Flash News

Flash News

The recount of votes for the Tirana district begins today

Albania among the 11 oldest countries in Europe, we aged 4 times more than the EU

Albania faces the risk of war, expert Softa in Politiko: Iran-Israel, an escalation that could also affect security in the Balkans

Horror scenes in the Tirana Morgue, decomposed bodies with worms! 18 bodies 'folded' into two 4-seat refrigerators

Korça/ A woman comes into contact with electricity

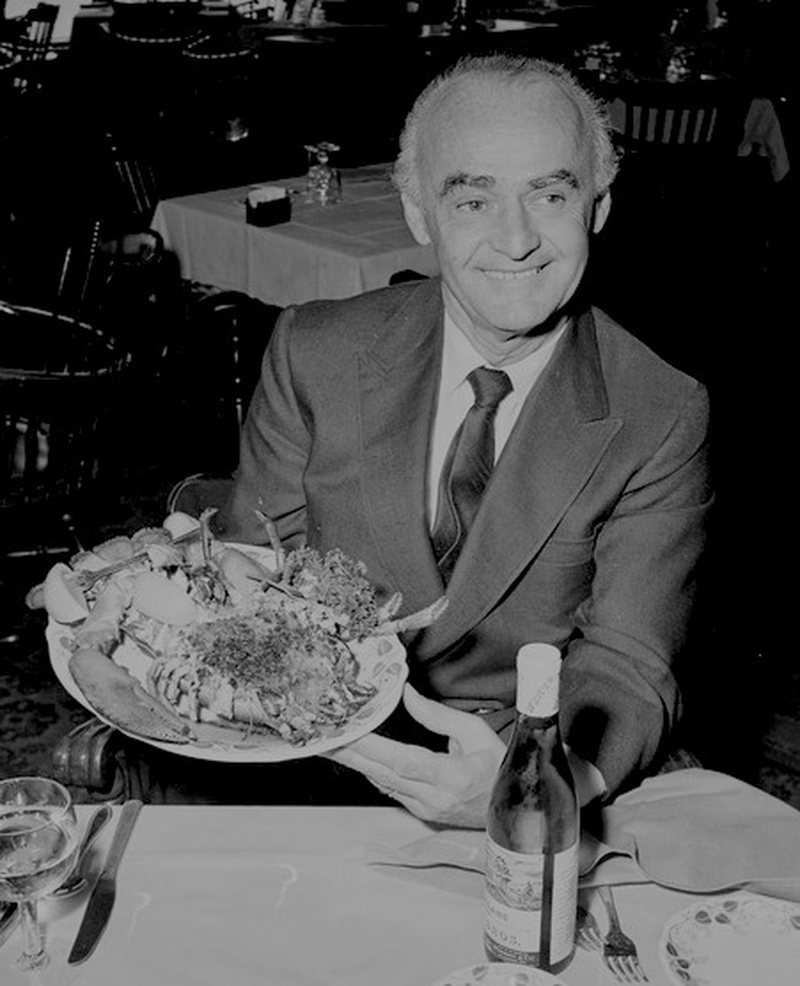

Rare interview of Anthony Athanas: We caught yogurt on the ship that brought us to America. I started by selling fruit, I lost $ 200 million in litigation

Çfarë më tha nëna kur i tregova çmimin e pianos që i dhurova Fan Nolit

THE FREETOWN VEGETABLE PEDDLER OF LONG AGO

One hundred years ago there was a young lad who had come to New Bedford from Albania. Within a few years, still a child, he was peddling vegetables in that city and Freetown. The vegetables were purchased by his father from Weiner's, grandfather and great-grandfather to present Sid Weiner's. His parents had so many children they gave some away to aunts and uncles who didn't have any.

He quickly learned how to sell: "I said, 'Lady, here's the strawberries. Take them in the kitchen. Dump them over. And if they're not all sound, you don't have to pay me.' You know, and they took them in, and I sold them all. I sold all the strawberries."

His name was Anthony Athanas. He went on to build one of the most successful restaurants the world has known. That ethic he learned at age 8 he commented in an interview: "I keep that in mind in my business today. I make sure that everything gets on that plate is sound."

Here is his interview:

ANTHONY ATHANAS

BIRTH DATE: JULY 28, 1911

INTERVIEW DATE: DECEMBER 3, 1994

RUNNING TIME: 1:00:58

INTERVIEWER: JANET LEVINE

RECORDING ENGINEER: SAME INTERVIEW

LOCATION: BOSTON, MA

TRANSCRIPT PREPARED BY: NANCY VEGA, 3/1996

TRANSCRIPT NOT REVIEWED

ALBANIA, 1915

AGE 4

PASSAGE ON "THE LETHERIA"

LEVINE: This is Janet Levine for the National Park Service. Today is December 3, 1994. I'm here at Anthony's Pier 4 Restaurant in Boston, Massachusetts, and I'm going to be talking with Anthony Athanas, who came from Albania in 1915 when he was four years of age. I want to say I'm very happy to be here.

ATHANAS: Nice to have you here.

LEVINE: Thank you. And, uh, let's start at the beginning. If you would say your birth date, and here in Albania you were born.

ATHANAS: I was, my name is Anthony Simian Athanas. And I was born in Corcha, Albania, where most of them came from. But I really, my mother was a child, and I was a child when she left the village of Trebicka.

LEVINE: Can you spell that?

ATHANAS: T-R-E-B-I-S-K-A. Trebiska. And, uh, that's where they lived many, many generations. But the Balkan War, they had to move, because the Balkan War was going. The Balkan War was involved against Turkey, which Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro and Bulgaria was fighting the Ottoman Empire. And we had to move the village, from the village, because they were burning some of the villages. And we moved to the, it must have been around twenty-five thousand then, it's about sixty now, sixty thousand, Corcha. But it's an amazing thing. All those villages, which they called the Vakafad [ph] de Corcha. The Vakafad [ph]. I think it had to do something with the religion, monasteries. I'm not too sure. They, if, but they all, if you would ask anyone, I imagine you were in Worcester, and they all told you they came from Corcha.

LEVINE: Yes, they did.

ATHANAS: Well, fifty percent of them, I dare say, came from the villages, but they were, you know, like, for example, I don't know where you live, but we here in Boston, we're in Lane, when we're out in (?), when we say where we're from we say we're from Boston, you know, it's the Boston area, or the zone of Corcha. Because if all of them today say that they're all from Corcha, Corcha should have been two million people. (he laughs)

LEVINE: I see.

ATHANAS: But they all brag they're from Corcha. I always use the words Trebicka.

LEVINE: I see. So you're thinking that they were in the surrounds of Corcha rather than having come, as you did, from Trebicka. In other words, they didn't move to Corcha.

ATHANAS: Oh, they moved to Corcha, because they found it difficult living in those areas because, excuse me, of the Balkan War was involved in that. And living conditions changed. Our people were masons, and they left, they left the village of Trebiska and traveled a couple of days with their material to build homes for the, they call them Beded [ph], for the, for the wealthy people in those.

LEVINE: So when you say our people, your family, or your . . .

ATHANAS: The village.

LEVINE: The village.

ATHANAS: There were several villages around, uh, they were, their trade is, uh, masons.

LEVINE: I see. So, so you consider your people the village, more or less.

ATHANAS: Well, I meant my people, yeah. I mean, all the people of Albania I would call our people.

LEVINE: I see.

ATHANAS: But I'm just saying our intimate areas that we're talking about, because your question was where we come from and where we resided. (he laughs) Does that make it clear to you?

LEVINE: Yes, it does. I'm curious, like, um...

ATHANAS: Okay, thank you. (addressing waiter)

LEVINE: The village that you lived in, uh, roughly how many people were there in it?

ATHANAS: Well, in that village, I have a painting upstairs of the village, uh, I have a, in that village there were two neighborhoods in that village, and I think they were, one was seven, sixty homes, the other one was thirty homes. But it's an amazing thing that it, uh, today by jeep from Corcha to Trebicka would be four hours, because they have to, you have to challenge the mountains. These villages were called Treska [ph], Trebiska, Catundrista [ph], Taberder [ph], Loarasi [ph]. They were all the villages, and that's one, Padatidi [ph]. They were all one villages. And they were really the first to come, because the first person that came to the United States was a priest from, uh, from, uh, from the town of Catundi, which is my wife's town, that came here, and that was in 18, I think it was in 1880, 1880. They were all, they all, they were the first ones. There was one before, but they don't have any records of it, but the record shows that there is some conversations with people that they came here, one came in before, but left and went to Argentina. And Argentina had an Albanian-American... Albanian- American, Albanian-Spanish newspaper, and we started immediately here an Albanian paper. Later on it became Albanian and English, see, but originally, many decades it was just Albanian. And I was president of that at one time. I was president also of the diocese, Albanian Orthodox Diocese. You know, Albanian are seventy percent Muslim, twenty percent Orthodox and ten percent Catholics. They're three religions. The Muslims were converted, you read about the Bosnia now, Bosniaks. They were part of the Ottoman Empire that converted people when they went there. They were converted as recently, some were converted as recently as the eighteenth century, but the real deep one was in the sixteenth century, the sixteenth century. Those are the three religions they have. Now, their names are different. Their names, for instance, the, uh, Muslim Albanians, they have Islam names. But the Catholic Albanians turned a little more to the western church, the Roman Catholic church. You want me to go on?

LEVINE: Uh-huh. Yeah.

ATHANAS: The Roman, uh, the Roman Catholics, they're only ten percent, (he is moved) I choke up a little bit, but, uh, they did a very good job in maintaining the language and literature, although the Orthodox did and the Moslems did, too. But they, but the Catholics had the support of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, which was, and the areas at that time, like Slovenia and, uh, Croatia. They're Catholic, see, and they're close to the Austrian and Hungarian Empire. And this, the Catholics were close, and they helped, because they were better trained and taught, because Catholic priests were educated than ours were. So, uh, they kept this country together. I mean, I don't mean to say the Catholics alone came again, but they're, they are three religions, because you probably didn't know they had three religions. I don't know. Those three religions, the leadership of those three religions kept that country together, their leadership.

LEVINE: Now, where do you fall as far as religion?

ATHANAS: I'm Orthodox like those people that you (he laughs) had in Worcester. I'm Orthodox. But it, it, uh, I am, I've been brought up to realize the trials and tribulations of the, uh, people making a country, an independent country there with, uh, with the, uh, the Serbs in the north and the Hellenic in the south. They've done a hell of a job. And they did it because they put our people, at that time we Albanians came from these villages first. And then later, not sophisticated people, not some were educated, educated, modestly educated. And these village people just came up with their cash, and they're working for five or six dollars a week and they, uh, and they would mortgage their month's pay to give to that. For instance, in 1908, 1908 or '09, they raised a hundred and seventy- five thousand dollars. And those dollars, and they did it, and this was the, uh, the renaissance of the Albanian movement was here in Boston. I gave a talk the other day upstairs and it was to the Ambassador of the United States to Albania, and he had never been to Boston. and I told him, and I'm sitting in back, I'm upstairs in the back, and I said, "Well, since you haven't been to Boston, I won't tell you that's your Bunker Hill." I said, "There, and that's the North Church," I says, "where the minister went to the Belfry and gave it two if by land and one if by sea," I said. And I says, "And now I want to tell you where you're helping, and congratulate what help you've given Albania." In these very same streets, two of the leaders of the Albanian renaissance, two of them, Fieconitsa, and Bishop F.S. Noli, who later became prime minister, I says, "They walk these streets like John Hancock, and Thanuel and Paul Revere, they walked these same streets." But a couple of hundred years after, ah, not a couple of hundred, yeah, maybe. So that's where they get their breath. And just as your shot at Concord was heard around the world, theirs was heard around the world for the Albanians right here, under this democracy.

LEVINE: Well, you're well-situated then. You're well-situated here in Boston as far as your own Albanian heritage.

ATHANAS: Well, no. I mean, we are, but we are assimilated a lot now, you know. We are, we are assimilated. And we are, for instance, I've been here seventy-nine years, but I'm not, I mean, no, of course, I'm American. They asked me the other day, he says, they made a movie of, a play of me on television, of my life. It runs for about an hour-and-a-half. And one of the questions is, "Well, how do you feel? You're such a strong Albanian. How do you feel about the difference between the land that you, you're here, and..." "Well," I says, I said, "this is the land that gave me all the opportunities. This is my adopted land. There is no difference. I love both of them." I says, "I love both lands." And I says, "But I wouldn't be a traitor to either one of them," I said, "but especially to this one because I cannot live seventy-nine years in a land and not have some allegiance, some allegiance. You owe everything to it." (he laughs)

LEVINE: Well, let's start at the beginning. If you'd say your birth date. Can you say your birth date?

ATHANAS: July 28, 1911.

LEVINE: Uh-huh. And, uh, your mother's name?

ATHANAS: Evangeline, her maiden name Peters Athanas.

LEVINE: Uh-huh. And your father's name?

ATHANAS: Simian.

LEVINE: And you had two brothers?

ATHANAS: I have two brothers. One has passed away, one here, one is with us, he's retired.

LEVINE: And what were their names? What...

ATHANAS: Arthur, my brother Arthur, and Lewis. But their Albanian names was, his name was Lazarus, and Arthur's name was Othanis. So, yeah. But they used, whenever you see an Albanian or an Orthodox with the name of Arthur, their name is Othanis. If you see anyone with Ernest, his name is Ernestos. And if you see, if you hear of one, uh, William, Bill, his name is Vasil. (he laughs)

LEVINE: So, in other words, your last name would translate to Arthur if it was an English name? A

THANAS: An adopted name, or one that's taken out of the air of no roots of any kind, no, nothing. That means it doesn't mean anything, because we don't have any Arthur. So we celebrate, the Orthodox celebrate name days. There's no evidence.

LEVINE: What is your name day?

ATHANAS: My name day is on the 17th of January, St. Anthony. My grandfather's first name was Othanis, and his is on the 18th. His was on the 18th.

LEVINE: Oh.

ATHANAS: But I'm not too knowledgeable, although I was head of the Albanian Orthodox Church in the United States, but I, I'm not, I should be more knowledgeable about it, but I...

LEVINE: Did you, do you remember celebrating a name day before you left Albania?

ATHANAS: We, uh, no, I don't.

LEVINE: How about here?

ATHANAS: Oh, yeah. Many. It was, uh, you see, when they came here, they used to celebrate name days religiously. I mean, always. And they'd lift a toast, you know, back to Albania. But they never went back. (he laughs) I think the Jews did the same, too.

LEVINE: So...

ATHANAS: I mean, most, you know, they, but very few went back.

LEVINE: But the original plan was to come here and then go back?

ATHANAS: No.

LEVINE: No?

ATHANAS: Yes. That was the feeling of them because, you know, uh, they were well, they were well-accepted, though, the foreigners, you know. And there were a lot of things about, you know, silly things, the prejudice. They had prejudice in everything. But, but he land was, my experience was tremendous, you know. I was sick from the, in the hospital for a year, and my parents didn't pay anything. And we didn't have any, it was volunteers, old families.

LEVINE: Why do you think the Albanian people are, I find them more interested in, what, contact with each other and preserving the Albanian heritage. Why do you think that's so true for Albanians?

ATHANAS: Well, I think it is for anyone, for any of them that came here, all the people that came here. For instance, I always tell this. Golda Meir was a schoolteacher in Milwaukee, and she became Prime Minister of Israel. Finoli [ph] lived here and got his degree at Harvard and his PhD at Boston University, and he, he's a prime minister. Masarak of Czechoslovakia, he put Czechoslovakia together, you know. He lived, he was married to the Lane, Crane family, the (?) Cranes. And he lived in Chicago. Ghana Boldi [ph] of Italy lived in Manhattan. Divalero of Ireland... (break in tape) (addressing someone off mic) You need the lights on over there? (voice off mic) So why don't you put them on now, see what happens. (voice off mic) The plug there, that you had. (break in tape)

LEVINE: Okay. We're resuming now and, uh, you mentioned your two brothers.

ATHANAS: Yeah, my brothers.

LEVINE: And who was the oldest, and which one was the youngest?

ATHANAS: I'm the oldest. I was the oldest. I lost my father when I was about twenty. He was fifty-one years old, fifty, fifty-one, and I was the head of the family.

LEVINE: And, uh, so, um, you mentioned before, how do you remember the four years, four to five years that you were in Albania now?

ATHANAS: I remember like in a dream, see, I was dreamed of climbing a hill, and I placed that hill, climbing, and I had trouble climbing, and I placed that hill in Trebicka because I heard mostly in Trebicka. But when I visited Albania in '89, it was in Albania. Not Albania, Corcha. That hill was in Corcha. And I remember it had a courtyard. I remember the courtyard. And I placed it in Trebicka. And that was in the, it as in the, uh, because I never went to Trebicka, but I placed it in my dreams, you know, because I heard so much of it. And the courtyard, I remember the courtyard and the tree. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Wow. And did you continue to dream that after you actually saw it there?

ATHANAS: No, no. (he laughs) No. But I dreamt, these are dreams that everyone has in your library of dreams, but not recent dreams, because I've been involved in so many things that took my attention. I'm not going to get into dreams now. That's another program for you. (they laugh)

LEVINE: Well, tell me about, um, your, whatever you remember from before you came here.

ATHANAS: I remember, I remember coming, it took three weeks, because we were, uh, avoiding the German ship because the, uh, Archduke was killed in Sarajevo. And the, uh, the first World War was getting, not hot, but they were preparing. So it took us three weeks to get here, and we were way down in the bottom. But there's one thing that we had brought. You know, yogurt, you have to have a culture to develop yogurt. Every family brought a culture. We have about thirty-two people all together, all the same clan. And we brought the culture of the yogurt. So we did make some yogurt, because we found some milk, and they put the culture into it, and then set it, covered it up with blankets, as I remember seeing them do, you know, and my mother used to do it later on, too, and get the yogurt. And we had bread and onions and things like that. So we had the, and we all brought, oh, an amazing thing, when I look back in the history of our people, that they all brought the culture of the yogurt. Because they couldn't find it here, because was no yogurt here. Now it's very famous. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Yeah, oh, yes. When you say your clan, did you actually know all the thirty-two people?

ATHANAS: Oh, yes, yes. I brought up with them. We were brought up here. We lived in New Bedford. All, one lived in, one family lived in New Bedford, what do you call those mountaineers in Kentucky? What do you, refer to the, I forgot, you know, I thought you could help me with that name. One clan lived in one, one family.

LEVINE: Like Appalachia?

ATHANAS: Well, you know how the people lived in the mountains of Kentucky.

LEVINE: Uh-huh.

ATHANAS: You know, and they had feuds. And that's Albania, too, had, you know, feuds, the same things as there. (he laughs) So we, we had our feuds, too, with this (?). But we lived in New Bedford.

LEVINE: And that's where you went when you first arrived?

ATHANAS: In New Bedford. My father came here much before, and he went to Fitchburg, but we came here to New Bedford. So we all lived here. And...

LEVINE: What was the name of the ship? Do you remember it?

ATHANAS: Yeah. Letheria. In Greek that means freedom. It's an interesting thing. See, we left from Greece, Piraeus. And the ship's name was Letheria. It was the Greeks. We're not far from the Greek border, you know. Uh...

LEVINE: So, um, you mentioned that the people first went from, uh, from, uh, the village, before you, when you were in utero, but when your mother went.

ATHANAS: No. Uh, there were many generations in the villages, many. I believe those villages were in the area of Stephen Duchan in the 12th Century. Because, and the names are Slavic, those names. See, the Slavs came in the sixth century, into Yugoslavia, you know. But, uh, they, uh, what's the question now?

LEVINE: Well, I was asking, would you consider that when your family came here they were refugees? Would you call that, or would you...

ATHANAS: They were immigrants.

LEVINE: They were immigrants.

ATHANAS: Yeah.

LEVINE: But when they went to...

ATHANAS: There was no, uh, nobody forced them to get out. It's just that the conditions, like all people came here. Let me give you one of the best examples why people came here. Bismarck was the first one to have Social Security. Did you know that? Bismarck was the very first one, in the middle of the nineteenth century, Bismarck. You know the largest ethnic group here in the United States? Germans.

LEVINE: Yes, I have heard that.

ATHANAS: Germans (?). They left, you know when we got Social Security here? In the '30s, okay? Those people left, because I want to get back to what the crux of this thing is. They left Germany having Social Security there, but came over here because the opportunities were here. You ask me why did they come here? They came for better opportunities and better living for their families. (he laughs) Because America, America is, everybody dreams of going to America, you know. (he laughs)

LEVINE: It wasn't persecution. It was opportunity.

ATHANAS: No. It wasn't persecution. Well, let me say persecution. Let me put it this way. There were feuds among the groups, you know, but, no, it wasn't, uh, that we were persecuted like, uh, like, uh, the Armenians, like the Jews were persecuted. We could not go from village to village without being robbed. No question. Robbed all the time. They were robbed, apparently. My grandmother had a good reputation in the village. She had a hole there, and she had a gun right in the hole. (he laughs) We were, robbery was, not only in Albania, but there were bandits in all those, southern Italy, you know, there were bandits, uh...

LEVINE: Were the bandits of a particular...

ATHANAS: You gone off here? (referring to the tape)

LEVINE: No, we're good.

ATHANAS: The bandits were, yeah, sure. But in the city, though, they were. But going from the village to the city, some terrible experiences.

LEVINE: Huh. So that was a fact of life.

ATHANAS: Yeah, that was it. But no different than other, other areas, and no national education. Education was done by the church, and the church was Greek, and the people didn't know Greek, but they soon knew it, because that's the only thing that was allowed to teach. And Albanian was out of the question.

LEVINE: So the children learned Greek once they went to school.

ATHANAS: When they went to school, that was my father's time. They learned Greek. But they didn't know how to speak Greek. They spoke Greek. Wait a minute. They spoke Greek, they learned to speak Greek, but with an Albanian accent. And, uh, my father, I sold fruit and vegetables with my father, and he would do, you know, eight times eight, sixty-four. And he'd do it in Greek. I said, "But, Pa, why do you do it that way? Why don't you do it in Albanian?" "I can't do it in Albanian," he says. "I wasn't taught. I never went to school in Albanian." "How did you learn," I said to my father. "How did you learn Albanian then?" I says. "The same as you're learning it now," he said. Because he used to be teaching me. "Read the newspaper," he says. "Read the newspaper. It's easy. It's a phonetic language." You see what I mean? He said, "The same as you're learning it now. I learned it like you're learning it now. You read Albanian pretty good, don't you?" He said, "Fair." I says, "Well, you read it very good." "Well, I've been working at it longer, but that's how we learned it," he says.

LEVINE: You wouldn't remember your father from Albania.

ATHANAS: No.

LEVINE: But do you remember anything he told about when he came here before the rest of the family?

ATHANAS: Well, he came here and, uh, he, they had the same jokes they played on foreigners, you know. One of them was, he works in Johnson, Harvey Johnson, and made arms in Fitchburg. (he laughs) They were, had electricity, and they went to him and told him, "See this wire here? Take this wire and shove it up that open line, right like that." And he knocked him to pieces, you know. ( he laughs ) They had things like that, you know, and ginny, you know. And you know what they have, what they used to refer to the local people here? "Boy, these foreigners are something!" And they were the foreigners. ( they laugh ) They would refer, I remember them saying, I says, I would say to them, "Foreigner? You know who the foreigner is?" "Yeah, I'm talking about that foreigner there." "You're the foreigner here. It's his land. He came here before you." (they laugh) (break in tape)

END OF SIDE ONE BEGINNING OF SIDE TWO

LEVINE: So, um, how about your grandmother? Do you remember her?

ATHANAS: Oh, I came over with her. I have pictures with all that. Yeah, I came over with my grandmother. My grandfather, I remember my grandfather. I remember in Albania, my funeral of my grandfather.

LEVINE: Oh, could you talk about that?

ATHANAS: Yeah. I don't know much, I don't know much about it, but he was laid out. You know, a body laid out. No coffin or anything.

LEVINE: In the house?

ATHANAS: A table in the house. In the house, and, and it's an amazing thing why I remember it. As a rope around his ankles, there was a rope tied up on it. I don't know why. Even to this day, I don't even know why they had that. But I asked. I remember as a little boy asking, "What's the rope doing? What has Grandpa got a rope there for?" (he laughs) It's a silly thing to talk about, but...

LEVINE: No, that is interesting.

ATHANAS: But I have never found out, there must have been some custom, you know. Uh-huh.

LEVINE: Yes. Well, if I ever find out, I'll tell you. (they laugh) So, and your grandmother. Do you remember experiences with her in Albania?

ATHANAS: Oh, sure. She used to tell us all the stories. She told stories. And stories that were appropo, relevant to whatever we were discussing, or whatever we were experiencing.

LEVINE: Oh, my goodness. Can you remember any?

ATHANAS: Oh, terrific stories, terrific. I remember them all, honestly.

LEVINE: Oh.

ATHANAS: There's one about a tingere [ph]. A tingere [ph] is a cooking pan, and the nastradin hoja [ph] is all based on this character, nastradin hoja [ph]. Hoja means Muslim priest. And he went to his neighbor. Have you got time for this? You want me to . . .

LEVINE: Yes, absolutely. This is wonderful.

ATHANAS: And he says, and he said, the neighbor, he says, "I want to borrow a tingere [ph]." He says, "What do you mean you want to borrow, how long are you going to keep it?" He says, "Just a couple of days. I'll bring it to you." "You sure you're gonna bring it," he says, "in two days? I don't want this, you know, you're not dependable sometimes," he says, you know. He says, "Two days I'll bring it to you. I have a big party, and I don't have a tingere [ph] to cook the meal." He gave him the tingere [ph]. He gave them the tingere [ph], he put it, but he put another tingere [ph], a small tingere [ph] in the big tingere [ph] like this, see. And he gave it to him, and he brought it back to him the second day as he promised. He says, "Yeah, thank you, but what is this here for?" He says, "Oh, I got good news for you. The tingere [ph] you gave me had a baby," he says, "I birthed this." The next time he came over, I'm gonna make it short. The next time he came over he went and says, "I want to borrow a tingere [ph]." He says, "Anyone you want." He never asked any questions or anything, he took the tingere [ph], he kept it three or four weeks, a month, and he went, sheepishly and asked, "Nastradin hoja [ph], what happened to the tingere [ph]?" He says, "What's the matter? You haven't brought it back." He says, "Well, I got bad news for you," he says. "What's happened to the tingere [ph]?" He says, "It died." He says, "How can the tingere [ph] die?" He says, "If it can have a baby, it can die." It's a con artist's game. That's the, that used to teach us not to be gullible, not to be gullible. When you get something, be careful.

LEVINE: Oh, my goodness. And your grandmother made up the story?

ATHANAS: Well, my father mostly, and my grandma. No, they weren't made up stories. They were stories told from generation to generation. My father used to tell me, he says, "Nastradin hoja [ph], his cattle, his sheep destroyed the vineyards. Take him to court." He takes him to court. He attorney said, "Now, you listen to me. The same clothes you wear now as a shepherd, you put those on. Don't put anything else." He says, "I don't have anything else." "Put those on," he says. "You go to court, and all you've got to do is remember one thing." He says, "Any question they ask you, you're sad, you have no education, just go this way." (he demonstrates) So all through the case he went this way, this way, and when it was all over the judge, the attorney, you know, he said, he said to him, "Did we do it? You're the best attorney anyway," he says. "Here's my bill," he says to him, like that. He went. (Dr. Levine laughs) So the story is, don't give too much information. Okay. I've had enough of this. You're thinking too much.

LEVINE: That's wonderful. That's wonderful. Okay. So let's, um, let's say, uh, when you came here, then, you went to New Bedford, and then did you start school?

ATHANAS: Yes, I started school. And I left at recess time, and the truant officer came after me. (he laughs) That's true. And I used to deliver the lunches to my relatives. They worked in the cotton mills. My mother worked in, was a spinner, a weaver in a cotton mill. And, uh, I, uh, I got their lunches, and I think I used to get ten cents, five cents. So here's a good one. I had a quarter from one person, and my father says, "How much you made?" He didn't expect a quarter. The first quarter I made in my life, I went to my father, and he rubbed it here. That was the custom. He'll have as much hair as I got on my beard, you know, the quarter. And I was, it was very, to me, I remember it. Of course, I have a fantastic father. Oh! Everything I, he, we paid his funeral bill, twenty-five dollars, you know, twenty-five dollars a month, you know. But he left me such a treasure of things, you know. (he laughs)

LEVINE: He rubbed the quarter on his beard, and it was to say, "You should have as many quarters, or money..."

ATHANAS: Yeah, that's right.

LEVINE: As I have, uh-huh.

ATHANAS: Yeah, you know, wish you as much health as I have, you know. Not exactly. But I, my father was not the only one. They all used to do that.

LEVINE: So, um, well, it sounds like your father had a really strong influence.

ATHANAS: Very much.

LEVINE: Yeah, yeah.

ATHANAS: He wasn't aggressive like I was. He wasn't, you know, always said, "Don't be too greedy. Don't get too greedy."

LEVINE: Huh. Uh-huh. (Mr. Athanas laughs) And, so was he in New Bedford when you first came here?

ATHANAS: Mmm. He died in 1932.

LEVINE: Uh-huh. Do you remember the ship coming into the New York harbor when you were arriving here?

ATHANAS: Like in a dream.

LEVINE: And, uh, anything about Ellis Island? Is that anything that you can remember from that early age?

ATHANAS: I remember that I wasn't very well. They were concerned about me going, sending me back. Because there was one of them in our group had, because tubercular was quite prevalent in those days. And one of our group was sent back because he had a case of, which was...

LEVINE: Do you remember anything about that, about being sent back, about how people felt? (disturbance to the microphone)

ATHANAS: I remember how we were crying, and everybody was crying, you know. But do you remember the play Rags, about Ellis Island? You don't remember. They showed it, but it exaggerated a lot. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Oh.

ATHANAS: To what my people say. Because I can't remember too much of that.

LEVINE: Yeah, yeah. Okay. So what was your experience like going to school, when you first went to school here?

ATHANAS: Well, I couldn't speak English, you know. And I thought, as I told you before, it was recess, and I went. And I remember my first teacher and she, you know.

LEVINE: Do you remember her name?

ATHANAS: Palmer. I remember the school, Cedar Grove Street School. And then I went to this third grade, fourth grade in the Phillips School, and the teachers, and they came, and they wanted to have, it was their hundredth anniversary and they asked me to come. They had two people that they thought they had accomplished something in life, so they had me come out there, and the Albanian television was here to write the story. So I went there and I had a good time with them, you know, in the school. The principal, of course, they all, I'm very well-known, you know, everywhere. You know, everywhere. I walk in New York in the streets, and they recognize me, so, you know. Because I've been in business here so long, and we serve a half a million people a year here. So they, people in the streets know me in New Bedford, you know.

LEVINE: How does that feel, when somebody knows you in the street?

ATHANAS: Fine. Well, of course, it feels good no matter, you know, yeah. And a lot of them get very nostalgic, you know, when you get to be my age, and they are, too, you know, and they, they don't let you go very easy. (they laugh)

LEVINE: Well, do you know, do you know what drove you?

ATHANAS: The what?

LEVINE: What drove you to accomplish so much as you have?

ATHANAS: Well, I have lost a lot, too. I owned all these thirty-five acres, and in a court case, I had a, I owned it all, but I got in partners with some people and, uh, I lost two hundred million dollars. All the land that I accumulated and the money that it cost me to accumulate it. So, but we're still coming out of it. So, uh, I didn't go that, you know.

LEVINE: But the fact that you, that you had all that to lose. I mean, do you know what pushed you or drove you, or what it was that you wanted?

ATHANAS: Well, I did the same thing when I sold newspapers as a kid, you know. I've, I don't want to...

LEVINE: You can brag, it's okay. (she laughs)

ATHANAS: When I sold newspapers and, you know, peddled fruit, I emptied the truck out, you know, selling it. I didn't go home till I finished it. It always stands out. There's certain people just, you know, like that. Yeah, I guess, because my brothers weren't that way.

LEVINE: Tell me about the things you did. Like you started out with bringing the lunches to the mill, and then what?

ATHANAS: I have a, I used to bring the lunches to them. But the one of that, when I sell fruit, my father, one wonderful experience was my father sold fruit and vegetables, so I told my father, "I want those strawberries, and I'll go around and sell them." "No, you're too young," he says. He'll do it. I went in every door just, you know, how peddlers, they slam the door. And the, the strawberries went and melted, you know, the sun beating on them. I didn't have, I brought them back. He lost them. And he says, "It's not your fault." He says, "The strawberries weren't very good." He says, "And it's my fault." Another father would say, "I told you not to go."

LEVINE: Yeah.

ATHANAS: He wouldn't.

LEVINE: Huh.

ATHANAS: And, uh, so, so, and then a few days later I said, "Pa, give me those strawberries, will you?" He says, "Oh, no, no, no." He lost them, you know. So I went to them, and I said, "Lady, here's the strawberries. Take them in the kitchen. Dump them over. And if they're not all sound, you don't have to pay me." You know, and they took them in, and I sold them all. I sold all the strawberries.

LEVINE: How old were you about, around?

ATHANAS: Oh, about eight. You know what I mean, I'm eight years old. And, uh, you see, uh, I, I found out, as a boy, that I could sell, but I made sure those strawberries were damn good, you know. So I keep that in mind in my business today. I make sure that everything that gets on that plate is sound. I'm buying fruit and vegetables today from the Weiner [ph] family that I bought from his grandfather. And you know this kid, Weiner [ph]? When do you ask people how they get it and how they have it? He's got the best fruit and vegetables, better than his grandfather ten times. His grandfather used to con us sometimes, you know what I mean, but this guy has got the best of everything. And how did he get it? He's just that way. He has just the best. That's how people, some people are. They shine shoes, and they say, "I don't want a shine." "Put your foot here, sir. You don't like the shine, you don't have to pay me." (he laughs) You know what I mean? And (?), you know, you give him something, give him confidence, give him confidence that those strawberries are sound, give him confidence that you're going to do a good job.

LEVINE: Yes, I see. Did your father have a store, or did you...

ATHANAS: No, we had a, we had a store, and we lived behind the store, and we had a barn in the back to keep the horse, Billy. And, uh, and later he bought a truck. But, uh, and we had a pushcart before that. And, uh, and in the store, my mother kept the store, my father went out peddling fruit. My mother was the worker.

LEVINE: Oh, so you got your work ethic from her as well.

ATHANAS: Well, from him, too, but in a more philosophical way, see. And a more, you know, in a thinking way. You understand? You know, just, uh, you know, there's a word seckel [ph]. You never heard of that, the Yiddish word?

LEVINE: Sekel [ph]?

ATHANAS: Sekel [ph]. Well, that means you've got to have... (he laughs) It's just, this stuff doesn't come from a textbook.

LEVINE: Uh-huh. Right, right. But your, it didn't affect, your mother and father's influences didn't affect your brothers in similar ways?

ATHANAS: Oh, yes. They were too young. Oh, yes. Because for my, my youngest brother didn't have, he knew him, you know, but he was adopted by my uncle. Yeah. Um, craziest custom they had, if one of them didn't have any children, a brother didn't have any children, and one had like eight we had, you know, before. We had altogether ten, but two passed away. And they, it was ridiculous. They let them adopt him. Because he used to spend the summers with us all the time, and I would go over with him, I would be with him. I'm ten years older than he is. So when he was four I was fourteen, and I used to be with him all the time, you know. And I would be with him, my father would insist upon me being with him all the time, you know. Yeah. He's a pilot in the Schnaltz [ph], you know, in the war, quite a fellow. My brother Louis was very, very good, very smart, very good. High school only but, uh, very well- read.

LEVINE: Um, let's see. Uh, as far as your progress in your work, you did the delivering of lunch and then the...

ATHANAS: Fruit.

LEVINE: Fruit. And then how did you...

ATHANAS: In the restaurants, then. I worked in the, I started lighting stoves. Those days were burnt, restaurants was coal and wood, because the other thing was expensive. And I knew something about coke. I used to go to the mills of New Bedford, Cotton Mills, and my family, my mother never had to buy any coal or wood. I'd bring them home from the coke. You know what coke is? The unburned. I'd stack up the cellar with coal. ( he laughs ) You know, you see his house, you know, the shingles coming down, and just watch which houses were getting new shingles, and then we'd get the shingles and start the fire. But I knew how to start a fire. (he laughs) So in the restaurant my job was to get in the morning and light the fires for the chef, and I watched him, you know, doing that. But, uh, an amazing thing, though. The students, they always ask the question of whether, did I go to the oracle, and the oracle said to me, "You've got to be a restaurant man, Anthony?" Nah! I was hungry, I had to go work in a restaurant, do anything. You know how we used to look for jobs during the cotton mill strike? We'd see if any chimneys, stacks of chimneys was smoking, boy, there's a job over there, we'd better go over there. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Oh, wow.

ATHANAS: You see?

LEVINE: So do you remember any, um, political or, um, any events, world events that took place during your lifetime that you, particularly affected you? I mean, you came over during the First World War.

ATHANAS: Before the First World War.

LEVINE: '15, 1915, yeah, right. Before we were in it. But is there...

ATHANAS: Here?

LEVINE: Yeah, or maybe President Roosevelt, or any figure or...

ATHANAS: Oh, President Roosevelt...

LEVINE: Event that influenced you?

ATHANAS: Ah, huh, I just don't, I, influenced me? I don't know of any, I mean, figures, of course, they did. I mean, reading about Abraham Lincoln and all the compassion he had when they played Dixie, you know, when the war was over, you know, and things about Abraham Lincoln, you know. And even Calvin Coolidge, who they didn't think very much of. I liked the stories, you know, when he came out of the church, and the journalist said, "What did the ministers think of?" He was, you know, he was very, absolutely didn't talk much at all. Silent Cal, they called him. The minister came, and he says to him, "But the minister said..." The reporter said, "What did he speak on?" He says, "Sin." "What'd he say about it?" He says, "Against it." (they laugh) You know? So, I mean, things like that, they come up. But what inspired, look. I boxed and wrestled. I watched what the best were, and I tried it. And I'll go to the circus and see them new on trapeze. I didn't want to get on the trapeze, but I said, but I used to say to myself, "Gee, if I do anything, and anything I do, I want to do it as good as that guy." Get on the trapeze and, you know, that's what inspired me the most." Every job I saw that was done very, very well, which I was not in it, but even today I'm the same way. If I see anything that they do it so well, I think I should do it. This is where I spent my thing. I mean, I didn't think of, I don't know, I think it was, this was the way I felt. If I saw someone doing it well in anything, like I mentioned these things, I just, it inspired me to, even today I do that. I repeat it again. Even today I do that.

LEVINE: Okay. Is there anything...

ATHANAS: I talked too long.

LEVINE: No. Well, we're nearly to the end of an hour. We have a little bit more time. Do you want to take a little pause?

ATHANAS: No, I don't. No. No, I don't.

LEVINE: Is there anything else that you might say about how coming to this country from another place had an influence on you, the fact that you came as an immigrant to America? Do you think that figured into your, um, personhood in any way?

ATHANAS: Well, I wasn't at four or five years old you're not knowledgeable about the land you left. But I know with my people, the stories they tell me, what they left. And I drew from them that, that I was thankful that I was here. (he laughs) You know what I'm saying? I drew from them. But I, I didn't experience anything there. Uh, that's the only thing I can describe.

LEVINE: Okay. Well, um, is there anything else that you can think of relevant to coming to this country or Ellis Island or, before we close?

ATHANAS: Uh, well...

LEVINE: Um, maybe what you're proudest of in your life.

ATHANAS: Well, I'm proud about the land we live in. I'm proud of this land. I couldn't imagine living anywhere else. You know, sounds corny, maybe, to some people, you know, because they find, they find so many flaws in it, but nevertheless, I mean, I couldn't imagine living anywhere else. And, um...

LEVINE: When you've gone back to Albania, has, uh...

ATHANAS: I've been back three times.

LEVINE: Uh-huh.

ATHANAS: During the time of Edmir Hoja [ph] they didn't want me there, because I was a bad example, and, as a matter of fact, they said, "We will try him in court," to what extent. But his successor, Rabi Saldia [ph], they said, they said it was all right. They invited me, as a matter of fact. Because they wouldn't let many people go in there, you know, that were not, if you didn't say anything good about them.

LEVINE: I see.

ATHANAS: And I was, well, communism didn't fit well with my scheme. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Uh-huh.

ATHANAS: And, uh, Albania's a very poor country. They're very proud people, if you want. When I think of Albania, I don't know how it ever became a state with the neighbors it has. (he laughs) With, if you've got neighbors like Albania has, you don't need any enemies. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Well, you are considered a prominent Albanian-American figure.

ATHANAS: Yes, that's a burden that I don't want. (he laughs) I, um, I think it is so, yes. You've spoken to people in early areas that are Albanian that they regard...

LEVINE: They regard you as...

ATHANAS: They regard me as. And at the same time you're not a prophet in your hometown. (he laughs) You know, I am, I am regarded by them, but still, I'm not, no one's a prophet in his hometown. Remember that. You've got to prove yourself every day. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Well, do you have any, uh, sort of agenda, or do you have any philosophy or ideas that you would like to, um, carry out, as far as the Albanian-American community is concerned?

ATHANAS: Well, I'm, uh, I have been in that position economically to be helpful to them, and I'm going to continue to do that. And I'm not the Anthony Athanas that I was because of what happened, but still we're in, we're not in bad shape. (he laughs) And I'm going to continue to help them out. That doesn't mean to say I'm not going to help my responsibilities to this land and to the agencies, and being in business I help, I want to be helpful to all, not only the Albanians, because my father always. You know, the tenth, the tenth? A tenth of your wealth is carried... (he laughs)

LEVINE: Is to be, is for charity, is to be given?

ATHANAS: Huh? Yeah.

LEVINE: Yeah, uh-huh.

ATHANAS: Well, I've, I've done a little more. (he laughs)

LEVINE: Is there any...

ATHANAS: I bought a piano for the church and, uh, I went, in 1941, I paid eighteen hundred dollars for it. And at that time the former prime minister of Albania was the bishop there, Fafanoli [ph], and I had a good time. And I told my mother. I went back home and told my mother. I'll make it short. I went home, my mother, and I told my mother, and she says, "How proud your father would be." And she said, and I gave her the price of it. "Now, since you've now given the price," she says, "the good Lord has wiped it off the slate, that good deed, that you did it." She say, "You never should give a price that shows how much you've given." (they laugh)

LEVINE: That's great. Okay. Well, is there any philosophy that you would espouse as far as the American, Albanian-American people today, as far as what's needed or what's, what's, uh, good for their benefit? Is there any idea that you...

ATHANAS: Well, I've spoken so long about everything, I think you can grasp some of it from within that thing. I don't think I have any...

LEVINE: Yeah, okay. Okay. Well, I want to thank you so much. It was really so interesting. I really enjoyed everything you had to say.

ATHANAS: Well, thank you.

LEVINE: This is Janet Levine. It's December 3, 1994. I'm here with Anthony Athanas, and we've been talking about coming to this country and to Ellis Island. And, let's see, you would be, how old are you today?

ATHANAS: I'll be eighty-four next July.

LEVINE: You'll be eighty-four? So, Mr. Athanas is eighty-four at this time. Okay, signing off.

Latest news

Socially dangerous person, 27-year-old arrested in Pogradec

2025-06-18 08:51:39

The recount of votes for the Tirana district begins today

2025-06-18 08:37:37

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-18 08:12:05

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-18 07:45:20

Former prosecutor: Criminal groups are more structured in Albania

2025-06-17 22:02:21

Korça/ A woman comes into contact with electricity

2025-06-17 20:55:40

Death makes you neither good nor bad.

2025-06-17 20:38:05

Only 1 in 5 tourists sleep in apartments or hotels

2025-06-17 20:25:16

European Commission proposes complete ban on Russian gas imports

2025-06-17 19:46:58

'Serious concern': EU condemns government attacks on SPAK after Veliaj's arrest

2025-06-17 19:36:01

Fuel prices soar amid Israel-Iran tensions

2025-06-17 19:19:12

Iranian military says it struck Israeli military intelligence center in Tel Aviv

2025-06-17 18:17:27

The recount of 94 boxes of Gramsh and Peqin is completed

2025-06-17 18:08:47

Source: The world order is destroyed, how is the world being run today

2025-06-17 17:50:28

Albania and Serbia begin evacuations from Israel, Kosovo no clarification

2025-06-17 17:20:50

Exports have no power to recover, businesses suspend investments

2025-06-17 17:10:36

Atlanta United close to deal with Albania international center back

2025-06-17 16:59:03

The Bridge over the Buna hostage to bureaucracies

2025-06-17 16:50:46

'The White Horse of Celibashi'

2025-06-17 16:40:25

SP MP leaves SPAK, shuts up about the media: I can't speak

2025-06-17 16:29:15

Why was Belgium chosen for the Special Court convicts to serve their sentences?

2025-06-17 16:21:46

'Bunker-busting' bombs and Iran's nuclear base on a mountain

2025-06-17 16:18:53

Mother and daughter rape 14-year-old girl in Tirana

2025-06-17 16:08:15

Extreme temperatures, here are the foods you should eat to cope with the heat

2025-06-17 16:00:17

Cannabis was found on him, 20-year-old arrested in Vlora

2025-06-17 15:24:17

A dead body is found on "Bulevardi i Ri" in Tirana

2025-06-17 15:21:09

Fire in Elbasan, OST buildings engulfed in flames

2025-06-17 15:05:29

Egnatia learns the opponent in the Champions League

2025-06-17 14:55:26

Murder of Pjerin Xhuvani in Elbasan, Arbër Paplekaj requests conditional release

2025-06-17 14:45:24

The best cities to live in the world, Vienna falls from the throne again

2025-06-17 14:36:54

Plarent Ndreca summoned to the GJKKO

2025-06-17 14:31:16

Requests conditional release, hearing for Ervin Salianji postponed

2025-06-17 14:17:35

5 Albanians evacuated from Israel, expected to return to Albania

2025-06-17 14:06:31

Israel-Iran War/ Analysis by "The New Times": Who can endure more pain?

2025-06-17 13:10:39

Special Court leaves Veliaj in prison, SPAK presents new evidence

2025-06-17 12:57:51

The conflict between Israel and Iran floods the Albanian media with fake news

2025-06-17 12:28:49

Part of a criminal group, 54-year-old (Name) arrested in Tirana

2025-06-17 11:17:42

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 33rd time

2025-06-17 11:05:16

EU Ambassador: Criminal networks are using corruption to gain power

2025-06-17 10:37:45

Salianji requests conditional release, hearing to be held today at Fier Court

2025-06-17 10:15:40

Albanian caught with firearm in suitcase, arrested in Rinas (NAME)

2025-06-17 10:05:06

Israel says it has eliminated Iran's Armed Forces Chief of Staff

2025-06-17 09:52:30

BIRN: Recount of May 11 ballot boxes will last until July

2025-06-17 09:32:15

Seeking freedom, the Supreme Court will review Veliaj's appeal on July 8

2025-06-17 09:22:43

Accident on the Delvina-Saranda axis, "Toyota" goes off the road, driver injured

2025-06-17 09:10:08

Israel fires rocket barrage towards Israel

2025-06-17 08:31:44

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-17 08:13:40

Rain returns, here's the weather forecast for this Tuesday

2025-06-17 07:59:33

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-17 07:46:33

Media: Iran tried to shoot down Trump's plane during the election campaign

2025-06-16 22:04:15

Netanyahu: Eliminating Khamenei would end the conflict with Iran

2025-06-16 21:47:13

Lala: If the Supreme Court acquits Veliaj, a precedent will be created

2025-06-16 21:34:12

Laura Fazliu wins bronze medal at the World Judo Championships

2025-06-16 21:13:32

Car falls off bridge on Saranda-Delvina road, driver injured

2025-06-16 20:58:56

Tourist from Slovakia drowns near the Rock of Kavaja

2025-06-16 20:33:42

Cases of residential burglaries increase significantly during the summer

2025-06-16 20:19:28

Can Trump convince Netanyahu to stop attacking Iran?

2025-06-16 20:17:52

UN financial crisis puts aid for refugees at risk

2025-06-16 19:59:17

Tirana/ 253 complaints for road violations in just one week

2025-06-16 19:24:59