Flash News

Flash News

He breaks arrest, steals a car and escapes like in a movie, the serial thief from Tirana is caught!

Name/ She deceived clients and took their money, the lawyer is wanted

Criminal group busted, trafficking dogs from Spain to Finland, the 'heads' of the group were Albanians

She escaped drowning in Durres, the 31-year-old English woman speaks: We capsized instantly, my friend was trapped under the vehicle

Due to lack of lawyers/ The hearing for the 'Golden Bullet' is postponed again

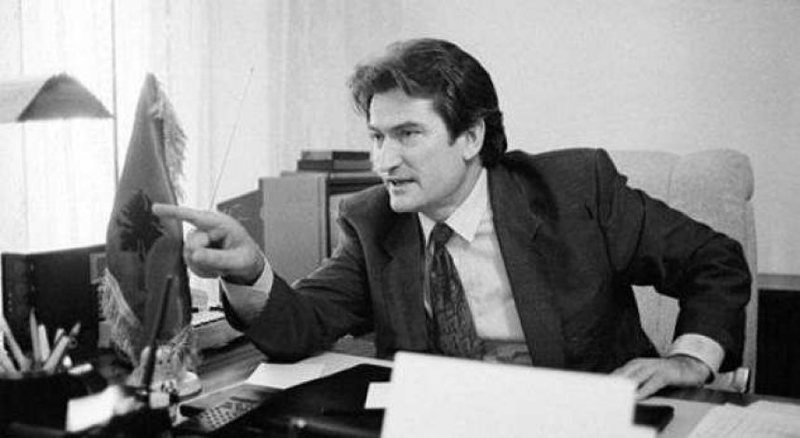

Eduard Zaloshnja recalls December '90: In Berisha's eyes there was an unearthly enlightenment - like a man whom God had assigned a mission

Eduard Zaloshnja was part of the group of students and intellectuals who, in December '90, founded the Democratic Party. A few years ago he gave a lengthy interview to the Panorama newspaper about the events of that time. We are reproducing it in full here

As one of the lecturers who joined the Student Movement of December 90, what can you tell us about the reasons for its beginning and the platform it had?

Zaloshnja: The Student Movement was a spontaneous movement that started with the demand for light and water and that eventually reached the demand for the creation of an opposition party. And it all happened in four days. Not being the fruit of an organized dissidence, such as the Czech dissidents, for example, one could not expect this movement to have a clear platform for the future. Let us not forget that only a very small minority of Albanians at that time had the opportunity to read what it took to create a complete vision of the Western democratic system. Following the RAI news was then for many of us the only window through which one could see how the democratic world worked. And that window was not enough to create a complete vision.

Which of the leaders of the Student Movement has left the most impression on you?

Zaloshnja: Among the leaders of the Student Movement, the two oldest have left a special impression on me: Azem Hajdari, sorry, and Shinasi Rama. The first was distinguished for bravery that God reserves only for heroes and the second was distinguished for a high intellectual level - Shinasiu was graduating from the second faculty and translating from several foreign languages at the time.

Were there any contradictions between them?

Zaloshnja: The main contradiction between them was about Berisha and some other intellectuals who did not join the student movement from the beginning. While Azemi immediately accepted the inclusion of Berisha and other intellectuals in the leadership of the party born of the Student Movement, Shinasiu thought that only those professors who joined the students before the meeting with Ramiz Alia on December 11 should be included in its leadership. It was Shinasiu's insistence that six students, not just two, be included in the party's Initiating Commission created by that movement. Eventually, Shinasiu lost the duel with Azem, and after a very fierce clash with Berisha in the Initiating Commission, he left the party. With Shinasi's departure, the Student Movement gradually merged with the party that gave birth to it.

What about you when you joined the Student Movement, before or after the students' meeting with Ramiz Alia?

Zaloshnja: On December 11, 1990, the students of the Agricultural University publicly announced a petition similar to what their colleagues at the University of Tirana had announced the day before. I kept in touch that day with two of the student leaders, who were my students. In the evening, I went to Student City, where tens of thousands of tyrants had gathered. There I met Gramoz Pashko and Elsa Ballauri, whom I had known before. Sali Berisha and Besnik Mustafaj were with them, whom I saw for the first time.

Minutes after I met with them, it was reported that Ramiz Alia had decided to allow the formation of an opposition party. At that moment, we started to hug each other like crazy, while the giant crowd gathered in the cheering square "Victory!". From that moment, practically, I became part of the Student Movement.

In the first news of ATSH about the opposition party that was born as a result of the Student Movement, the name "Student and Young Intellectuals Party" was used. Why and how did this name change?

Zaloshnja: After the group of students and professors returned from the meeting with Ramiz Alia, in the late hours of December 11, the full recording of the conversation with the President was heard by all those present in the Student City. When I finished listening to the conversation with Alia, I grabbed the flag that a student was holding and shouted "Long live the Democratic Party". At that moment, Azemi took the flag from my hand and told me that they had promised that the party would be called of young students and intellectuals.

After the clock had passed 12, so when the new day had begun, most of those who had met Alina, as well as Berisha, Pashko, Mustafaj, Ballauri, and I, entered Building 15. The first thing we discussed was that what would we call the new party that Alia had allowed to be formed. Berisha, who opened this discussion, said that the name that was promised to Alia for the new party did not represent either the mass of people gathered in the Student City or many others who would eventually join her. I, sticking to my initial idea, suggested the name Democratic Party. But Arben Imami opposed me because a party of the same name was the main party in the US. Instead of the name I suggested, the Imam proposed the name Democratic League. But Berisha opposed this name with the argument that the impression could be created in the international opinion that our party would be a branch of the Democratic League of Kosovo. Then I went back to my suggestion, but with one small change - the Democratic Party. Ballauri jokingly said: "By God, do not remind us of the Democratic Front!".

While others were laughing, Berisha remained thoughtful. After a few moments, he said seriously: "The Democratic Party seems to be a hit name. It would be good if the Democratic Front did not exist because the most appropriate name for our party would be exactly the Democratic Front. However, the name Democratic Party seems to me to convey the idea that it will be a part of all those who want a democratic system in Albania. Berisha's words sealed the discussion on the name of the party. After the name of the party, we discussed the party program, which we had promised to announce within the day in Student City.

How long did you continue the discussions in Building 15 and what happened next?

Zaloshnja: Around 2 a.m., we decided to sit down somewhere and write down what we had discussed. I suggested we go to my house as in those days I had no one at home. But Berisha opposed my suggestion because we should be as close as possible to the students. He said that, despite the eavesdroppers that might have been placed on Pashko's house, there was the most convenient place to work for the program. But since we were tired, it was decided to gather in the morning, after a few hours of rest. After that, we took the road home.

How did you feel on the way home?

Zaloshnja: Walking through Skanderbeg Square next to Sali Berisha, Arben Imami, Arben Demeti, etc., the feeling of being part of an important historical moment intoxicated me. And that intoxication continued until March 1991. elections after which the DP, from a broad democratic movement or front, turned into a traditional parliamentary party, with all its pros and cons.

What can you tell us something about Berisha that night?

Zaloshnja: From building 15, Berisha naturally took on the role of a leader who determined who should do what. For example, he told me to cooperate for the agriculture program with the professors of the Agricultural University Rexhep Uka and Besnik Gjonkecaj (Gjonkecaj avoids cooperation); Pashkos told him to prepare the economic program; etc. In his eyes, that night, a non-earthly light could be seen - he looked like a man whom God had just assigned a special mission.

The DP was initially chaired by an Initiating Commission. How was this commission selected among the thousands of people who participated in the Student Movement?

Zaloshnja: After the December 12 rally, where the party program was read, all those who had participated in the design of the program, student leaders, as well as intellectuals and workers from Tirana gathered at the Student Palace. In total, we became about 200 people. At that meeting, it was decided to establish the Democratic Party Initiative Commission, as well as its specialized departments. 6 students, 4 lecturers, 4 intellectuals, and 4 representatives of Tirana enterprises were elected to the Initiating Commission. Azemi was elected Chairman of the Initiating Commission. (A member of the Initiating Commission later told me that Berisha had told her privately that night that Azemi would be chairman only temporarily. And this was the first time she had met Berisha…)

We heard that Edi Rama participated in that meeting. How is it that he was not elected to the Initiating Commission or any of the specialized departments?

Zaloshnja: In fact, Edi Rama arrived at the meeting from its end, when the elections were over. He had been to Corfu in those days for a personal exhibition. According to what he said when he entered the hall, as soon as he heard the news about allowing pluralism in Albania, he held his breath from Corfu, in Igoumenitsa, in Kakvija, straight to the Student City. From the first contact with the newly formed leadership group of the Democratic Party, Rama challenged Berisha, sharply criticizing him for the public thanks he had addressed to Ramiz Alia, as well as for the calls "Long live President Alia" at the first rally of the Democratic Party. After a tense exchange of jokes between Berisha and Rama, it took Pashko's brutal intervention for Rama to interrupt the debate and leave the hall revolted.

A few years later, recalling that incident, Berisha would express in confidence that "the expulsion of Edi Rama had been the only good that the DP had had from Pashko." While months later, Rama would say in a circle of friends that "if he had been in Albania on the night of December 8, 1990, he would undoubtedly have been put in charge of the student revolt from the beginning, unlike Azem Hajdari, who welcomed the cooperation with Berisha on December 11, would have fired the doctor with the motivation that two nights ago he had presented himself to the students as Ramiz Alia's emissary ".

The mention by you of Berisha and Alia in the same sentence reminds us of the fact that there are rumors that say that the introduction of Sali Berisha in the DP was commanded by Ramiz Alia. Do you believe these allusions?

Zaloshnja: I have been told by many leading students of the movement that Berisha initially went to them as a negotiator for Ramiz Alia. Based on their stories, as well as being close to Berisha from the moment the PD was born, I have come to this conclusion: Berisha was likely sent by Ramiz Alia to the students to soften them, but when seeing that the student movement could not be stopped without permitting him to form an opposition party, he decided to join it and, eventually, be put in charge of the party that would be born. Which he officially did in February 1991.

The rivalry between Berisha and Pashko at the beginning of the Democratic Party is well known. Were behind them formed groupings or was it just a personal rivalry?

Zaloshnja: The group of intellectuals who came to the helm of the DP was an amalgam of people united by a desire to end the communist regime and to orient Albania towards the West. Among them, only Berisha and Pashko were the intellectuals who had publicly spoken out about regime change before December '90. So it was natural for them to position themselves from the beginning as the main leaders of the nascent party.

And not coincidentally, these two political figures were the most typical and prominent representatives of the two dominant categories of intellectuals that initially constituted the leading group of the DP: a-intellectuals who came from the districts who had militarily devoted themselves to the ALP and who were rewarded for this with good posts in the capital; b- intellectuals who were born and raised in Tirana and who came from important families in the communist state structure. The latter, unlike the former, had supported the ALP, not with any great devotion; were exposed early on to Western ideas, and were convinced in time that the totalitarian system should be replaced by a democratic system. While these intellectuals were less influenced by clan culture than those who came from the districts,

Editorial: How did Berisha manage to be put in charge of the DP?

Zaloshnja: About two months after the founding of the Democratic Party, when the former political prisoners started to get scared, intellectuals who had spent their lives in prisons and internments joined Berisha's group. The most prominent among them was the Albanian Mandela, Pjetër Arbnori. One of the factors that led to the gravity of this category of intellectuals towards Berisha was undoubtedly the fact that Pashko was the son of a former senior communist leader. Another reason was that they saw Berisha as a tougher and more determined leader to defeat the ALP. The approach of this category of intellectuals around Berisha tilted towards him the balance in the duel between Berisha's group and Pashko. And in the first party elections held in February 1991, Berisha, by just one vote, won.

Your mention of February 1991 reminds us of an important event that happened that month. We are talking about the student hunger strike, which was crowned with the fall of the bust of Enver Hoxha. What can you tell us about that strike?

Zaloshnja: The strike of February 1991 had its origins in the Agricultural University. One cold morning that February, when I got there, I saw that the students had gone on strike to protest the poor conditions in the dormitories. After consulting with the strike leaders, I called on the students to demand the resignation of Adil Çarçani, arguing that his government was incapable of taking care not only of the students' concerns but also of the entire Albanian people. Meanwhile, I got on the phone to the PD headquarters. Arben Imami answered the call. After I told him what was happening, he told me that he would come immediately with Azem and other students from the University of Tirana. When they arrived, the student crowd caught fire. And after the speeches given by Azemi and the Imam,

That night, when we discussed our initiative at the PD headquarters, Pashko came out with the reasoning that the overthrow of the government would bring us out as a lost party. Instead of the Çarçani government, Pashko reasoned, a more moderate government would be put in place, which could be more successful in lying to hesitant voters. While Berisha reasoned that the overthrow of the government would have symbolic values that exceeded the minuses mentioned by Pashko. After lengthy debates, it was decided to support the student strike, but not openly, as we had signed an agreement with the government to suspend strikes and protests until the election.

The students' strike, which initially consisted only of absenteeism and satirical activities denouncing the communist nomenclature (those activities were the forerunners of today's satirical MJAFT protests), was eventually supplemented by the demand to remove Enver Hoxha from the University. of Tirana. As in her last days, she became much more serious - turned into a hunger strike.

What do you remember from the day the bust of the dictator fell; are we talking about February 20, 1991?

Dr. Zaloshnja: That day I had planned to go to Rrëshen to inaugurate the establishment of the Democratic Party in Mirdita. Around 2 p.m., I set off for the streets and, if I had not heard the cheers all around, I would probably have missed the opportunity to experience one of the greatest joys I have ever felt in my life. As soon as I heard the cheers, I told the driver to take me to Skanderbeg Square and then to call the founders of the Democratic Party in Rrëshen to cancel the rally there. When I got to the square, Enver's bust was being dragged, while thousands of excited people were following him. I followed him as far as Student City, while I was constantly reminded of the sight of my father on his deathbed; shortly before he lost consciousness in the hospital, he had held out his hand to the portrait of Enver,

After arriving in Student City, I met Blendi Gonxhen, who had been the public face of the hunger strike. I suggested to Blend that he take the Presidency over the phone and ask Ramiz Alia to announce the decision to remove the university's name and overthrow the government within eight o'clock because otherwise the crowd gathered in Student City would head to the government buildings. He liked my suggestion and we both went to a nearby family, who told us he had a phone. To Blend's threat, Alia's secretary responded with contempt. But eventually, that evening, Enver's name was removed from the university and the government resigned.

Late in the evening of February 20, I remember that Azemi, Arben Imami, and I gathered at the latter's house to celebrate with a few glasses of brandy the final result of what the three of us had inadvertently started on a cold day of the beginning of February. I have never tasted more brandy in my life.

You have been at the center of the vortex of two important dates in the history of the new Albanian democracy. How do you perceive them in retrospect?

Zaloshnja: The way I experienced December 11, 1990, and February 20, 1991, has created this perception in my mind: on the first date, a public indictment was filed against the dictatorship, while on the second, was given the death sentence. The fall of the bust of Enver Hoxha in Tirana, but also in other cities, undoubtedly marks the day when the communist dictatorship was finally sent to the grave of hundreds of thousands of Albanians. Other dates, such as the date of the founding of the PD, the overthrow of the Nano government in May 1991, the plebiscite victory on March 22, 1992, etc. may have had practical values, but not the symbolic values that December 11 and February 20 had.

In closing, can you tell us why you left the PD?

Zaloshnja: When I proposed to the First Assembly of the Democratic Party that she, instead of a single chairman, have a collegial chair with a rotation of 6 months, Berisha, who was sitting next to me, stood up and said that the Assembly had just voted on the statute article dealing with the mayor. I responded with the fact that the chair of the session (Arben Demeti) had not created the opportunity to propose amendments. Upon my insistence, I was allowed to formally propose the amendment to the article. And when I argued that Albania had suffered a lot from the "legendary leaders", the hall reacted with indignation towards me. At that moment, I felt like a stranger to the party I had suggested the name to and for which I had years dreamed of being created. From that day on, I was no longer a member of any party.

Latest news

Nga Holanda në Finlandë, si operonte rrjeti shqiptar i drogës

2025-06-03 17:10:34

Tusk kërkon votëbesim në parlamentin polak më 11 qershor

2025-06-03 16:59:01

EUROPOL: Minors increasingly targeted by terrorist propaganda

2025-06-03 15:04:56

Kindergarten in Gramsh reopens where children were poisoned with salmonella

2025-06-03 14:59:16

OECD: Global economy heading for weakest growth since Covid-19

2025-06-03 14:35:26

A farm in Postribë, Shkodra, is quarantined, small livestock infected,

2025-06-03 14:21:50

74-year-old from Kamza, the oldest high school graduate in the English exam

2025-06-03 13:59:30

The average salary in Kosovo reached 639 euros in 2024

2025-06-03 13:49:00

Osmani invites parties to consult on the date of local elections

2025-06-03 13:41:33

Name/ She deceived clients and took their money, the lawyer is wanted

2025-06-03 13:25:24

He hit and killed a 59-year-old man and fled, the young man is wanted

2025-06-03 12:58:29

Two cars collide in Bulqiza, drivers injured

2025-06-03 12:34:46

15 people arrested for cyber fraud and misuse of bank cards in Gjilan

2025-06-03 12:02:41

Greece and Turkey hit by earthquake

2025-06-03 11:49:08

Due to lack of lawyers/ The hearing for the 'Golden Bullet' is postponed again

2025-06-03 11:36:52

More than half of foreigners in Serbia are Russians

2025-06-03 11:15:59

Scandal repeats, English exam thesis leaked

2025-06-03 10:46:54

They printed fake logos of well-known brands, 4 arrested, two others wanted

2025-06-03 09:42:58

A verbal agreement by Rama prompted the contested interventions in Spaç

2025-06-03 09:23:32

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-03 08:34:30

Temperatures up to 31 degrees Celsius, weather forecast for this Tuesday

2025-06-03 08:09:06

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-03 07:51:10

Convinced DP candidate: Tirana district is opening, MPs' order changes

2025-06-02 21:42:53

Cara: At the head of the state is a party that was not voted for by Albanians

2025-06-02 21:16:53

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 25th time

2025-06-02 21:10:46

"130 thousand unused ballots", CEC responds to the DP

2025-06-02 20:51:02

Italian professor who insulted Giorgia Meloni's daughter attempts suicide

2025-06-02 20:25:21

Fire breaks out in a building in Astir

2025-06-02 20:22:46

Two women threaten the Saranda prosecutor in her office

2025-06-02 19:09:20

Etna wakes up again, the most active volcano in Europe erupts

2025-06-02 19:00:36

Fire reactivates in Darëzeza forest, firefighting efforts impossible

2025-06-02 17:28:29

Cultivating cannabis on a plot, 35-year-old arrested in Mirdita

2025-06-02 16:59:27

Switzerland/ Albanian caught with drugs worth over 1 million euros

2025-06-02 16:50:38

Kosovo-Serbia dialogue meetings resume in Brussels

2025-06-02 16:32:44

The VPN Era in Albania: How the TikTok Ban is "Failing", Video Views Increase

2025-06-02 16:26:36

Mahmut Orhan brings a unique experience with Curious X

2025-06-02 16:19:55

Businesses "forgot" to pay for elections, liabilities reached 4.7 billion lek

2025-06-02 15:50:27

Photo/ Caught with cocaine, Albanian arrested in Britain

2025-06-02 15:31:12

He violently opposed police officers, 39-year-old arrested in Vlora

2025-06-02 15:04:28

DP demands Rusmal's expulsion from KAS, Logu: It is biased, Begaj's advisor

2025-06-02 14:37:24

Anemia is increasing in the population

2025-06-02 14:32:18

Fires in Darëzezë reactivate, wind spreads flames

2025-06-02 13:57:33

Traffic jams and over 14 thousand fines, Traffic Police take stock of the week

2025-06-02 13:40:51

Eurosceptic Nawrocki wins presidential election in Poland

2025-06-02 13:33:27

Hysaj: Against Serbia with calm and courage, this match is for national pride

2025-06-02 13:14:41

Bulgaria defies chaos and continues on path to euro

2025-06-02 12:53:28

Elected MP, Tedi Blushi resigns from Tirana Municipal Council

2025-06-02 12:29:36