Flash News

Flash News

Video/ Iran's state television attacked 'live'

KPA upholds dismissal of Vlora prosecutor

Transporting illegal immigrants, 24-year-old arrested in Saranda

NAME/ Elderly man found dead inside a cave in Lezha

Murder of Chief Commissioner Artan Cuku, Tirana Court sentences two perpetrators to life imprisonment

Xhafer Lila lives in one of the buildings behind the Emin Duraku school in Tirana. He and a group of residents have been protesting for months after learning that a 16-story tower will be built in the space between the buildings and the school yard.

"I don't know how such a mess can be allowed, especially since it's next to a school where hundreds of students study, it's a real eye-opener for the children ," says an outraged Xhaferi, who has a close connection to the school as he is a teacher.

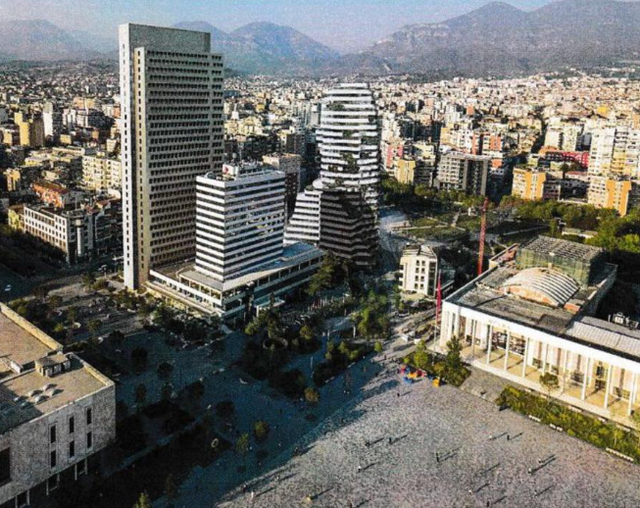

The tower that sparked residents' protest is not an isolated case, but a concrete example of a development model that is sweeping across Tirana.

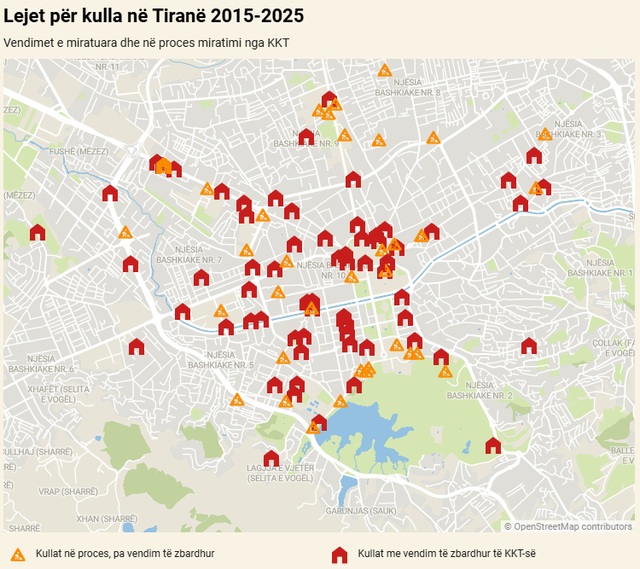

Citizens.al analyzed the permits reviewed by the National Council for Territory and Water (KKTU) and the Strategic Investment Committee (AIDA)* in the period 2015-2025, revealing that this collegial body has paved the way for the construction of at least 139 towers in the capital.

The KKTU is headed by Prime Minister Edi Rama, with extraordinary legal power, which he has regularly used to approve building permits that violate the criteria of the city's urban plan.

The Territorial Development Agency (TDA), which acts as the secretariat for the decisions of the KKTU, has in many cases failed to provide transparency in disclosing decisions on development and construction permits for towers, making public only 65 out of 139 decisions reviewed by the KKTU for buildings with heights from 8 to 100 floors.

There are a total of 72 projects that are only on the agenda of the KKT meetings, for which the institutions have ignored the duty to inform the public whether these constructions will be realized, rejected or changed.

Citizens.al has addressed the AZT with several requests for information, seeking transparency on the undisclosed decisions. The agency officially responded that the decisions are available on the AZT website, along with the site plan maps showing where the towers will be built.

To prove that this is untrue, it is enough to examine one of the last meetings of the KKTU, the one on February 27, 2025, where 59 construction and development permits were reviewed, of which only 9 were disclosed on the AZT website, while the other 50 remain non-transparent, in violation of the legal deadline of 90 days.

In another case, it took 8 months for the ARD to clarify the decision of the 33-story tower being built behind the National Theater.

"Towers rise, transparency decreases"

By analyzing permit data published over the last 15 years, Citizens.al has created a map of the location of towers in the capital. The data shows a progressive increase in height and intensity of construction.

Në përgjithësi, 139 kullat (65 me vendime të zbardhura) kanë një lartësi mesatare prej 26 katesh. Gjysma e këtyre objekteve shkojnë me lartësi nga 24 (mediana) deri në 100 kate.“Ajo që po ndodh është ‘kullëzim’ i qëndrës nën arsyetimin e rigjenerimit urban apo modernizimit,” thotë urbanistja Doriana Musai për Citizens. Ajo nënvizon se në asnjë kryeqytet europian nuk lejohet ndërtimi i 30-katëshëve pranë monumenteve të shek. XVIII–XIX.

Zonat më të prekura janë ato pranë Sahatit, ish-Teatrit Kombëtar, Bankës Kombëtare dhe stadiumit “Arena Kombëtare”, ku janë ndërtuar ose janë në proces projekte si “Eyes of Tirana”, “InterContinental Hotel Tirana”, “Mount Tirana”, “Book Building”, “Downtown One”, etj.

Në horizont, pas Operas, është shpallur projekti fitues për qiellgërvishtësin e parë që pritet të shkojë në 300 metra lartësi “Tirana Society Towers”.

Ekspertët argumentojnë se kjo është bërë e mundur përmes një përdorimi selektiv të Planit të Përgjithshëm Vendor (PPV) të kryeqytetit, që lejon “zonifikim të përzier” në shumë zona.

Zona e ish-Bllokut, është një shembull i qartë se si vendimet e KKTU-së kanë thyer kriteret e lartësisë dhe intensitetit të ndërtimit, të përcaktuara në planin urbanistik. Bashkia Tiranë parashikonte zhvillimin e zonës me godina nga 5 deri në 9 kate, ndërsa KKTU miratoi 12 lejet ndërtimi kullash me intensitet më të lartë.

Lartësia dominuese e ndërtimit në Tiranë ka ndryshuar sipas viteve, në periudhën 2000-2009, ndërtimi ishte kryesisht i kufizuar, me ndërtesa që rrallë e kalonin pragun e 10-kateve. Midis viteve 2010-2014, filloi të vërehej prirje drejt ndërtimeve më të larta, me objekte që shkonin deri në 15-kate, megjithatë me kufizime të qarta në zonat qendrore.

Ndryshimi i vërtetë ndodhi pas vitit 2015, kur Tirana përjetoi një “boom” kullash, me projekte që tejkalojnë 40-katet, duke përfshirë ndërtimet masive edhe në zona historike apo pranë monumenteve të mbrojtura.

KKTU: Më shumë fuqi, më pak kontroll dhe standarde

Që nga ndryshimet ligjore të vitit 2014, Këshilli Kombëtar i Territorit (KKT) është shndërruar në një instrument qendror të vendimmarrjes për zhvillimin urban në vend.

Ky organ ka marrë kompetenca të shtuara që kapërcejnë planifikimin urban tradicional dhe përfshijnë edhe administrimin e burimeve ujore – duke u emërtuar së fundmi si Këshilli Kombëtar i Territorit dhe Ujërave (KKTU).

Sipas urbanistes Doriana Musai, përbërja aktuale e KKTU-së – e dominuar nga ministra dhe përfaqësues të qeverisë – ka zëvendësuar modelin më të balancuar që ekzistonte më parë, duke dobësuar ndjeshëm mekanizmat e transparencës dhe kontrollit.

Përmes pesë ndryshimeve në Ligjin 107/2014 dhe dhjetë vendimeve të Këshillit të Ministrave, ky institucion ka përqendruar në mënyrë të pazakontë vendimmarrjen për ndërtimet strategjike, shpesh duke anashkaluar pushtetin vendor dhe institucionet mbikëqyrëse.

A significant example is the “Vertical Hour” project – a 41-story tower near the Sports University – which conflicts with the General Local Plan (PPV), which allows construction up to 9 floors.

The construction is planned on a public sports field, while the Municipality of Tirana changed the destination of the land with a decision in late 2023, paving the way for this development. This model has been opposed by architects, activists and citizens, raising concerns about cases of controversial expropriations that accompany similar projects.

Musai also points out the clash of current practices with the Law on Cultural Heritage (no. 27/2018), which stipulates that any intervention near monuments must receive a prior assessment by the relevant institutions. In reality, these assessments are often made “post-factum” – after the project has been politically approved – or are completely bypassed through special decisions of the National Council of Cultural Heritage justifying the construction as “national interest”.

She emphasizes that there is a lack of a functional monitoring system for the visual and aesthetic impact of towers in historic spaces./ Citizens.al

Latest news

KPA upholds dismissal of Vlora prosecutor

2025-06-16 17:16:43

The CEC begins the vote recount for four districts tomorrow

2025-06-16 17:08:19

Albanian Railways cuts 47 jobs, maintenance workers affected

2025-06-16 16:43:32

Foods to avoid after 40 for your health

2025-06-16 16:28:08

Albania stands by Israel: Iran must stop nuclear activity

2025-06-16 16:09:08

Two foreign citizens arrested in Dhërmi for selling narcotics

2025-06-16 16:07:54

Transporting illegal immigrants, 24-year-old arrested in Saranda

2025-06-16 15:42:05

NAME/ Elderly man found dead inside a cave in Lezha

2025-06-16 15:15:08

Britain appoints first woman to head intelligence service

2025-06-16 14:49:36

"Passive majority"/ Tabaku: SP has no political will to advance integration!

2025-06-16 14:12:34

Bardhi clashes with Spiropali: Close the Parliament to have lunch in Greece

2025-06-16 13:34:02

Accused of murder, Europol searching for Albanian criminal (NAME)

2025-06-16 13:06:17

"Karma finds its way", to whom is Veliaj's coded message from prison addressed?

2025-06-16 11:59:34

Tragic in Italy! Train hits and kills 19-year-old Italian-Albanian

2025-06-16 11:50:50

Map of towers: How the government is brutally rewriting Tirana

2025-06-16 11:37:09

Earthquake hits northern Macedonia, tremors felt in Albania

2025-06-16 11:00:48

Spahia: Two mandates in Shkodra were stolen from the DP

2025-06-16 10:31:58

"Partizani" file/ Berisha does not appear in SPAK for health reasons

2025-06-16 10:26:43

Belgian tourist injured in Gjipe, boat driver arrested

2025-06-16 10:01:03

NAME/ Drug dealer arrested in Vlora

2025-06-16 09:47:10

Attacks on Iran/DW: German policy in the Middle East under pressure!

2025-06-16 09:15:05

Von der Leyen: Iran must not have nuclear weapons

2025-06-16 09:06:17

Labor market alarm, Albanian workers' skills are 37% of those in the EU

2025-06-16 08:34:47

The Assembly meets in plenary session today, what is expected to be discussed

2025-06-16 08:25:30

35-year-old man shoots himself with a gun in Vlora, sent to 'Trauma'

2025-06-16 08:11:58

Mot i kthjellët në të gjithë vendin, ja parashikimi për këtë të hënë

2025-06-16 07:57:23

Posta e mëngjesit/ Me 2 rreshta: Çfarë pati rëndësi dje në Shqipëri

2025-06-16 07:44:49

Trump vetoes Israeli plan to assassinate Iran's supreme leader

2025-06-15 21:38:01

Vote recount in Tirana, Këlliçi: We want Alimehmet's mandate

2025-06-15 21:17:41

Erdogan calls Trump: We are ready to mediate for Iran

2025-06-15 20:55:34

Netanyahu says he attacked Iran to prevent 'nuclear holocaust'

2025-06-15 20:02:04

Migrant agreements: What benefits Kosovo and why are they criticized?

2025-06-15 19:43:08

Gjirokastër/ Fire burns three hectares of grass near the Kardhiqi Bridge

2025-06-15 19:22:34

Gattuso appointed new Italy national team coach

2025-06-15 18:34:17

Over 400 people have been killed so far in Israeli attacks on Iran

2025-06-15 18:15:47

Trump warns of return to Kosovo-Serbia issue: Biden damaged it

2025-06-15 17:46:52

Bylykbashi: Current electoral system is toxic

2025-06-15 17:25:20

Trump vows for Iran-Israel deal, mentions Kosovo case with Serbia

2025-06-15 16:59:02

German tourist injured on Gjipesa beach, hit by a dinghy's propeller

2025-06-15 16:40:31

Iran attacks Israel with ballistic missiles

2025-06-15 15:48:49

Fecal beach in Durrës, the other side of the tourist miracle

2025-06-15 15:30:57

The attempt to constitute the Assembly in Kosovo fails again

2025-06-15 14:59:10

Ish-presidentit francez Sarkozy i hiqet medalja e Legjionit të Nderit

2025-06-15 14:58:46

Shkodra, with the highest population contraction after the Census

2025-06-15 14:31:47

Caused a fatal accident and left the scene, 35-year-old arrested in Lezha

2025-06-15 13:40:10

Rare! Whale appears near the Karaburun peninsula

2025-06-15 12:42:49

Stranded at sea, Border Police brings 8 foreign citizens ashore

2025-06-15 12:05:01

Who were the four Iranian generals killed in the Israeli attack?

2025-06-15 11:43:36

Simon Zereci is appointed head of the Republic Guard

2025-06-15 11:10:36

Gennaro Gattuso is expected to be the new Italy coach

2025-06-15 10:45:46

Two vehicles collide in Korça, one injured

2025-06-15 10:20:28

Trump says US can easily broker deal between Iran and Israel

2025-06-15 10:06:11

Italy/ 45-year-old Albanian woman stabbed to death by ex-husband

2025-06-15 09:16:43

Foreign exchange, the rate at which foreign currencies are sold and bought

2025-06-15 09:03:57

Horoscope, what do the stars have in store for you today?

2025-06-15 08:50:41

Albania risks falling below 2 million inhabitants before 2035

2025-06-15 08:30:11

Temperatures reach up to 32 degrees Celsius, weather forecast

2025-06-15 08:18:49

Morning Post/ In 2 lines: What mattered yesterday in Albania

2025-06-15 08:00:49

Two vehicles collide in Karbunara, one injured

2025-06-14 21:36:38

A person is found without signs of life in Peja

2025-06-14 21:18:19