Flash News

Flash News

Drenova prison police officer arrested for bringing drugs and illegal items into cell

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

Lori E. Amy

I am a trauma theorist, not a cultural heritage specialist – I want to make that clear, because my activism in recent years to protect cultural heritage in Albania comes from my understanding that cultural heritage is important for healing the collective traumas from which the people and country are suffering.

I will say a few things about the collective traumas I see that need healing, but, first, I want to give you some examples of how Albania's cultural heritage can help with that healing.

Let's start with the historic city center. Within a scant few hundred meters, your rich heritage testifies to the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires as well as to the turn of the twentieth century and the period of modernity. This is an extraordinary treasure, hidden in plain sight — 700 years chronicling the rise and fall of Empire, centuries' of humans evolving archived in the architecture of a city center. . . Too much of which has already been bulldozed and developed, so it is especially urgent that the country preserve what is left and rebuild what it can. This heritage reminds us that Albanians are not one thing – within Albanian culture and identity exist the rich histories of East and West, the best of many worlds preserved in one people.

But of course, you are Albanians — 700 years is nothing, the smallest drop in the vast expanse of time, from prehistory to the present day, that your ancestors have inhabited this land.[1] The Neolithic settlements recently discovered in Lin date back 8,000 years.[2] From prehistory through the rise of the Roman Empire, Albanian heritage chronicles the evolution of Europeans. Heritage workers, for example, are salivating at the recent excavations of Oricum, the missing piece for historians' analysis of Julius Caesar's campaign in the Great Roman Civil War.[3] In 49 BC, Caesar landed his troops at the Cove of Palasë— now, a World Bank Strategic investment that took environmentally protected land and turned it into the "Green Coast" — and marched his troops up Llogara Pass to launch a sneak land attack on Pompey's forces at Oricum.

Not long after Caesar emerged victorious, Roman conquest ravaged Albania; entire towns were razed, 150,000 Illyrians sold into slavery. And yet — and yet, Illyrians rose to become some of the most famous Emperors of Rome.[4] And here is precisely where cultural heritage shows us a way to heal wounds and restore the social fabric: cultural heritage illuminates the complexity of Albanian history and identity, a complexity that refuses simplistic categorizations. Great suffering over the years of Empire building exists side by side with an incredible resilience, an ability to overcome. Your heritage sites testify to many different lives, to many different times, and this complexity is what leads Mike Galaty - an archeologist whose work you may remember from the Shala Valley[5] - to say that Albanians have a unique place in the history of nation building. . . a place that offers important insights for our contemporary historical moment.

We are at an evolutionary cusp, when global warming forces us to re-evaluate the paths that have brought us to this precipice. While many Albanians too easily fall into the trap of thinking that their late arrival to modernity is a failure, Galaty sees Albanians' heritage as an asset to our species' evolving. All of our cultural forms are in the process of changing — the concrete and steel currently devouring our cities and turning the earth into an inhospitable planet are already obsolete. It is precisely Albania as a late-comer to these obsolete forms that makes it, paradoxically, an important mirror for re-imagining futures in which the human species might survive itself in this age of a changing climate.[6]

But, most immediately for the people and the country, recovering the positive value of Albanians' heritage can help to heal some of the most infected wounds debilitating the country — the wounds of communist persecution, on top of which are layered the traumas of transition and the normative abandonment that has made these wounds worse and perpetuated cycles of wounding.

The structure of state terror under the communist regime has never been fully documented, and no government has ever taken responsibility for the effects of state violence. I've written elsewhere about this, so here I will only say: the "enemy" other was the foundation upon which the entire structure of state violence was built. The enemy of the state, the enemy of the people — Every dissenting voice, every intellectual critique, every honest word spoken from a desire to right wrongs, to bring justice, to go beyond the limits of what "is" and imagine what can be — every single voice considered a challenge to the existing structures of power was defined as an enemy, exiled, interned, imprisoned, killed. The state got its power by turning Albanians against each other. This perverted the very fabric of social relations,

Layered on top of this foundational trauma are the traumas of transition — economic shock therapy, the gangs and Mafias to which this disastrous policy gave rise, and the oligarchs that grew out of these and now own the country — worse than owning the country, the oligarchs are bleeding the country to death.

Both of these traumas — the foundational trauma of state violence turning Albanians against each other and the traumas of transition — continue in relation to our failure to return to the wound of communist persecution, to clean it out and heal it. This is a third wound, the wound of normative abandonment. Normative abandonment is when the victims of a violence - here, with us, asking for what they have suffered to be recognized - are ignored, pushed aside, their suffering denied. This is a second violence, a violence even worse than the original trauma from which people suffered. Hundreds of people that I have interviewed about their time in the gulags here have confirmed this: worse than imprisonment, than starvation, than torture — even worse than the horrific things they suffered in the gulags — was being named an "enemy of the state" and shunned by their families, their neighbors, those they used to call their friends. It was, as many told me, like being dead — the walking dead, shunned, ostracized, outcast.

The wound of communist persecution, built on the creation of the other enemy, is so deep, so pervasive, that even the movement to save the national theater could not be protected from it. You will remember that, by the summer of 2020, the movement had split into three different factions. Inevitably — all wounds, unhealed, will eventually re-open.

BUT EVEN SO – even with these wounds still crippling the psyche of the country, the theater movement DID RISE to the level of national heroism. It was a profound accomplishment that, for over two years, citizens from every walk of life, from different social spheres, came together to stop illegal development and preserve the historic national theater. But beyond even this unprecedented and extraordinary accomplishment, when an earthquake devastated Albania on November 26, 2019, the national theater movement rose - and mobilized the country to rise - to provide aid to the victims. The citizens of Sheshi Teatri were the first responders, the trusted helpers to whom the country turned for inspiration, affirmation, assurance. It is not an exaggeration to call this national heroism.

The Albanians I know are not one thing – absolutely not simplistic, easily defined, not either this or that. They are both/and. Masters of adaptation AND stubborn — stubborn and unyielding. In some parts traumatized, in others joyfully alive. As a people, Albanians are not simply Muslim nor Catholic nor Orthodox, but all, everything. Recovering the positive value of cultural heritage allows Albanians to reconnect all of these gloriously different parts — reconnect, and love every part that the people have been throughout thousands of years of humans evolving. All of it — the beauty, the heroism, the resilience, as well as the pain, the suffering, the betrayals.

To recover this heritage, to preserve and restore it, to celebrate and to cherish it — these are acts of love. And love, in the end, is the only thing that will heal us.

We are at an evolutionary moment in history. Literally: on a planet already hotter than the disaster scenarios have been warned, our species, in order to survive, will have to evolve. Our cities of the future — as the heat wave ripping across Europe is demonstrating to us now — will demand different relationships to the land, to the environment, to energy. And this will require that WE evolve different relationships — collaborative relationships, compassionate relationships, loving relationships — to each other. As we re-imagine ourselves to imagine our futures, Albania's cultural heritage provides a portal into Europe's prehistoric past through which we can imagine new forms and relationships for our vibrant, thriving futures.

I pray that we will all rise to this challenge.

Love and light,

Lori

References:

[1] Galaty, Michael. 2018. Memory and Nation-Building: From Ancient Times to the Islamic State. Roman & Littlefield https://rowman.com/ISBN/9780759122604/Memory-and-Nation-Building-From-Ancient-Times-to-the-Islamic-State.

[2] Underwater investigations at Lin 3 (Lake Ohrid, Albania). EXPLO: Exploring the Dynamics and Causes of Prehistoric Land-Use change in the Cradle of European Farming. https://exploproject.eu/news/underwater-investigations-at-lin-3-lake-ohrid-albania/.

[3] The Ancient Port of Oricum: Albania 2017. Octopus Foundation. https://octopusfoundation.org/en/project/ancient-port-oricum-albania-2017-underwater-archaeology-history-caesar/.

[4] Lot, Ferdinand. 1996. The End of the Ancient World and the Beginnings of the Middle Ages. Routledge University Press https://www.routledge.com/The-End-of-the-Ancient-World/Lot/p/book/9780415868105.

[5] Galaty, Mike, Olse Lafe, Wayne E. Lee, and Zamir Tafilica, Eds. Light and Shadow: Isolation and Interaction in the Shala Valley of Northern Albania. 2013. UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archeology https://ioa.ucla.edu/press/light-and-shadow.

[6] For more on our evolutionary cusp, see: Fagan, Brian and Nadia Durant. 2021. Climate Chaos: Lessons on Survival from Our Ancestors. Public Affairs Books https://www.publicaffairsbooks.com/titles/brian-fagan/climate-chaos/9781541750883/.

Latest news

Second hearing on the protected areas law, Zhupa: Unconstitutional and dangerous

2025-06-30 22:18:46

Israel-Iran conflict, Bushati: Albanians should be concerned

2025-06-30 21:32:42

Fuga: Journalism in Albania today in severe crisis

2025-06-30 21:07:11

"There is no room for panic"/ Moore: Serbia does not dare to attack Kosovo!

2025-06-30 20:49:53

Temperatures above 40 degrees, France closes nuclear plants and schools

2025-06-30 20:28:42

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

2025-06-30 20:13:54

Turkey against the "Bektashi state" in Albania: Give up this idea!

2025-06-30 20:03:24

Accused of sexual abuse, producer Diddy awaits court decision

2025-06-30 19:40:44

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

2025-06-30 18:44:12

Tourism: new season, old problems

2025-06-30 18:27:23

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

2025-06-30 17:51:44

Almost free housing: East Germany against depopulation

2025-06-30 16:43:06

Hamas says nearly 60 people killed in Gaza as Trump calls for ceasefire

2025-06-30 16:14:15

Drownings on beaches/ Expert Softa: Negligence and incompetence by institutions!

2025-06-30 16:00:03

European ports are overloaded due to Trump tariffs

2025-06-30 15:30:44

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

2025-06-30 15:19:54

Lezha/ Police impose 3165 administrative measures, handcuff 19 drivers

2025-06-30 14:55:04

Young people leave Albania in search of a more sustainable future

2025-06-30 14:47:52

Record-breaking summer, health threats and preventive measures

2025-06-30 14:36:19

Constitution of the Parliament, Osmani invites political leaders to a meeting

2025-06-30 14:07:54

Heat wave 'invades' Europe, Spain records temperatures up to 46 degrees Celsius

2025-06-30 13:42:02

Accident in Vlora, car hits 2 tourists

2025-06-30 13:32:16

Kurti confirms participation in today's official dinner in Skopje

2025-06-30 13:03:27

Fight between 4 minors in Kosovo, one of them injured with a knife

2025-06-30 12:38:45

Report: Teenage girls the loneliest in the world

2025-06-30 12:20:40

Commissioner Kos and Balkan leaders meet in Skopje on Growth Plan

2025-06-30 12:07:59

Wanted by Italy, member of a criminal organization captured in Fier

2025-06-30 11:55:53

Hundreds of families displaced by wave of Israeli airstrikes in Gaza

2025-06-30 11:45:17

Zenel Beshi: The criminal who even 50 convictions won't move from Britain

2025-06-30 11:23:19

A new variant of Covid will circulate during the summer, here are the symptoms

2025-06-30 11:14:58

"Partizani" case, trial postponed to July 21 at the Special Court

2025-06-30 10:41:05

Uncontrolled desire to steal, what is kleptomania, why is it caused

2025-06-30 10:30:08

Requested change of security measure, hearing for Malltez postponed to July 7

2025-06-30 10:24:32

Output per working hour in Albania 35% lower than the regional average

2025-06-30 09:54:35

The trial for the "Partizani" file begins today

2025-06-30 09:27:57

22 fires in the last 24 hours in the country, 2 still active

2025-06-30 09:21:28

How is the media controlled? The 'Rama' case and government propaganda

2025-06-30 09:13:36

German top diplomat: Putin wants Ukraine to capitulate

2025-06-30 09:00:07

Foreign exchange, how much foreign currencies are sold and bought today

2025-06-30 08:44:38

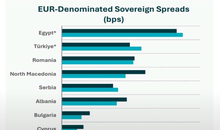

Chart/ Sovereign risk for Albania from international markets drops significantly

2025-06-30 08:26:38

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you?

2025-06-30 08:11:44

Clear weather and passing clouds, here is the forecast for this Monday

2025-06-30 07:59:32

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-30 07:47:37

Milan make official two departures in attack

2025-06-29 21:57:23

6 record tone

2025-06-29 21:30:46

4-year-old girl falls from balcony in Lezha, urgently taken to Trauma

2025-06-29 21:09:58

Assets worth 12 million euros seized from cocaine trafficking organization

2025-06-29 19:39:43

Fire in Durrës, Blushi: The state exists only on paper

2025-06-29 19:17:48

Fire endangers homes in Vlora, helicopter intervention begins

2025-06-29 18:27:51

France implements smoking ban on beaches and parks

2025-06-29 18:02:08

England U-21 beat Germany to become European champions

2025-06-29 17:42:49

Trump criticizes Israeli prosecutors over Netanyahu's corruption trial

2025-06-29 17:08:10

Street market in Durrës engulfed in flames

2025-06-29 16:52:57

UN nuclear chief: Iran could resume uranium enrichment within months

2025-06-29 16:03:24

Albanian man dies after falling from cliff while climbing mountain in Italy

2025-06-29 15:52:01

Another accident with a single-track vehicle in Tirana, a car hits a 17-year-old

2025-06-29 15:07:15

While bathing in the sea, a vacationer in Durrës dies

2025-06-29 14:54:01

Sentenced to life imprisonment, cell phone found in Laert Haxhiu's cell

2025-06-29 14:26:40

77 people detained in protest, Vučić warns of new arrests

2025-06-29 14:07:46