Flash News

Flash News

Accident at "Shkalla e Tujanit", truck overturns in the middle of the road, driver injured

Vlora by-pass, work delays and cost increases

Milan are expected to give up on the transfer of Granit Xhaka

Inceneratori jashtë funksionit, përfshihet nga flakët fusha e mbetjeve në Elbasan

Accident on the Lezhë-Shëngjin axis, one injured

George Will/ The Washington Post

The list of secretaries of state includes many giants of public stature - Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, James Madison, James Monroe, Henry Clay, John Calhoun, Daniel Webster, William Seward, Elihu Root, William Jennings Bryan, Charles Evans Hughes, Edward Stettinius, George Shultz, and James Baker. However, no one brought more style and flair to this office than the first immigrant to the post.

Although Henry Kissinger ranks, with John Quincy Adams, John Hay, and Dean Acheson, among the most intellectually sophisticated and culturally cosmopolitan American secretaries of state, even in his 10th decade, love for this country had an almost childlike purity. This suited him, who had seen Hitler's Germany through the eyes of a child.

Kissinger, who died Wednesday at the age of 100, made America less American by inoculating it with a European sense of life's irredeemably tragic dimension. Yet, as immigrants often are, he was a romantic for the nation that accepted him and allowed him to grow.

Kissinger wove romanticism with cynicism while teaching realism to this nation. What critics called elegant immorality, he considered the granite foundation of true morality—the confrontation with unpleasant and intractable facts. One such is the temporality (impermanence) of permanence (permanence) in the international system.

A consequence of this maxim is the inevitable imperative of power balances. Hence, Kissinger's most outstanding achievement was helping, as Richard Nixon's national security adviser, bring China into the game of nations. Kissinger admired the Chinese as "scientists of balance, artists of relativity." He also admired Charles de Gaulle, "son of a continent covered in ruins," who understood that finality is a chimera: "History knows no resorts and plateaus" because "managing a balance of power is a permanent undertaking, not an endeavor that has a predictable end.”

Kissinger became Secretary in the most eventful year of the post-World War II era, which marked, like a tectonic crash, the creative quarter-century of American diplomacy that began with the Marshall Plan of 1948. In 1973, while the authority of the President faded, and an ephemeral "peace" was concluded in Vietnam, a revolution in energy prices was precipitated by the Yom Kippur War, a crisis on the scale of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the most dangerous moment of the War Cold.

Politics has its physics, and Kissinger's gluttony for power, his sharp elbows in bureaucratic warfare, and his erratic inability to tolerate idiots combined to make him enemies in Washington, which admires few for many. Time. Although he came from the academic world to be a planet revolving around the sun of presidential power, he stayed to become the sun himself. When Nixon, who had put Kissinger on the path to glory, resigned, one of the first decisions of his successor, Gerald Ford, was to reassure an anxious world that Kissinger's hand would remain in foreign policy. By the time Kissinger left office, he had ranked, along with George Marshall, among America's most historic public officials who had never served in elected or judicial office.

Kissinger tempered his strategic pessimism with tactical optimism. He thought that, as a Confederate cavalry officer, he would accumulate time for the West with courage and skill. The Soviet Union, like Gulliver, could be held back by numerous tiny threads of political, arms control, and economic agreements.

Kissinger's pessimism about Western exhaustion arose from two miscalculations. He underestimated the resistance of the bourgeois societies of the West. One reason he was wrong about the resilience of these societies to withstand the course of the Cold War was his overestimation of the economic backbone of the Soviet system.

A decade after Kissinger left the State Department, communism, whose creed derived from the economic determinism of Marxism, learned a brutal, indeed fatal, lesson in the importance of economic factors. 1976 Ronald Reagan challenged Ford for the Republican nomination, running against Kissingerism. And at the 1986 summit in Iceland, Reagan told Mikhail Gorbachev that if there was an intensified arms race, he could guarantee America would win. The statesman's task, Kissinger believed, is "to rescue a predetermined element under the pressure of circumstances." He helped manage the Cold War until the nation elected a president determined not to work but to win the war.

What Andre Malraux said of De Gaulle can be said of Kissinger: Steeped in history, he was "a man of yesterday and the day after tomorrow."

Latest news

Golem and Qerret without water at the peak of the tourist season

2025-07-01 21:09:32

Euractiv: Italy-Albania migrant deal faces biggest legal challenge yet

2025-07-01 20:53:38

BIRN: Brataj and Fevziu victims of a 'deepfake' on Facebook

2025-07-01 20:44:00

Vlora by-pass, work delays and cost increases

2025-07-01 20:24:29

Milan are expected to give up on the transfer of Granit Xhaka

2025-07-01 19:41:25

The silent but rapid fading of the towers' euphoria

2025-07-01 18:58:07

Donald Trump's daughter says 'goodbye' to June with photos from Vlora

2025-07-01 18:48:47

Tirana vote recount, Alimehmeti: CEC defended manipulation

2025-07-01 18:15:05

Left Flamurtari, striker signs with another Albanian club

2025-07-01 17:43:14

Accident on the Lezhë-Shëngjin axis, one injured

2025-07-01 17:19:35

June temperature records, Italy limits outdoor work

2025-07-01 17:03:15

Meet Kozeta Miliku, named one of the top five scientists in Canada

2025-07-01 16:32:12

"Arsonist" arrested for repeatedly setting fires in Vlora (NAME)

2025-07-01 16:29:45

The ecological integrity of the Vjosa River risks remaining on paper

2025-07-01 16:09:40

Heat Headache/ Causes, Symptoms and Measures You Should Take

2025-07-01 16:01:13

UN: The world must learn to live with heat waves

2025-07-01 15:54:50

Three cars collide in Tirana, one of them catches fire

2025-07-01 15:38:16

Shehu: Whoever doesn't want Berisha, doesn't want the opposition 'war'!

2025-07-01 15:19:20

Berisha requests the OSCE Assembly: Help my nation vote freely

2025-07-01 15:11:46

Be careful with medications: Some of them can harm your sex life

2025-07-01 15:00:32

'Golden Bullet'/ Lawyers leave the courtroom, Altin Ndoc's trial postponed again

2025-07-01 14:44:52

EU changes leadership, Kosovo in a number of places

2025-07-01 14:40:01

Should we drink a lot of water? Experts are surprised: You risk hyponatremia

2025-07-01 14:30:20

Lëpusha beyond Rama's postcards: A village that is being silently abandoned

2025-07-01 13:41:56

Scorching temperatures in France close the Eiffel Tower

2025-07-01 13:29:35

Media: China, Iran and North Korea, a threat to European security

2025-07-01 13:20:12

Albania drops in global index: Less calm, more insecure

2025-07-01 13:09:35

Road collapses, 5 villages in Martanesh risk being isolated

2025-07-01 13:03:04

Këlliçi: Opposition action to be decided in September

2025-07-01 12:48:49

Four tips for coping with the heat wave

2025-07-01 12:38:53

Car hits pedestrian on Transbalkan road

2025-07-01 12:27:09

Authors of 9 robberies, Erjon Sopoti and Abdullah Zyberi arrested

2025-07-01 12:15:56

He abused his minor daughter, this is a 36-year-old man in custody in Fier

2025-07-01 11:50:34

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 40th time

2025-07-01 11:40:08

EU confirms support for the Western Balkans

2025-07-01 10:50:45

Serious in Fier! Father sexually abuses his minor daughter

2025-07-01 10:32:33

One year since the passing of the colossus of Albanian literature, Ismail Kadare

2025-07-01 10:25:26

They supplied the 'spaçators' with drugs, two young men are arrested in Tirana

2025-07-01 09:54:09

Europe is "scorching", how dangerous are high temperatures?

2025-07-01 09:48:56

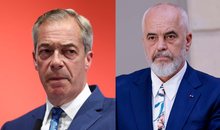

Nigel Farage in Albania: but why?

2025-07-01 09:13:12

Xama: The "Partizani" dossier is quite weak and without facts!

2025-07-01 09:04:47

Foreign exchange, the rate at which foreign currencies are sold and bought

2025-07-01 08:35:39

Fabricators again warn of factory closures and job cuts

2025-07-01 08:21:30

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-07-01 08:08:59

Scorching hot, temperatures reaching 40°C

2025-07-01 07:57:12

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-07-01 07:42:59

Recount after May 11, Braho: I had no expectations for massive vote trafficking

2025-06-30 22:54:18

Second hearing on the protected areas law, Zhupa: Unconstitutional and dangerous

2025-06-30 22:18:46

Israel-Iran conflict, Bushati: Albanians should be concerned

2025-06-30 21:32:42

Fuga: Journalism in Albania today in severe crisis

2025-06-30 21:07:11

"There is no room for panic"/ Moore: Serbia does not dare to attack Kosovo!

2025-06-30 20:49:53

Temperatures above 40 degrees, France closes nuclear plants and schools

2025-06-30 20:28:42

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

2025-06-30 20:13:54

Turkey against the "Bektashi state" in Albania: Give up this idea!

2025-06-30 20:03:24

Accused of sexual abuse, producer Diddy awaits court decision

2025-06-30 19:40:44