Flash News

Flash News

Mass poisoning in Gramsh's garden, Elbasan Prosecutor's Office launches investigations

Attempted to kill 58-year-old man with axe in Fier, father arrested, son wanted

Explosion with explosives in a bar in Berat

A car caught fire on the Fier-Lushnje road

Shuhet në moshën 86-vjeçare regjisori i njohur Piro Milkani

It was September 2023 when lawyer Rhys Palmer received his first call from an alarmed university student, accused of using an artificial intelligence chatbot to cheat on his assignments. It was the first of many. Less than a year earlier, OpenAI’s ChatGPT had launched, and students were already using it to summarize scientific articles and books. But also to write essays.

“From the first phone call, I immediately thought this was going to be a big deal. For that particular student, the university had used its own artificial intelligence to detect plagiarism. I saw the potential flaws in that process and predicted that a wave of students would face similar issues,” says Palmer, from his office at Robertsons Solicitors in Cardiff, where he specialises in education law.

As the use of chatbots becomes more widespread, what was initially a minor annoyance has become a profound challenge for universities. If large numbers of students are using chatbots to write, research, program, and think for them, what is the point of traditional education?

Since that first phone call in 2023, Palmer has carved out a niche for himself by helping students accused of using AI to cheat on coursework or online exams. He says most students have been acquitted after presenting evidence such as pre-written essays, study notes and previous work.

“'AI copying' is… a separate issue. It's often parents who are calling on behalf of their children. They often feel that their children haven't received clear guidance or training on how they can and cannot use AI,” says Palmer.

In other cases, Palmer has helped students who admit to using AI avoid punishment by arguing that the university's policies on AI were unclear, or that they had mental health issues like depression or anxiety.

“They come in saying, 'I was wrong.' In cases like that, we get a letter from the family doctor or a report from some expert confirming that their judgment was impaired,” he says.

'It was really well worded'

Some students report that ChatGPT is now the most common program to appear on students’ laptops in university libraries. For many, it’s already an essential part of everyday life. Gaspard Rouffin, 19, a third-year history and German student at the University of Oxford, uses it every day for everything from finding book suggestions to summarizing long articles to see if they’re worth reading in full. For language modules, the use of AI is arguably more controversial.

“I had a professor in my second year, in a translation class [into German], and she noticed that a lot of the translations were generated by AI, so she refused to grade the translations that week and told us never to do it again,” he says.

Other lecturers have been less vigilant. Another third-year student at Oxford recalls a tutorial where a fellow student was reading an essay that she felt was clearly generated by AI.

"I knew it right away. There was something about the syntax, the way it was constructed and the way she was reading it," she says.

The lecturer's reaction? “He said, ‘Wow, that was a really great introduction, it was really well-worded and I liked the precision of it.’ I was just sitting there, thinking, ‘how do you not understand that this is a ChatGPT product?’ I think that shows a lack of knowledge on the subject.”

A study by student accommodation company Yugo shows that 43 percent of UK students are using AI to correct academic work, 33 percent use it to help with essay structure and 31 percent to simplify information. Only 2 percent of 2,255 students said they use it to cheat on assignments.

However, not everyone has a positive attitude towards this software. Claudia, 20, who studies "health, environment and societies", sometimes feels disadvantaged.

She says: Sometimes I feel disappointed, like in modern languages modules, when I know for sure that I wrote everything from scratch and worked hard to get it done, and then I hear about others who just used ChatGPT and ended up getting much higher grades.

Students also fear the consequences if the chatbot disappoints them.

“I’m afraid of making mistakes and plagiarizing,” says Eva, 20, who is studying “health and environment” at University College London. Instead, she feeds her revision notes into ChatGPT and asks it to ask questions to test her knowledge.

“Of course it’s a little annoying, when you hear, ‘Oh, I got this grade,’” she says. “And you think, ‘Oh, you used ChatGPT to get that.’ [But] if others want to use AI now and then not know anything about the subject, that’s their problem.”

How should universities respond?

Universities, somewhat belatedly, are trying to draft new ethical codes and clarify how AI can be used depending on the course, module or type of assessment.

Approaches vary widely. Many universities allow the use of AI for research purposes or to help with spelling and grammar, but some prohibit it altogether. Penalties for violating the rules range from written warnings to expulsion.

“Universities are in the position of someone trying to close the barn door after the horse has left,” says an adjunct lecturer at a Russell Group university, and that our University is only now responding to AI by setting policies, such as which assessments do not allow its use.

There are some obvious signs of robot-generated writing that the professor notices: If I see a paper that's loaded with big words or lots of adjectives, I start to get suspicious.

Some students are certainly getting caught. Data obtained by Times Higher Education shows that cases of AI-related misconduct at Russell Group universities are on the rise as AI becomes more mainstream. At the University of Sheffield, for example, there were 92 suspected cases of AI-related misconduct in the 2023–24 academic year, with 79 students being disciplined. This compares to just 6 suspected cases and 6 disciplined in 2022–23.

But Palmer says many universities have become overly reliant on AI software like Turnitin, which compares student work to billions of pages online to detect potential plagiarism. Turnitin assigns a “similarity score,” the percentage of text that matches other sources. The company itself says the results shouldn’t be used in isolation.

“The burden of proof falls on the university to decide whether, in all likelihood, the student cheated, but that burden is quite low compared to a criminal case,” Palmer says.

Medical and biomedical science students appear to be the most vulnerable to the allegations, according to Palmer, because they often memorize technical definitions and medical terminology directly from AI.

The case of Andrew Stanford illustrates how complex this problem can be. In 2023, Stanford, 57, was accused by the University of Bath of using AI to cheat during his first-year exams. He had paid £15,000 to enrol on an MSc in applied economics (banking and financial markets) from his home in Thailand. However, nine months into his degree, he was accused of using AI to formulate answers in the exam. It is not clear how the university came to this conclusion.

Stanford insists the paragraphs in question were his own work. He searched popular artificial intelligence applications to see if there was any similar wording to his, but found nothing, he says. However, two months later, in November 2023, he was informed that he had been found guilty and would be given a 10 percent deduction from his grade.

“I didn’t mind the 10 percent deduction at all, but I did mind the fact that I would be left with a note for academic misconduct,” says Stanford, who teaches math and economics in Thailand. “It was incredibly frustrating for me, when I hadn’t done anything wrong. It felt like an unfair judgment.”

Stanford, who will complete his two-and-a-half-year master's degree at Bath later this year, took his complaint to the Independent Higher Education Arbitration Office. He was found not guilty this month.

“Students will need these skills”

The risk to students, and universities, is very great.

“Universities are facing an existential crisis,” says Sir Anthony Seldon, former chancellor of the University of Buckingham. But if the challenges are overcome, this could also be an opportunity.

“AI could be the best thing that ever happened to education, but only if we get ahead of the flaws it brings. And the biggest problem right now is cheating. Generative AI is improving faster than the software used to detect it. It can be personalized to the user’s style, which means even a very good teacher will have a hard time spotting it. The vast majority of students are honest, but it’s very hard not to cheat when you know others are,” he says.

Some academics have proposed the return of proctored exams and the submission of handwritten papers as a solution. But Seldon doesn’t think the solution is to move from assignments to exams, because they don’t teach students great life skills. Instead, he says there should be more focus on seminars where students are encouraged to “think critically and collaboratively.”

Professor Paul Bradshaw, senior lecturer in data journalism at Birmingham City University, says AI is a "massive problem" for lecturers who have traditionally based assessments on students' ability to absorb text and draw their own conclusions.

However, he believes it is essential that universities teach students how to use AI critically, understanding its benefits and drawbacks, rather than banning it.

“You have a group of students who don't want to know anything about AI. The problem for them is that they're going to enter a job market where they're going to need these skills. Then you have another group who are using it but they're not telling anyone and they don't really know what they're doing. I think we're in a very uncomfortable situation where we're having to adapt as we go, and you're going to see a lot of mistakes, from students, from educators, and from technology companies. AI has the potential to either advance education or destroy it,” he says.

Latest news

Five bodies of skiers found near Swiss resort

2025-05-25 17:27:23

Home loan, shake hands!

2025-05-25 17:09:39

The court leaves "Akili" and 5 others in prison! One is released from the cell

2025-05-25 16:39:14

The rain is leaving, next week starts with clear weather

2025-05-25 15:59:54

How to prevent hormonal changes, the most necessary tips

2025-05-25 15:27:25

The Times Analysis: Will universities survive ChatGPT?

2025-05-25 15:16:08

With drugs and high speed, Albanian loses his life in an accident in Italy

2025-05-25 14:40:36

Israeli strikes kill 20 people in Gaza, including a journalist

2025-05-25 13:02:47

52-year-old dies at work in Tirana, boiler falls on his head

2025-05-25 12:13:07

The session to constitute the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 21st time

2025-05-25 11:51:18

New details emerge from the explosion in Berat, two brothers wanted

2025-05-25 11:23:38

Last tributes to Piro Milkani, the director is being buried in Sharra today

2025-05-25 11:01:54

Foreigners pay more for rent than Germans

2025-05-25 10:41:28

Arlind Kajoshi, suspected of beating Vladimir Bruçi, arrested in Shkodra

2025-05-25 10:32:42

Attempted to kill 58-year-old man with axe in Fier, father arrested, son wanted

2025-05-25 10:05:15

Explosion with explosives in a bar in Berat

2025-05-25 09:42:00

Private railway management

2025-05-25 09:18:32

A car caught fire on the Fier-Lushnje road

2025-05-25 08:41:45

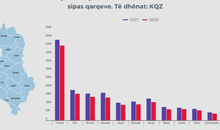

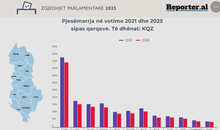

Voters who were absent in the parliamentary elections

2025-05-25 08:37:28

Weather today: Cloudy and temporary rain in some areas

2025-05-25 08:17:25

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-05-25 08:02:15

Shuhet në moshën 86-vjeçare regjisori i njohur Piro Milkani

2025-05-24 21:56:38

Kujdes nga mashtrimet online, si teknologjia nxit krimet financiare

2025-05-24 21:32:33

Opposition's denunciations, Xhaferri: We expect the US to listen to us

2025-05-24 20:48:06

How did PSD "capture" over 50% of the votes in rural areas?

2025-05-24 20:29:54

The Albanian woman with the s*x went to meet her husband in Koridalos prison

2025-05-24 20:09:15

Ancelotti says goodbye to Real Madrid in tears: I love you with all my heart!

2025-05-24 19:49:08

Poisoning in Gramsh, parents of children warn of protest

2025-05-24 19:21:36

Taulant Xhaka retires from football

2025-05-24 18:53:35

Incident in the north, Serbia issues arrest warrant for Kosovo police officer

2025-05-24 17:59:24

SPAK conducts inspections at Tirana Municipality, 5 phones seized

2025-05-24 17:19:23

FIFA President congratulates Egnatia on the championship title

2025-05-24 17:00:15

Boçi: The elections were annulled, the DP will continue the fight

2025-05-24 16:06:58

Man reports to police: Wife took my son and ran away, I'm asking for help

2025-05-24 15:45:55

France and Germany with a "non-paper" for Republika Srpska

2025-05-24 15:29:29

Beware of online scams! Here's how technology fuels financial crimes in Albania

2025-05-24 14:53:33

The US military "landed" in Kosovo as part of "Defender Europe 25"

2025-05-24 14:42:19

BIRN Analysis: Voters who were absent in the parliamentary elections

2025-05-24 11:19:40

Bus collides with municipal police car in Fier, 6 injured

2025-05-24 09:25:01

Foreign exchange, May 24, 2025

2025-05-24 09:07:27

With rain and storms, get to know the weather forecast

2025-05-24 08:32:03

What do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-05-24 08:17:04

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-05-24 08:00:34

Tirana Lake Park, a campaign center for Noizy. The signatory is silent

2025-05-23 21:55:02

What's happening in Gaza, the struggle for survival in times of war in pictures

2025-05-23 21:02:54

DW: Germany strengthens the return of illegal migrants!

2025-05-23 20:39:57

Knife attack at Hamburg train station, 12 injured

2025-05-23 19:54:58

120 children go missing every year in Albania, 12 still missing in 30 years

2025-05-23 19:35:35

US court suspends order banning Harvard from admitting foreign students

2025-05-23 19:22:41

Zodiac signs that become luckiest after the third decade of life

2025-05-23 19:19:06

Igli Tare officially appointed as Milan's new Sporting Director

2025-05-23 19:01:12