Flash News

Flash News

Drenova prison police officer arrested for bringing drugs and illegal items into cell

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

Alfred Lela

In the novels of Latin American authors, abusive caudillos, at the end of their age and career, turn into impotent bedwetters. At the end of the Cold War, the Romanian dictator Ceausescu, who ruled with an iron hand for several decades, had a funny death. Manuel Noriega also met a tragicomic end. In the context that this Op-Ed wants to illustrate, by ridiculous, we will understand the condition or the end of people and political regimes that have claimed one thing for a long time and ended up with the complete opposite. Their decline concerning their power and claims is seen as ridiculous.

In this respect, even Edi Rama's regime is becoming ridiculous, which means it is nearing the end. Rama started as prime minister, demolishing some buildings and publishing photos of the mess found in the basement of the government headquarters. It was his way of saying that, with the Renaissance at the helm of affairs, the chaos of the previous democrat government would end, law and order would prevail, and aesthetics would be the face of things.

Thus, he invented the Urban Renaissance, removed the fence in front of his office, and planted installations in its garden to show openness and orientation toward beauty. On the sides of the Tirana-Durrës highway, he planted palm trees and some strange concrete mini-domes.

People thus experienced what can be called a phase of shock, which came both from Rama's methodology and the language chosen to convey it. This mixture of Jacobinism and Sanguinism overcame the initial surprise, and with time passing, the public became indifferent. After passing the stage of wanting to shock, Rama entered the second stage, which can be called reformism. The most significant claims are related to the Justice Reform, an annex thereof, vetting in the police force, and the deflation of the big belly of the policemen. Without forgetting a leitmotif, which he had carried over from the electoral campaign, with the illumination of a cliché that, like all clichés, is both banal and popular: "the fault is not with the individual, but with the system".

Eleven years later, it can be said, now with certainty, that Rama's regime is in its last, concluding phase. Three illustrative examples from the previous week prove that the Renaissance has passed from the shock stage to the reformer stage and is now prone to the ridiculous.

The first case is related to the arrest by SPAK of a senior director under the Ministry headed by Rama's deputy, B. Balluku. After a search of the apartment, several works of art were found at the director's house, which were reported as expensive (this is a well-known method of the criminal world to hide illegal assets or launder dirty money: buying expensive paintings from famous authors). The claim of the government's director was fantastic: I made the paintings myself. Of course, it is a claim from desperation because if the controlling policemen do not know about art, SPAK, even though there may not be people so elevated in the workings of culture, it's their job to hire art experts to assess such work.

The second case is even more delightful. The police announced that they had deported a wanted person from Dubai; they also showed the footage when he got off the plane in handcuffs. The next day, the 'extradited' said the exact opposite. He had returned from Dubai voluntarily and handed himself over to the police when he landed in Rinas. The police handcuffed him and put him on the stairs of the plane from where they had asked him to get off so that they could photograph him and share this 'success' with the media.

The third case belongs to a janitor who made a living by cleaning the houses of those with better financial opportunities (read: people from Rama's administration). One of them was Ada Klosi, a former high official, in whose apartment the janitor and her son stole 500,000 euros. At the end of the investigation, the Prosecutor's Office demanded that the thief of taxpayers' money be punished with 1.5 years in prison, while the janitor who stole the stolen money would be sentenced to 4.8 years. With simple logic, the amount stolen was the same for the former official and the janitor, i.e., 500,000 euros. The only difference is that one was involved in abuse of power and public office. A. Klosi abused her duty as a public official, while Dobi abused her 'duty' as a janitor. In any case, the burden of responsibility and guilt should have been heavier for the former official.

These are just three episodes that have surfaced and illustrate the banality of evil, i.e., acclimatization by the government and administration to theft, corruption, and distortion of the truth through propaganda at any price.

From the phase of shock to reformism, Rama's regime has become ridiculous. Of course, this is no laughing matter because the public bears the burden.

Latest news

Second hearing on the protected areas law, Zhupa: Unconstitutional and dangerous

2025-06-30 22:18:46

Israel-Iran conflict, Bushati: Albanians should be concerned

2025-06-30 21:32:42

Fuga: Journalism in Albania today in severe crisis

2025-06-30 21:07:11

"There is no room for panic"/ Moore: Serbia does not dare to attack Kosovo!

2025-06-30 20:49:53

Temperatures above 40 degrees, France closes nuclear plants and schools

2025-06-30 20:28:42

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

2025-06-30 20:13:54

Turkey against the "Bektashi state" in Albania: Give up this idea!

2025-06-30 20:03:24

Accused of sexual abuse, producer Diddy awaits court decision

2025-06-30 19:40:44

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

2025-06-30 18:44:12

Tourism: new season, old problems

2025-06-30 18:27:23

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

2025-06-30 17:51:44

Almost free housing: East Germany against depopulation

2025-06-30 16:43:06

Hamas says nearly 60 people killed in Gaza as Trump calls for ceasefire

2025-06-30 16:14:15

Drownings on beaches/ Expert Softa: Negligence and incompetence by institutions!

2025-06-30 16:00:03

European ports are overloaded due to Trump tariffs

2025-06-30 15:30:44

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

2025-06-30 15:19:54

Lezha/ Police impose 3165 administrative measures, handcuff 19 drivers

2025-06-30 14:55:04

Young people leave Albania in search of a more sustainable future

2025-06-30 14:47:52

Record-breaking summer, health threats and preventive measures

2025-06-30 14:36:19

Constitution of the Parliament, Osmani invites political leaders to a meeting

2025-06-30 14:07:54

Heat wave 'invades' Europe, Spain records temperatures up to 46 degrees Celsius

2025-06-30 13:42:02

Accident in Vlora, car hits 2 tourists

2025-06-30 13:32:16

Kurti confirms participation in today's official dinner in Skopje

2025-06-30 13:03:27

Fight between 4 minors in Kosovo, one of them injured with a knife

2025-06-30 12:38:45

Report: Teenage girls the loneliest in the world

2025-06-30 12:20:40

Commissioner Kos and Balkan leaders meet in Skopje on Growth Plan

2025-06-30 12:07:59

Wanted by Italy, member of a criminal organization captured in Fier

2025-06-30 11:55:53

Hundreds of families displaced by wave of Israeli airstrikes in Gaza

2025-06-30 11:45:17

Zenel Beshi: The criminal who even 50 convictions won't move from Britain

2025-06-30 11:23:19

A new variant of Covid will circulate during the summer, here are the symptoms

2025-06-30 11:14:58

"Partizani" case, trial postponed to July 21 at the Special Court

2025-06-30 10:41:05

Uncontrolled desire to steal, what is kleptomania, why is it caused

2025-06-30 10:30:08

Requested change of security measure, hearing for Malltez postponed to July 7

2025-06-30 10:24:32

Output per working hour in Albania 35% lower than the regional average

2025-06-30 09:54:35

The trial for the "Partizani" file begins today

2025-06-30 09:27:57

22 fires in the last 24 hours in the country, 2 still active

2025-06-30 09:21:28

How is the media controlled? The 'Rama' case and government propaganda

2025-06-30 09:13:36

German top diplomat: Putin wants Ukraine to capitulate

2025-06-30 09:00:07

Foreign exchange, how much foreign currencies are sold and bought today

2025-06-30 08:44:38

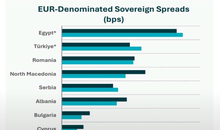

Chart/ Sovereign risk for Albania from international markets drops significantly

2025-06-30 08:26:38

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you?

2025-06-30 08:11:44

Clear weather and passing clouds, here is the forecast for this Monday

2025-06-30 07:59:32

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-30 07:47:37

Milan make official two departures in attack

2025-06-29 21:57:23

6 record tone

2025-06-29 21:30:46

4-year-old girl falls from balcony in Lezha, urgently taken to Trauma

2025-06-29 21:09:58

Assets worth 12 million euros seized from cocaine trafficking organization

2025-06-29 19:39:43

Fire in Durrës, Blushi: The state exists only on paper

2025-06-29 19:17:48

Fire endangers homes in Vlora, helicopter intervention begins

2025-06-29 18:27:51

France implements smoking ban on beaches and parks

2025-06-29 18:02:08

England U-21 beat Germany to become European champions

2025-06-29 17:42:49

Trump criticizes Israeli prosecutors over Netanyahu's corruption trial

2025-06-29 17:08:10

Street market in Durrës engulfed in flames

2025-06-29 16:52:57

UN nuclear chief: Iran could resume uranium enrichment within months

2025-06-29 16:03:24

Albanian man dies after falling from cliff while climbing mountain in Italy

2025-06-29 15:52:01

Another accident with a single-track vehicle in Tirana, a car hits a 17-year-old

2025-06-29 15:07:15

While bathing in the sea, a vacationer in Durrës dies

2025-06-29 14:54:01

Sentenced to life imprisonment, cell phone found in Laert Haxhiu's cell

2025-06-29 14:26:40

77 people detained in protest, Vučić warns of new arrests

2025-06-29 14:07:46

From a hospital for children to a prison for politicians

2025-06-29 13:34:02