Flash News

Flash News

Drenova prison police officer arrested for bringing drugs and illegal items into cell

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

Serbian Persecution and Conversion in the Middle Ages: in the time of the Nemanjic Kingdom 'Catholic' meant 'Albanian'

This article is part of the "PRINT" section of Politiko.al, with materials taken from the funds of the Periodical and the Book of the National Library. Published in the newspaper "RD" dt. 25/04/1993, no. 349, p. 3.

by PËLLUMB XHUFI

In 'The Life of Stefan Nemanja', written by his son, the crowned Stephen, it is shown that around 1185 Nemanjd "united with his first homeland the whole province of Nis, Zvecan, Lipjan Morava, Vranje, the region of Prizren, the two Pologs and border areas with them ... defeating barbaric enemies with God's help. "The version of this life, written by Saint Sava adds that at the same time Stefan Nemanja expanded his conquests in Podrimje, Llap, Pult, and in the areas of the coastal Diocletian with the cities of Danja, Sarda, Drisht, Shkodra, Shas, Ulcinj of Bar. Various historical reports, from the quoted life of Stefan Nemanja to the repeated memoranda of the Popes of Rome, to the testimonies of Anonymous Gorka, Guljelm Admit or Spadugino on the expropriation and violent expulsion of generous Albanians, are transparent enough to see there a calculated effort aimed at transforming the Albanians into a raja people. As a result, at the beginning of the century. XIV almost all the lands of Kosovo, western Macedonia, and Zeta (Montenegro) were distributed to the feudal lords and especially to the Serbian monasteries that were erected here in a hurry.

But the Albanians were in the Serbian kingdom a powerful numerical reality and that is why they were then, no less than today a "destabilizing factor", to use a term of Bogdanovic, the Serbian avant-garde historian. Here begins a whole policy of failed Serbization, from the first of the Nemanjic in the century. XII until their end, Stefan Dushani. The most significant act of this policy proves to have been the violent conversion of Albanians to Serbian Orthodoxy. In terms of dimensions and consequences, this problem so far neglected by our historiography would deserve very special attention. The Serbian occupation of the 12th century found the Albanian populations of the northern and northeastern regions ecclesiastically linked to Byzantine Orthodoxy (Kosovo and Macedonia) and Roman Catholicism (Diokle-Zete). The last events of the century. XII related on the one hand to the southern expansion of the Serbian state and on the other hand to the deep crisis of the Byzantine Empire and the church of Constantinople, constitute the political background of the two phenomena observed at that time in the region we are interested in: on the one hand, we have the penetration of Catholicism from the coastal areas to the depths of the Albanian northeastern territories. In fact, starting from 1202, in addition to the traditional Catholic dioceses of Bar, Ulcinj, Shkodra, Danja, Drisht, the documents prove the same in Prizren, Skopje, Gjakova, Gracanica, Trepca, Novo Brdo, etc. Not only that, but special evidence, such as a diploma of Tsar Stefan Dushan in 1326, claims that the church and Catholic priests were also present in remote villages, which shows that Catholicism had turned in these areas into a massive phenomenon. The offensive of the church of Rome in the Orthodox east or the weakening of the church of Constantinople is not enough to explain the extent of such a phenomenon. The representation of the Catholic rite in these former domains of Byzantine Orthodoxy seems to have been more a form of reaction of the Albanians to the stifling pressure of the Serbian church, which in turn was pursuing a savage policy of conversion of the Catholic and Orthodox Albanians. in the Serbian national church. The special aspects of this policy are illuminated by a considerable amount of data coming from travelers, Catholic emissaries, the chancellors of the Popes, and the Serbian kings themselves. The conversion to the Serbian church was a priority direction of the Serbian state, and for this, it is enough to take a look at the code of Stefan Dusan, which in a way is the constitution of the medieval Serbian kingdom. The so-called "antiherpetic articles" of this code are unique in their severity. According to them, all citizens of the Serbian kingdom of a foreign community had to be baptized in the Serbian church. Catholics in particular, but also the Orthodox of the Byzantine rite, who refused to take such a step, were threatened with severe punishments, ranging from confiscation of property, expulsion, imprisonment, and stamping with a hot iron to the death penalty. The code in question sanctions the role of the Serbian king as the protector of the Serbian church and as the eradicator of "heresy". were threatened with severe punishments, ranging from confiscation of property, deportation, imprisonment, and stamping with a hot iron to the death penalty. The code in question sanctions the role of the Serbian king as the protector of the Serbian church and as the eradicator of "heresy". were threatened with severe punishments, ranging from confiscation of property, deportation, imprisonment, and stamping with a hot iron to the death penalty. The code in question sanctions the role of the Serbian king as the protector of the Serbian church and as the eradicator of "heresy".

It is understood that in such conditions, the problem goes beyond the simple religious framework. The "Catholic" frenzy of the Serbian kings is well understood as it is concluded that the geography of the Catholic rite in the kingdom of the Nemanjas corresponded almost completely with that of the Albanian ethnos. Still in the century. XVII Pjetër Bogdani claimed that in the areas of Montenegro, Kosovo, and Macedonia when the word "Catholic" was used, Albanians were meant. For Albanians to be rebaptized in the Serbian church would practically mean entering the process of merging them into the Serb community. Ecclesiastical assimilation, cultural assimilation, and ethnic assimilation were but a progressive stage of the same process of Serbization, which began precisely with the formal act of re-baptism and at the same time of receiving a new Slavic name.

However, the confrontation between the "schismatics" on the one hand and the "Latins" on the other, is constantly talked about in ecclesiastical and secular sources of the century. XII-XV is in fact a confrontation between Serbs and Albanians. The language, often dogmatic of medieval documentation, should not push us to lose historical perspective. The situation in the northern and northeastern Albanian areas under Serbian occupation has similar parallels to that of medieval Bohemia. It is well known that here, under the guise of religious conflict between the "Hussein heretics" and the "Catholic nobility" took place the war of the oppressed Czech people against the German feudal lords.

This combination of religious motive with the national one only explains the brutality with which the Serbian state tried to eradicate the "Catholic heresy" in the occupied Albanian lands.

As for the Catholic religion, in the territories where the Albanian ethnos confronted the Serbs, it became a kind of "refugium peccatorum" itself conservation and this explains the extraordinary success that Roman Catholicism achieved in the areas of Kosovo and Macedonia during the Serbian occupation. It is clear that embracing Catholicism in these areas was a matter of faith rather than a matter of political opportunity.

Embracing Catholicism, in addition to drawing a clear demarcation line between Albanians and Serbs, had another great advantage. He built a bridge between the Albanians and the Catholic powers of Europe, incorporating their resistance into the powerful "Serbian" coalition that took shape, especially at the beginning of the century. XIV who saw the Pope, Hungary, the Anjouan's of Naples, France engaged in the first person. Each of these powers had its own motives for clashing with the Nemanjic's Serbia, in their case it was a matter of territories and areas of influence. However, since the antagonist was the same for everyone, Serbia, these interests were sometimes channeled into really large joint ventures, such as the crusade of 1319. The documents of the time best illustrate the role played by the Albanians in these joint military actions. In 1332, after witnessing a powerful "Serbian" uprising of the generous Albanian Dhimitër Suma, the French missionary Guljelm Adami sent to the king of France the project of a new "Serbian" crusade. It is interesting to note that the author of the project in question considers it sufficient to send to Albania, from France only a symbolic contingent. Albanians, according to him, were able to face action against Serbs on their own. It is interesting to note that the author of the project in question considers it sufficient to send to Albania, from France only a symbolic contingent. Albanians, according to him, were able to face action against Serbs on their own. It is interesting to note that the author of the project in question considers it sufficient to send to Albania, from France only a symbolic contingent. Albanians, according to him, were able to face action against Serbs on their own.

The "internationalization" of the issue of Albanians in the Serbian kingdom, which owes to a large extent precisely their accession to the European Catholic front, opened a lot of trouble for the Serbian Nemanjic. These could not ignore the anathema and the Pope's constant pressure to end the oppression of Catholics in their domains. Behind these could come the armed ladders of Europe's sovereigns: the mobilization of the Crusades was at that time a real weapon in the hands of the Pope. So in many cases, the Serbian sovereigns responded to the pressures of Rome by promising to give up persecution against their Catholic citizens, a promise they certainly never kept. To make it even more credible, many of them, including the great persecutor Stefan Dushani, promised the Pope the abandonment of Serbian "schism" and conversion to the Catholic rite. There was even a Nemanja and this was Stefan Uroshi II, who to prove his devotion to the church of Rome asked Pope Nicholas IV to "fall" to the Bosnian heretics. This is a subtle way to occupy Bosnia without opposition, even with the approval of the Pope.

It must be said that such strategies did not remain ineffective at all. Although they were well aware that these were head-to-toe flowers ("simulatio completa") and that the Serbian kings were nothing but deceivers ("mendaces"), many popes were obsessed with the ecumenical idea wanted to hope for a conversion to the end. of the Serb Nemanjic and their people in the Catholic religion, which would also solve the problem of "Catholic" persecution in their kingdom. This strange but always present illusion in the papal religious book and in the courts of Catholic Europe.

Latest news

Second hearing on the protected areas law, Zhupa: Unconstitutional and dangerous

2025-06-30 22:18:46

Israel-Iran conflict, Bushati: Albanians should be concerned

2025-06-30 21:32:42

Fuga: Journalism in Albania today in severe crisis

2025-06-30 21:07:11

"There is no room for panic"/ Moore: Serbia does not dare to attack Kosovo!

2025-06-30 20:49:53

Temperatures above 40 degrees, France closes nuclear plants and schools

2025-06-30 20:28:42

Lavrov: NATO is risking self-destruction with new military budget

2025-06-30 20:13:54

Turkey against the "Bektashi state" in Albania: Give up this idea!

2025-06-30 20:03:24

Accused of sexual abuse, producer Diddy awaits court decision

2025-06-30 19:40:44

Kurti and Vučić "face off" tomorrow in Skopje

2025-06-30 18:44:12

Tourism: new season, old problems

2025-06-30 18:27:23

Construction worker dies after falling from scaffolding in Berat

2025-06-30 17:51:44

Almost free housing: East Germany against depopulation

2025-06-30 16:43:06

Hamas says nearly 60 people killed in Gaza as Trump calls for ceasefire

2025-06-30 16:14:15

Drownings on beaches/ Expert Softa: Negligence and incompetence by institutions!

2025-06-30 16:00:03

European ports are overloaded due to Trump tariffs

2025-06-30 15:30:44

The prosecution sends two Korça Municipality officials to trial

2025-06-30 15:19:54

Lezha/ Police impose 3165 administrative measures, handcuff 19 drivers

2025-06-30 14:55:04

Young people leave Albania in search of a more sustainable future

2025-06-30 14:47:52

Record-breaking summer, health threats and preventive measures

2025-06-30 14:36:19

Constitution of the Parliament, Osmani invites political leaders to a meeting

2025-06-30 14:07:54

Heat wave 'invades' Europe, Spain records temperatures up to 46 degrees Celsius

2025-06-30 13:42:02

Accident in Vlora, car hits 2 tourists

2025-06-30 13:32:16

Kurti confirms participation in today's official dinner in Skopje

2025-06-30 13:03:27

Fight between 4 minors in Kosovo, one of them injured with a knife

2025-06-30 12:38:45

Report: Teenage girls the loneliest in the world

2025-06-30 12:20:40

Commissioner Kos and Balkan leaders meet in Skopje on Growth Plan

2025-06-30 12:07:59

Wanted by Italy, member of a criminal organization captured in Fier

2025-06-30 11:55:53

Hundreds of families displaced by wave of Israeli airstrikes in Gaza

2025-06-30 11:45:17

Zenel Beshi: The criminal who even 50 convictions won't move from Britain

2025-06-30 11:23:19

A new variant of Covid will circulate during the summer, here are the symptoms

2025-06-30 11:14:58

"Partizani" case, trial postponed to July 21 at the Special Court

2025-06-30 10:41:05

Uncontrolled desire to steal, what is kleptomania, why is it caused

2025-06-30 10:30:08

Requested change of security measure, hearing for Malltez postponed to July 7

2025-06-30 10:24:32

Output per working hour in Albania 35% lower than the regional average

2025-06-30 09:54:35

The trial for the "Partizani" file begins today

2025-06-30 09:27:57

22 fires in the last 24 hours in the country, 2 still active

2025-06-30 09:21:28

How is the media controlled? The 'Rama' case and government propaganda

2025-06-30 09:13:36

German top diplomat: Putin wants Ukraine to capitulate

2025-06-30 09:00:07

Foreign exchange, how much foreign currencies are sold and bought today

2025-06-30 08:44:38

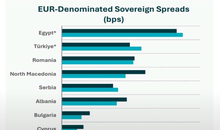

Chart/ Sovereign risk for Albania from international markets drops significantly

2025-06-30 08:26:38

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you?

2025-06-30 08:11:44

Clear weather and passing clouds, here is the forecast for this Monday

2025-06-30 07:59:32

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-30 07:47:37

Milan make official two departures in attack

2025-06-29 21:57:23

6 record tone

2025-06-29 21:30:46

4-year-old girl falls from balcony in Lezha, urgently taken to Trauma

2025-06-29 21:09:58

Assets worth 12 million euros seized from cocaine trafficking organization

2025-06-29 19:39:43

Fire in Durrës, Blushi: The state exists only on paper

2025-06-29 19:17:48

Fire endangers homes in Vlora, helicopter intervention begins

2025-06-29 18:27:51

France implements smoking ban on beaches and parks

2025-06-29 18:02:08

England U-21 beat Germany to become European champions

2025-06-29 17:42:49

Trump criticizes Israeli prosecutors over Netanyahu's corruption trial

2025-06-29 17:08:10

Street market in Durrës engulfed in flames

2025-06-29 16:52:57

UN nuclear chief: Iran could resume uranium enrichment within months

2025-06-29 16:03:24

Albanian man dies after falling from cliff while climbing mountain in Italy

2025-06-29 15:52:01

Another accident with a single-track vehicle in Tirana, a car hits a 17-year-old

2025-06-29 15:07:15

While bathing in the sea, a vacationer in Durrës dies

2025-06-29 14:54:01

Sentenced to life imprisonment, cell phone found in Laert Haxhiu's cell

2025-06-29 14:26:40

77 people detained in protest, Vučić warns of new arrests

2025-06-29 14:07:46