bankers accused of 20-year fraud scheme

2025-07-03 18:33:52

Three drinks that make you sweat less in the summer

2025-07-03 18:19:35

What we know so far about the deaths of Diogo Jota and his brother André Silva

2025-07-03 18:01:56

Another heat wave is expected to grip Europe

2025-07-03 17:10:58

Accident on Arbri Street, car goes off the road, two injured

2025-07-03 16:45:27

Accused of two murders, England says "NO" to Ilirjan Zeqaj's extradition

2025-07-03 16:25:05

Gaza rescue teams: Israeli forces killed 25 people, 12 in shelters

2025-07-03 15:08:43

Diddy's trial ends, producer denied bail

2025-07-03 15:02:41

Agricultural production costs are rising rapidly, 4.8% in 2024

2025-07-03 14:55:13

Warning signs of poor blood circulation

2025-07-03 14:49:47

Croatia recommends its citizens not to travel to Serbia

2025-07-03 14:31:19

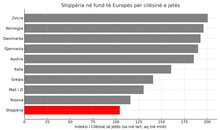

Berisha: Albania is the blackest stain in Europe for the export of emigrants

2025-07-03 14:20:19

'Ministry of Smoke': Activists Blame Government for Wasteland Fires

2025-07-03 13:59:09

AFF message of condolences for the tragic loss of Diogo Jota and his brother

2025-07-03 13:41:36

Five healthy foods you should add to your diet

2025-07-03 13:30:19

A unique summer season, full of rhythm and rewards for Credins bank customers!

2025-07-03 12:12:20

Fire situation in the country, 29 fires reported in 24 hours

2025-07-03 12:00:04

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 41st time

2025-07-03 11:59:57

The gendering of politics

2025-07-03 11:48:36

The price we pay after the "elections"

2025-07-03 11:25:39

Xhafa: The fire at the Elbasan landfill was deliberately lit to destroy evidence

2025-07-03 11:08:43

The 3 zodiac signs that will have financial growth during July

2025-07-03 10:48:01

Democratic MP talks about the incinerator, Spiropali turns off her microphone

2025-07-03 10:39:24

Ndahet nga jeta tragjikisht në moshën 28-vjeçare ylli i Liverpool, Diogo Jota

2025-07-03 10:21:03

Cocaine trafficking network in Greece, including Albanians, uncovered

2025-07-03 10:10:12

Korreshi: Election manipulation began long before the voting date

2025-07-03 09:39:13

Arrest of Greek customs officer 'paralyzes' vehicle traffic at Qafë Botë

2025-07-03 09:28:41

After Tirana and Fier, the boxes are opened in Durrës today

2025-07-03 09:21:10

Enea Mihaj transfers to the USA, will play as an opponent of Messi and Uzun

2025-07-03 09:10:04

Foreign exchange, the rate at which foreign currencies are sold and bought

2025-07-03 08:53:50

Index, Albania has the worst quality of life in Europe

2025-07-03 08:48:10

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-07-03 08:17:05

Clear weather and high temperatures, here's the forecast for this Thursday

2025-07-03 08:00:37

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

2025-07-03 07:46:48

Lufta në Gaza/ Pse Netanyahu do vetëm një armëpushim 60-ditor, jo të përhershëm?

2025-07-02 21:56:08

US suspends some military aid to Ukraine

2025-07-02 21:40:55

Methadone shortage, users return to heroin: We steal to buy it

2025-07-02 20:57:35

Government enters oil market, Rama: New price for consumers

2025-07-02 20:43:30

WHO calls for 50% price hike for tobacco, alcohol and sugary drinks

2025-07-02 20:41:53