Flash News

Flash News

Drenova prison police officer arrested for bringing drugs and illegal items into cell

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

In an Albania that is depopulating, why is the prime minister campaigning with the promise of making it easier for young people to leave?

If Rama wants to be the prime minister who takes Albania into the European Union, he must first be the leader who makes Albania worthy of staying. That means building a country where an EU passport is a gateway - not an escape route. Because freedom is not just the ability to leave. It is also the right to hope, to build and to thrive - right where you are.

By ANDI BALLA

In his latest campaign for the upcoming parliamentary elections in May, Prime Minister Edi Rama has come up with an interesting idea: freedom through departure.

Rama is promising that Albania’s EU membership will happen by 2030. And of all the benefits that come with membership, he is focusing heavily on one thing he knows sells well to Albanian voters: the EU passport.

“Albania’s European passport… means the freedom to stay anywhere within the EU’s borders,” he said on March 29. “With an EU passport, young men and women from Albania will be able to study at EU universities with the same rights and fees as equal European students. Every Albanian will be able to work anywhere – from Stockholm to Lisbon, from Madrid to Warsaw – enjoying the same rights as Swedes in Sweden and Spaniards in Spain.”

It’s an appealing message, especially for the tens of thousands of Albanians who plan to emigrate each year. But for a country already crumbling under the weight of depopulation, it also borders on the surreal. Why is the leader of an aging and shrinking country openly campaigning on a promise that will make it easier for its young people to leave?

Albania’s demographic decline is no longer a future concern — it is an ongoing reality. The population has fallen by more than 14 percent since 2011. The birth rate has fallen to a record low of 1.21 children per woman, and almost every village, town, and city feels the emigration vacuum. The working-age population has been hit hardest, shrinking by 18.3 percent in just over a decade. Health care institutions are understaffed, schools are closing, and labor shortages now extend to every sector. Meanwhile, remittances from abroad are more of a lifeline than an investment. The

promise of an EU passport, then, resonates deeply with the public, not because they see a future in Albania, but because they don’t.

For years, Albania’s EU accession process seemed stuck in endless technocratic loops. Many lost faith. Now, with geopolitical changes like Russia’s war in Ukraine reshaping Europe’s priorities, the process has accelerated. At a recent roundtable, EU Enlargement Commissioner Marta Kos identified Albania and Montenegro as “frontrunners” in the Western Balkans and suggested that negotiations could be completed by the end of 2027.

But this vision comes with caveats. The reality is much more complex and less certain.

Opinions among EU member states differ widely on how quickly and under what conditions each Western Balkan country should be admitted. The main issue is that, under the EU’s unanimity rule, it only takes one member state to block or completely block the process. France and the Netherlands, for example, have consistently stressed the need for deep internal EU reforms before any enlargement.

Thus, even if Albania were to complete negotiations by 2027 - a very ambitious scenario - there is no guarantee that membership would follow by 2030. Enlargement has become as much about timing and trust as it is about technical readiness.

Moreover, Rama’s message is that he needs a supermajority, essentially consolidating whatever little power remains in the checks and balances in parliamentary life, so that Albanians can get that European passport. And that only he can deliver it. But the truth is that he cannot guarantee that. No leader can. And campaigning on a promise that may not materialize, while ignoring the urgent need to make Albania livable in the meantime, is a risky bet.

Worse, the underlying message seems to be: Albania’s biggest offer to its young people is a way out. The government has not introduced any comprehensive measures to keep its population growing. Incentives for young families are few. Housing is increasingly unaffordable, wages remain low, and trust in public institutions is low. When asked in a 2023 survey where they wanted their children to grow up, most Albanian parents chose “abroad.”

At the same time, Albania lacks what it desperately needs: a vibrant democracy. Under Rama’s leadership, the Socialist Party has consolidated power to an extent not seen in the post-communist era. The SP governs 9 out of 10 Albanians at the municipal level and holds a parliamentary majority that, critics warn, is sliding the country into a single-party system. Media freedom is in decline and the electoral system is skewed to favor incumbents, making it almost impossible for new political voices to gain ground.

This erosion of democratic competition – and indeed any real competition in many areas of life – from academia to business – further disenchants young voters. It is no wonder that, when given the chance, they choose to move to wealthier EU states.

To be clear, EU membership must remain a strategic goal. But it must be approached with clarity and humility. Full EU integration will open up borders – but unless it is accompanied by structural reforms at home, it will also empty Albania faster than ever before.

If Rama wants to be the prime minister who takes Albania into the European Union, he must first be the leader who makes Albania worth staying in. That means investing in healthcare and education, implementing serious anti-corruption reforms, supporting young families with meaningful social policies, and reviving democratic institutions. It means building a country where an EU passport is a gateway – not a lifeline.

Because freedom is not just the ability to leave. It's also the right to hope, to build, and to thrive - right where you are.

Latest news

Second hearing on the protected areas law, Zhupa: Unconstitutional and dangerous

2025-06-30 22:18:46

Israel-Iran conflict, Bushati: Albanians should be concerned

2025-06-30 21:32:42

Fuga: Journalism in Albania today in severe crisis

2025-06-30 21:07:11

"There is no room for panic"/ Moore: Serbia does not dare to attack Kosovo!

2025-06-30 20:49:53

Temperatures above 40 degrees, France closes nuclear plants and schools

2025-06-30 20:28:42

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

2025-06-30 20:13:54

Turkey against the "Bektashi state" in Albania: Give up this idea!

2025-06-30 20:03:24

Accused of sexual abuse, producer Diddy awaits court decision

2025-06-30 19:40:44

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

2025-06-30 18:44:12

Tourism: new season, old problems

2025-06-30 18:27:23

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

2025-06-30 17:51:44

Almost free housing: East Germany against depopulation

2025-06-30 16:43:06

Hamas says nearly 60 people killed in Gaza as Trump calls for ceasefire

2025-06-30 16:14:15

Drownings on beaches/ Expert Softa: Negligence and incompetence by institutions!

2025-06-30 16:00:03

European ports are overloaded due to Trump tariffs

2025-06-30 15:30:44

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

2025-06-30 15:19:54

Lezha/ Police impose 3165 administrative measures, handcuff 19 drivers

2025-06-30 14:55:04

Young people leave Albania in search of a more sustainable future

2025-06-30 14:47:52

Record-breaking summer, health threats and preventive measures

2025-06-30 14:36:19

Constitution of the Parliament, Osmani invites political leaders to a meeting

2025-06-30 14:07:54

Heat wave 'invades' Europe, Spain records temperatures up to 46 degrees Celsius

2025-06-30 13:42:02

Accident in Vlora, car hits 2 tourists

2025-06-30 13:32:16

Kurti confirms participation in today's official dinner in Skopje

2025-06-30 13:03:27

Fight between 4 minors in Kosovo, one of them injured with a knife

2025-06-30 12:38:45

Report: Teenage girls the loneliest in the world

2025-06-30 12:20:40

Commissioner Kos and Balkan leaders meet in Skopje on Growth Plan

2025-06-30 12:07:59

Wanted by Italy, member of a criminal organization captured in Fier

2025-06-30 11:55:53

Hundreds of families displaced by wave of Israeli airstrikes in Gaza

2025-06-30 11:45:17

Zenel Beshi: The criminal who even 50 convictions won't move from Britain

2025-06-30 11:23:19

A new variant of Covid will circulate during the summer, here are the symptoms

2025-06-30 11:14:58

"Partizani" case, trial postponed to July 21 at the Special Court

2025-06-30 10:41:05

Uncontrolled desire to steal, what is kleptomania, why is it caused

2025-06-30 10:30:08

Requested change of security measure, hearing for Malltez postponed to July 7

2025-06-30 10:24:32

Output per working hour in Albania 35% lower than the regional average

2025-06-30 09:54:35

The trial for the "Partizani" file begins today

2025-06-30 09:27:57

22 fires in the last 24 hours in the country, 2 still active

2025-06-30 09:21:28

How is the media controlled? The 'Rama' case and government propaganda

2025-06-30 09:13:36

German top diplomat: Putin wants Ukraine to capitulate

2025-06-30 09:00:07

Foreign exchange, how much foreign currencies are sold and bought today

2025-06-30 08:44:38

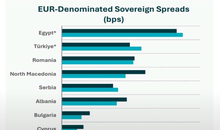

Chart/ Sovereign risk for Albania from international markets drops significantly

2025-06-30 08:26:38

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you?

2025-06-30 08:11:44

Clear weather and passing clouds, here is the forecast for this Monday

2025-06-30 07:59:32

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-30 07:47:37

Milan make official two departures in attack

2025-06-29 21:57:23

6 record tone

2025-06-29 21:30:46

4-year-old girl falls from balcony in Lezha, urgently taken to Trauma

2025-06-29 21:09:58

Assets worth 12 million euros seized from cocaine trafficking organization

2025-06-29 19:39:43

Fire in Durrës, Blushi: The state exists only on paper

2025-06-29 19:17:48

Fire endangers homes in Vlora, helicopter intervention begins

2025-06-29 18:27:51

France implements smoking ban on beaches and parks

2025-06-29 18:02:08

England U-21 beat Germany to become European champions

2025-06-29 17:42:49

Trump criticizes Israeli prosecutors over Netanyahu's corruption trial

2025-06-29 17:08:10

Street market in Durrës engulfed in flames

2025-06-29 16:52:57

UN nuclear chief: Iran could resume uranium enrichment within months

2025-06-29 16:03:24

Albanian man dies after falling from cliff while climbing mountain in Italy

2025-06-29 15:52:01

Another accident with a single-track vehicle in Tirana, a car hits a 17-year-old

2025-06-29 15:07:15

While bathing in the sea, a vacationer in Durrës dies

2025-06-29 14:54:01

Sentenced to life imprisonment, cell phone found in Laert Haxhiu's cell

2025-06-29 14:26:40

77 people detained in protest, Vučić warns of new arrests

2025-06-29 14:07:46