Flash News

Flash News

Accused of murder due to blood feud, 48-year-old arrested in England

SPAK conducts searches at Ergys Agas' businesses and residences, seizes two vehicles

Members of criminal organizations! 3 Albanians extradited from Dubai today

Berisha warns of new facts about the electoral farce: Don't forget that the laptop hasn't started talking yet

Berisha to gather political leaders tomorrow

Albanians are not indebted to Italy for its "hospitality" in the 1990s

The protocols signed by Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni last November, according to which the government in Tirana will allow Italy to build camps for immigrants on Albanian territory, have generated various negative reactions. The issue contains some politically dangerous and morally low features that deserve attention. One is the reasoning given by Rama to justify the agreement. According to him, the main reason for giving the national territory is a kind of "debt" that Albanians owe to Italy for the way it hosted them in the early 1990s. Archival documents show that Italy's "hospitality" was a short-lived policy that served them interests of the state contingent.

Emigration to Italy begins in the 1980s

After ending relations with China in the late 1970s, communist Albania opened up to Western European countries such as Italy. The countries were driven to cooperate for opposite reasons. For the Albanians, it was a matter of economic necessity. For Italy it was a means to expand its influence in the Balkans. Archival data show that over 2,000 Italians traveled to Albania in 1983 as tourists, journalists, businessmen, professionals and diplomats. Italians and other Western Europeans were seen in Tirana, Durrës and other tourist spots. Then, as today, mobility regimes were asymmetric. It was easier for Italians to go to Albania than vice versa.

The first Albanians who arrived in Italy in large numbers were from Kosovo. In April 1984, the right-wing newspaper Il Tempo reported that Italian authorities had granted asylum to many immigrants from Eastern Europe, most of whom, 444, came from Albania. Albanian Foreign Minister Reiz Malile denied the information, asserting that they did not come from Albania, but from Kosovo, where they had been persecuted. They stated that they were born in Albania because they were afraid of being sent back, given the good relations between Rome and Belgrade. Similar events were recorded in November 1988, when 43 Kosovars sheltered in the Kapua refugee camp declared that they were of Albanian origin.

Unlike Yugoslav citizens, Albanians could not obtain visas unless they had strong family or professional reasons. Crossing the border illegally was dangerous because the state reacted with ferocity. However, with the death of Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha in April 1985, people became more courageous. On December 12, 1985, six members of the Popa family, four women and two men, evaded checks and entered the Italian embassy, where they sought political asylum. The event provoked a diplomatic crisis. Albanian authorities declared that the Popes were former fascist and Nazi collaborators and demanded that Italy extradite them. The Italians refused. Foreign Minister Giulio Andreotti cited the protection of "human rights" as the main reason for the refusal.

The situation remained tense for months, as the Albanian authorities did not allow the Popa family to go to Italy. The cars of Italian diplomats were searched and chased for fear that the Popes might escape. Some Italian politicians wanted a firmer stance from their government. The exponents of the neo-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI, which is now called "Fratelli d'Italia", (Brothers of Italy) wanted to break diplomatic relations with Albania, because it did not allow Popes to emigrate to Italy. The popes lived in the embassy for almost five years. They were finally allowed to leave in May 1990. This inspired many Albanians to enter foreign embassies in July 1990.

The Popa family brought the issue of human rights in Albania to the center of attention in Italy. In 1987, Italian associations sent a petition to Tirana demanding the release of political prisoners and the introduction of other freedoms. This political atmosphere may have encouraged others to seek refuge in the neighboring state. In August 1988, a lyric singer studying at the Turin Conservatory informed the embassy that she had decided to stay in Italy because she wanted to marry an Italian. At the end of September 1988, Elvira Gjezi, who later became known by her pseudonym Elvira Dones, disappeared from her hotel in Milan. She was there to participate in a film fair with colleagues from the film production company "Kinostudio".

Migratory trends in the Adriatic have rarely been a one-way process: people from different countries tried to enter Albania. For example, in August 1982, a 15-year-old boy from Morocco hid inside an Albanian ship in the port of Nador and landed in Durrës. In the late 1980s, some Italians wanted to move to Albania for political reasons. The Albanian authorities considered these requests embarrassing and rejected them.

In the late 1980s, workers in the port of Durrës paved the way for the emigration by ship of the 1990s. In February and March 1987, two sailors of the ships Teuta and Korabi landed in the port of Ravenna and escaped. The government of Tirana asked the Italians to return them. The Italians ignored the request. They later informed the Albanian government that the sailors had immigrated to the US. On December 20, 1988, workers at the port of Ravenna found a man hiding inside the Albanian ship 6 February. He had a passport with him. The workers denounced the ship's crew because they forced the man back on board the ship after he had disembarked. The police asked the man what happened. He, perhaps threatened by the ship's crew, replied that he had accidentally fallen below deck because he was drunk. The Italian authorities allowed the ship to return with the person in question on board.

On January 6, 1989, nine people hijacked the Ducati and headed for the Italian coast. The plan was carried out by captain Enver Meta and sailor Bardhyl Vogli. The hijackers seized seven crew members who did not want to emigrate and held them captive for the entire voyage. After arriving in Brindisi, they applied for political asylum. The Albanian government tried to convince the Italian authorities to release the fugitives, portraying them as terrorists, drug dealers and mobsters. However, only one of them had a criminal record and it was not related to terrorism or drugs. Italian authorities arrested the captain and sailor for hijacking the ship and the people on board. Six others were sheltered by Caritas.

Captain Enver Meta exposed to the local media the bad social conditions and the lack of political freedoms in Albania. On January 20, 1989, Meta and Vogli were released by the Brindisi court and transferred to a refugee camp. The judges argued that Albania's lack of political freedoms was a known fact and that the country did not adhere to international agreements for the protection of human rights. The court affirmed that Meta and Vogli had escaped from a situation that violated their individual rights, such as freedom to emigrate, freedom of thought and freedom of belief. The lawyer employed by the Albanian state suspected that the sentence was a "political decision".

The policy for Albanian immigrants is toughened after the fall of the dictatorship

Some civil society activists protesting in front of the Constitutional Court of Albania against the migrant agreement with Italy. Photo: BIRN. Some civil society activists protesting in front of the Constitutional Court of Albania against the migrant agreement with Italy. Photo: BIRN.

In July 1990, over 800 Albanians entered the Italian embassy in Tirana. They all moved to Italy. In December 1990, the Albanian dictatorship officially fell. Between February and March 1991, over 20,000 people reached Italian shores by boat from the port of Durrës. At that time, Rome's attitude towards Albanian immigrants began to change.

In March 1991, over 18,000 Albanians applied for asylum, but only 672 were accepted. In June 1991, the spokesman of the Italian Foreign Ministry claimed that Albania had taken important steps towards democratization and respect for human rights. The change in the political framework justified more restrictive policies towards Albanian immigrants. However, this assessment did not take into account the actual situation on the ground. Albania was then challenged by the worst political and economic crisis since World War II. The state could not protect "human rights". Legal migration was almost impossible for most Albanians as they did not meet the requirements needed to obtain visas.

"Hospitality" for Albanians began in the late 1980s, with a few scattered cases of people who went to Italy and who in many cases emigrated to the USA or elsewhere. This phase lasted until February-March 1991, when a large number of Albanians went to Italy by ship. Albanians who tried to emigrate in the following months, such as those who traveled on the ship Vlora, were not welcomed. Most of the passengers were taken to Bari's old stadium, where they were kept without access to water, food and toilets. While the police tried to keep them inside the stadium, according to some sources, ordinary people organized "hunting" campaigns (caccia all'albanese) to catch those who escaped. The Italian state took the "painful" decision to repatriate all the people who arrived on the Vlora ship.

Figura të opozitës kritikuan qeverinë për mënyrën se si ajo i trajtoi emigrantët shqiptarë. Bianca Gelli, nga Partia Komuniste, dërgoi një raport në OKB për të ekspozuar “trajtimin çnjerëzor” të tyre. Pino Rauti, i MSI-së, u shqetësua nga pamjet e shqiptarëve në stadium, sepse kjo i risolli në kujtesë përvojën e tij si i burgosur në një kamp përqendrimi. Në vitet e para të tranzicionit, shqiptarët shiheshin si viktima të komunizmit dhe kishin keqardhjen e politikanëve të ekstremit të djathtë me ndjenja nostalgjike si Rauti. Mirko Tremaglia, një tjetër eksponent i MSI-së, bëri një propozim me nëntone neo-koloniale. Ai përmendi një plan investimi në Afrikën e Veriut dhe Shqipëri të konceptuar nga partia e tij për të parandaluar emigrimin. Këto synime të këtij plani tingëllojnë të ngjashme me nismën e fundit të kryeministres Meloni, Piano Mattei. Duke evokuar të kaluarën koloniale të Romës, Tremaglia pohoi se Italia kishte lidhje të forta me Shqipërinë përpara komunizmit. Ai sugjeroi se Italia duhet të kishte marrë një mandat për menaxhimin e ndihmës në Shqipëri, sepse ngjarjet në Somali – një tjetër ish-koloni italiane – treguan se nuk mund t'u besohej qeverive vendore.

Ngjarjet në Bari përcaktuan tonin për trajtimin e shqiptarëve në Italinë e viteve 1990. Shfaqja e skandaleve të korrupsionit në vitin 1992 spastroi shumë politikanë italianë që merreshin me Shqipërinë në vitet e para të tranzicionit. Megjithatë, situata e emigrantëve shqiptarë nuk u përmirësua. Qeveritë e reja, qofshin ato të majta apo të djathta, vazhduan të zbatonin politika të rrepta migratore dhe shqiptarët u detyruan ta kalonin detin me mjete të paligjshme duke e vënë jetën e tyre në rrezik ekstrem. Shtypi dhe policia shtuan mbikëqyrjen ndaj tyre dhe i përdorën shqiptarët si koka turku. Shqiptarët punonin dhe ende punojnë me rroga më të ulëta dhe shpesh pa kontribute shoqërore. Në shumë raste, shteti nuk i mbrojti ata nga punëdhënës dhe trafikantë lakmitarë, sepse nuk pranoi t'u jepte dokumente.

Një mit i krijuar për ta paraqitur Italinë si “shpëtimtare”

Narrativa e “mikpritjes” synon të nxisë mitin e vjetër të Italisë si “shpëtimtarja” e shqiptarëve. Ky mit shërben për t'i bërë shqiptarët të ndihen fajtorë dhe në borxh ndaj shtetit italian dhe në të njëjtën kohë për të fshehur e harruar shfrytëzimin të cilit i është nënshtruar shumica e tyre.

No one should feel indebted to Italy or listen to what demagogic leaders like Rama and Meloni say about Albanian-Italian relations. It is Italy that should feel indebted to the Albanians, given the human and material costs of the imperialist policy and the wars it waged in Albania. The camps and the expansionist framework of Italy's foreign policy risk poisoning the relations between Albanians and Italians. In addition to reflecting the racist attitude of the Italian far-right towards Albanians and other immigrants, they evoke the concentration camps that Italy built during World War II in Albania. I think that Albanians and Italians should oppose their construction./ BIRN

Latest news

Vote recount in Tirana, Kaso: We did not have the 14th mandate as our objective

2025-06-19 22:44:53

Noka: Policemen were running from morning to night for SP votes

2025-06-19 21:31:03

The three zodiac signs that will be disappointed in love this month

2025-06-19 21:18:48

Accused of murder due to blood feud, 48-year-old arrested in England

2025-06-19 21:06:57

Vasili releases video: Tirana-Kashar segment full of gravel, no workers around!

2025-06-19 21:00:48

Tirana without a coach, four names considered for the white-and-blue bench

2025-06-19 20:21:12

Rinderpest/ A new outbreak appears in Shkodra, 200 sheep affected

2025-06-19 20:01:50

Scientists raise the alarm: Earth risks exceeding the 1.5°C warming limit!

2025-06-19 19:37:44

"Fiscal Peace" without consultation with the EU, Brussels concerned

2025-06-19 19:05:23

Trump signs executive order extending TikTok ban in US for another three months

2025-06-19 19:03:35

A special Task Force on immigration is established in cooperation with Italy

2025-06-19 18:23:58

Drug trafficking gang busted in Italy, 25 people arrested, including Albanians

2025-06-19 18:18:33

AMF denounces a suspicious cryptocurrency investment platform

2025-06-19 18:06:07

Technology as a tool of war between Israel and Iran

2025-06-19 17:27:54

EU divided over Israel's right to bomb Iran

2025-06-19 16:10:42

Analysis/ How is Russia spreading propaganda in the Albanian language?

2025-06-19 15:49:18

Session in the Criminal Court, MP Qani Xhafa is fined

2025-06-19 15:33:30

Members of criminal organizations! 3 Albanians extradited from Dubai today

2025-06-19 15:20:04

Lufta/ Zelenskyy bën thirrje për rritjen e presionit ndaj Rusisë

2025-06-19 14:56:02

Netanyahu warns Iran after attacks on Israeli hospital

2025-06-19 14:34:53

Attempted to enter Albania with false documents, 25-year-old arrested

2025-06-19 14:18:20

Psychology explains what happens in the brain of a person contemplating suicide

2025-06-19 14:01:25

These are the coldest zodiac signs

2025-06-19 13:45:18

Albanian man dies in hospital after accident in Italy

2025-06-19 13:02:45

Berisha to gather political leaders tomorrow

2025-06-19 12:32:23

Iran confirms meeting with representatives of Britain, Germany and France

2025-06-19 12:11:33

The constitution of the Kosovo Assembly fails for the 34th time

2025-06-19 11:30:28

Albania's nuclear bomb!

2025-06-19 10:52:02

Prej 4 ditësh e zhdukur, humb gjurmët adoleshentja shqiptare në Greqi

2025-06-19 10:33:11

Choosing a child's name, expert reveals three key factors

2025-06-19 10:29:17

Another request for release from house arrest

2025-06-19 09:49:14

Who is the 18-year-old who stole the crown of "Miss Albania 2025"?

2025-06-19 09:41:37

Arrestohet punonjësi i shërbimeve funerale, vidhte në varrezat e Korçës

2025-06-19 09:13:03

Foreign exchange, June 19, 2025

2025-06-19 09:00:33

Montenegrin arrested in Spain for involvement in a structured criminal group

2025-06-19 08:55:04

BBC: Trump has approved the plan to attack Iran

2025-06-19 08:45:01

Draft reports from Brussels expose 'government facade' towards integration

2025-06-19 08:31:21

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-19 08:17:33

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-19 07:49:56

Zhulali: EU does not tolerate basic standards, membership is a political process

2025-06-18 22:40:09

Recount process/Këlliçi: DP seeks 14th mandate in Tirana

2025-06-18 22:11:20

Hell in the Gjadri camp, 45 attempted injuries and violent protests

2025-06-18 21:49:49

Israel strikes National Police headquarters in Iran, several injured reported

2025-06-18 21:29:11

Why World War III is 'speaking', and the Albanian PM Rama is silent

2025-06-18 20:08:03

Avoid drying towels in the sun, here's how to keep them soft

2025-06-18 20:07:53

Cannabis legalization in Albania, new law, old risks

2025-06-18 19:39:54

Pope Leo XIV calls for peace: Advanced weapons are temptations we must reject

2025-06-18 19:22:29

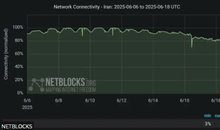

Iran faces near-total internet blackout

2025-06-18 19:07:09

INSTAT: Heart diseases, the leading cause of death in Albania during 2024

2025-06-18 18:05:33