Flash News

Flash News

Drenova prison police officer arrested for bringing drugs and illegal items into cell

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

Alfred Lela

Australian professor Mark Burry called Antoni Gaudí 's Sagrada Familia 'the first cathedral on Mars,' which means here not only a magnificent building but also out of place. It may sound hyperbolic to say that Ismail Kadare was such a 'cathedral on Mars'; with the deed more than with the personality, in Albania of 45 years of dictatorship and 30 years of democracy.

He entered Albanian literature at a time when three main currents and a dozen literary efforts stood out in its landscape, starting from folk songs, parody, and especially the light industry of poetry. All three significant currents can be considered engaged literature. The first is the Catholic literature of Shkodra (or that of Arbëresh in Italy), which builds through Christian-moral-patriotic commitment, with some rare exceptions such as de Rada, who writes a mainly lyrical poem, where nationalism is manifested through longing for the homeland.

The second is what can be described as the iconoclastic engagement or a new world, represented more distinctly by Migjeni and some other less critical authors of the time (who did not stand the test of time).

The third would be the ruling current in Albanian literature, the well-known socialist realism, which began its journey a little earlier than enfant terrible Ismail Kadare entered Albanian literature in the early 60s.

Kadare's literary genius is the understanding that he should not have been in these currents. To put it with Gaudí, in a Barcelona with many churches, transgressions, and claims, the 'first cathedral on Mars' had to be built. Kadare's work, from the first poems of boyish shyness to the shocking novels and essays of his mastery, is the cathedral in Mars that he raised for Albanians and the world. Just at the time when Albania's churches were demolished, its literature was trashed, and individual freedoms and human rights were restricted. Ismail Kadare thus created a watch of his own for Albania, the watch he crafted with care and Swiss finesse, thanks to a talent that seemed to have been given to him as an order from the heights - for which he would even build this cathedral. In this sense, mystical or divine, Kadare's work is a communication with and from above, so the comparison with the cathedral is also appropriate. He introduced music and image into Albanian literature, two of the assets of a cathedral.

Kadareja made an early break with socialist realism, or the Soviet style in literature, which he despised because 'it was full of hope, spring and joy that make my mouth open'. The establishment of literature that ran parallel to and simultaneously against, contrasting with the mixed and committed socialist realism of the League of Writers, is the high service that Kadare did to his nation and his language. The reward of this difference, of this cathedral, of that something Oscar Wilde calls 'every beautiful effect creates an enemy,' Kadareja would often give, just like the character with the vulture in his homonymous novel.

Ismail Kadare became a liberating and suffocating writer for Albania. Through text, ideas, and stylistic manipulation, he created a parallel and fantastic Albania. At the same time, strongly contrasting with almost all literary and cultural creativity in the country, he became what Emile Cioran describes so well: "We turn against the admired because he undertook to raise us to his level."

The cathedral, in this place that continues to be Mars, remains.

Latest news

Second hearing on the protected areas law, Zhupa: Unconstitutional and dangerous

2025-06-30 22:18:46

Israel-Iran conflict, Bushati: Albanians should be concerned

2025-06-30 21:32:42

Fuga: Journalism in Albania today in severe crisis

2025-06-30 21:07:11

"There is no room for panic"/ Moore: Serbia does not dare to attack Kosovo!

2025-06-30 20:49:53

Temperatures above 40 degrees, France closes nuclear plants and schools

2025-06-30 20:28:42

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

2025-06-30 20:13:54

Turkey against the "Bektashi state" in Albania: Give up this idea!

2025-06-30 20:03:24

Accused of sexual abuse, producer Diddy awaits court decision

2025-06-30 19:40:44

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

2025-06-30 18:44:12

Tourism: new season, old problems

2025-06-30 18:27:23

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

2025-06-30 17:51:44

Almost free housing: East Germany against depopulation

2025-06-30 16:43:06

Hamas says nearly 60 people killed in Gaza as Trump calls for ceasefire

2025-06-30 16:14:15

Drownings on beaches/ Expert Softa: Negligence and incompetence by institutions!

2025-06-30 16:00:03

European ports are overloaded due to Trump tariffs

2025-06-30 15:30:44

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

2025-06-30 15:19:54

Lezha/ Police impose 3165 administrative measures, handcuff 19 drivers

2025-06-30 14:55:04

Young people leave Albania in search of a more sustainable future

2025-06-30 14:47:52

Record-breaking summer, health threats and preventive measures

2025-06-30 14:36:19

Constitution of the Parliament, Osmani invites political leaders to a meeting

2025-06-30 14:07:54

Heat wave 'invades' Europe, Spain records temperatures up to 46 degrees Celsius

2025-06-30 13:42:02

Accident in Vlora, car hits 2 tourists

2025-06-30 13:32:16

Kurti confirms participation in today's official dinner in Skopje

2025-06-30 13:03:27

Fight between 4 minors in Kosovo, one of them injured with a knife

2025-06-30 12:38:45

Report: Teenage girls the loneliest in the world

2025-06-30 12:20:40

Commissioner Kos and Balkan leaders meet in Skopje on Growth Plan

2025-06-30 12:07:59

Wanted by Italy, member of a criminal organization captured in Fier

2025-06-30 11:55:53

Hundreds of families displaced by wave of Israeli airstrikes in Gaza

2025-06-30 11:45:17

Zenel Beshi: The criminal who even 50 convictions won't move from Britain

2025-06-30 11:23:19

A new variant of Covid will circulate during the summer, here are the symptoms

2025-06-30 11:14:58

"Partizani" case, trial postponed to July 21 at the Special Court

2025-06-30 10:41:05

Uncontrolled desire to steal, what is kleptomania, why is it caused

2025-06-30 10:30:08

Requested change of security measure, hearing for Malltez postponed to July 7

2025-06-30 10:24:32

Output per working hour in Albania 35% lower than the regional average

2025-06-30 09:54:35

The trial for the "Partizani" file begins today

2025-06-30 09:27:57

22 fires in the last 24 hours in the country, 2 still active

2025-06-30 09:21:28

How is the media controlled? The 'Rama' case and government propaganda

2025-06-30 09:13:36

German top diplomat: Putin wants Ukraine to capitulate

2025-06-30 09:00:07

Foreign exchange, how much foreign currencies are sold and bought today

2025-06-30 08:44:38

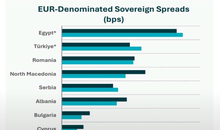

Chart/ Sovereign risk for Albania from international markets drops significantly

2025-06-30 08:26:38

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you?

2025-06-30 08:11:44

Clear weather and passing clouds, here is the forecast for this Monday

2025-06-30 07:59:32

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-30 07:47:37

Milan make official two departures in attack

2025-06-29 21:57:23

6 record tone

2025-06-29 21:30:46

4-year-old girl falls from balcony in Lezha, urgently taken to Trauma

2025-06-29 21:09:58

Assets worth 12 million euros seized from cocaine trafficking organization

2025-06-29 19:39:43

Fire in Durrës, Blushi: The state exists only on paper

2025-06-29 19:17:48

Fire endangers homes in Vlora, helicopter intervention begins

2025-06-29 18:27:51

France implements smoking ban on beaches and parks

2025-06-29 18:02:08

England U-21 beat Germany to become European champions

2025-06-29 17:42:49

Trump criticizes Israeli prosecutors over Netanyahu's corruption trial

2025-06-29 17:08:10

Street market in Durrës engulfed in flames

2025-06-29 16:52:57

UN nuclear chief: Iran could resume uranium enrichment within months

2025-06-29 16:03:24

Albanian man dies after falling from cliff while climbing mountain in Italy

2025-06-29 15:52:01

Another accident with a single-track vehicle in Tirana, a car hits a 17-year-old

2025-06-29 15:07:15

While bathing in the sea, a vacationer in Durrës dies

2025-06-29 14:54:01

Sentenced to life imprisonment, cell phone found in Laert Haxhiu's cell

2025-06-29 14:26:40

77 people detained in protest, Vučić warns of new arrests

2025-06-29 14:07:46